Pregnant women with acute respiratory distress syndrome triggered by COVID-19

MAIN FINDINGS

Ten out of thirteen pregnant women admitted to Rikshospitalet's intensive care units with acute respiratory failure triggered by COVID-19 were intubated after therapeutic failure with non-invasive mechanical ventilation.

All patients met criteria for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

All patients survived hospitalisation, but there were two cases of intrauterine fetal demise.

Almost half of the patients reported moderate to severely reduced self-perceived health and quality of life 15 months after discharge from intensive care.

Acute respiratory failure is a common cause of admission to an ICU in patients with COVID-19. In Norway, mortality among critically ill COVID-19 patients has been moderate (1), but survivors face an increased risk of late complications, known as post-intensive care syndrome. This particularly applies to patients who develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) during the course of their illness (2).

In pregnancy, ARDS as a complication of COVID-19 is life-threatening for both the mother and the fetus (3). This report describes the characteristics, treatment and clinical courses of pregnant women referred to Rikshospitalet due to ARDS triggered by COVID-19.

Material and method

Pregnant women with COVID-19 were registered on admission to an ICU at Rikshospitalet, Oslo University Hospital in the period March 2020 to May 2023. Rikshospitalet does not have a dedicated national facility for the comprehensive treatment of critically ill pregnant women, but in collaboration with other hospitals has accepted patients where the risk to the mother and fetus has been deemed particularly high and where evaluation for management with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is pertinent. We reviewed the patients' medical records retrospectively and describe clinical trajectories, management parameters and laboratory data collected during the period in intensive care.

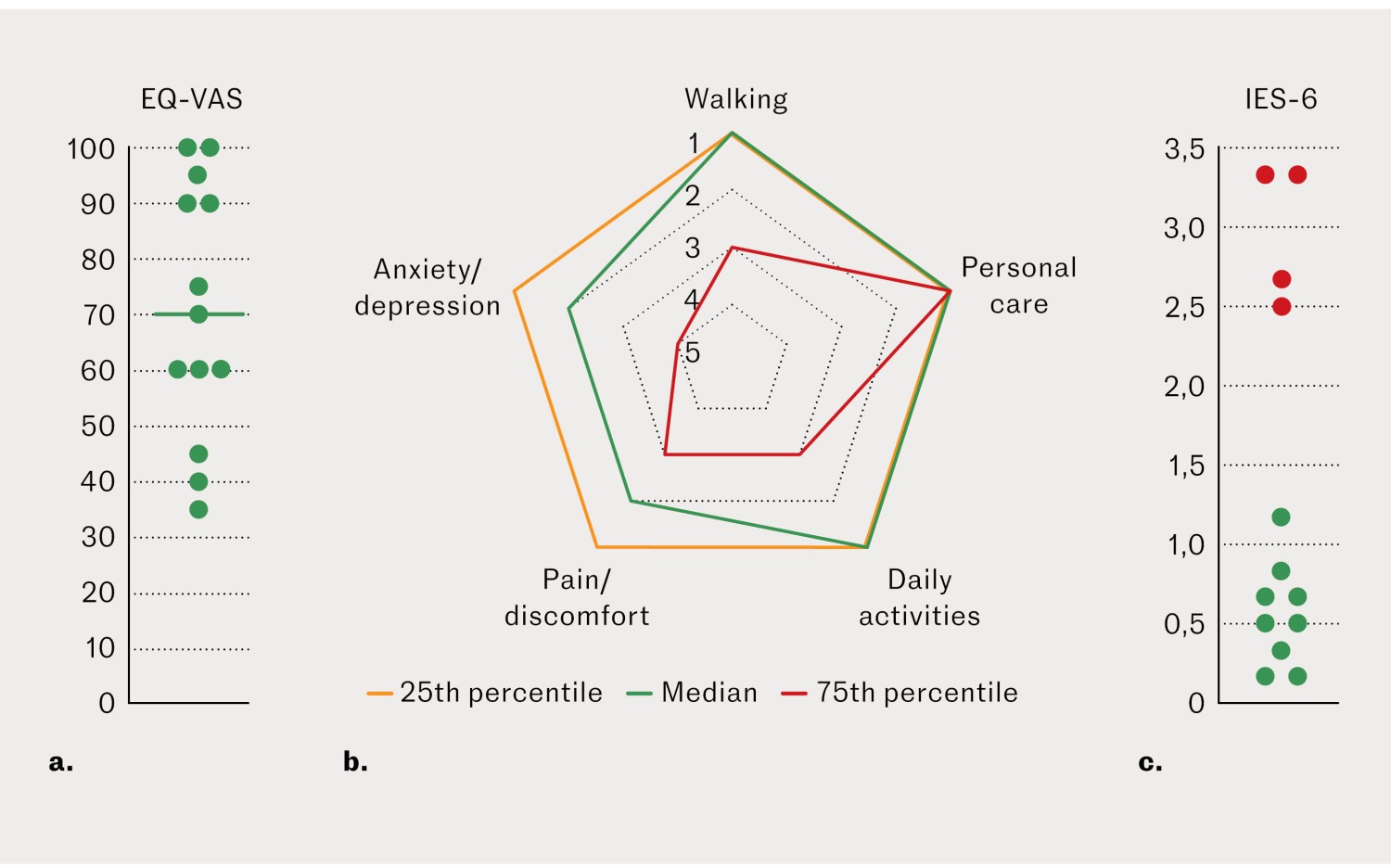

Fifteen months after discharge, the patients were asked about self-perceived health, quality of life and symptoms of post-traumatic stress. The Euro Quality of Life – Five Dimensions – Five Levels (EQ-5D-5L) and Impact of Event Scale-6 (IES-6) screening tools were employed for this purpose (4, 5). Mean or median values are presented, with measures of dispersion indicated as minimum and maximum values unless otherwise specified. The analysis was conducted using Stata version 17.0 and Microsoft Excel.

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) South-East (REK number 630377) and the data protection officer at Oslo University Hospital. All patients provided informed consent.

Results

Thirteen pregnant women with ARDS triggered by COVID-19 were admitted to an ICU at Rikshospitalet in the period February to December 2021. None of the women were vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 before hospitalisation. Ten women had an immigrant background (6). The duration of illness before admission varied from one to eleven days after symptom onset. All patients met criteria for ARDS, with little comorbidity (Table 1).

Table 1

Patient and management characteristics in 13 pregnant women with ARDS triggered by COVID-19 and admitted to an ICU at Rikshospitalet, Oslo University Hospital in the period March 2020 to May 2023. Values are presented as median (min. – max.) unless otherwise specified.

| Patient and management characteristics | Values | Reference values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33 (22–42) | - | |

| Weight at admission (kg) | 74 (60–96) | - | |

| Height (cm) | 161 (150–170) | - | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 (24–37) | - | |

| Parity | 1 (0–3) | - | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 27 (24–35) | - | |

| Comorbidity (n) | - | ||

| Musculoskeletal problems | 5 | - | |

| Mental health issues | 4 | - | |

| Endocrine disease | 4 | - | |

| Other | 3 | - | |

| SAPS II score1 | 38 (21–70) | - | |

| Laboratory findings at admission | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.7 (8.1–11.9) | 11.7–15.3 | |

| Leukocytes (× 109/L) | 8.0 (6.1–18.3) | 3.5–10 | |

| Neutrophils (× 109/L) | 6.9 (5.1–16.5) | 1.5–7.3 | |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 231 (155–312) | 145–390 | |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 1.2 (0.5–10) | < 0.50 | |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 4.7 (3.1–6.3) | 1.9–4.0 | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 353 (241–562) | 105–205 | |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | 126 (42–825) | 10–170 | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 74 (38–166) | < 4 | |

| Procalcitonin (µg/L) | 0.2 (0.0–1.0) | < 0.10 | |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 36 (26–71) | 45–90 | |

| Bilirubin (µmol/L) | 8 (4–26) | 5–25 | |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation (SaO2) (%) | 96 (88–100) | 97–100 | |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) | 0.5–2.3 | |

| Management data | |||

| Length of hospital stay (no. of days) | 16 (10–83) | - | |

| Length of stay in ICU (no. of days) | 8 (4–35) | - | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (no. of days; n = 10) | 8 (1–25) | - | |

| Non-invasive respiratory support (no. of days; n = 13) | 1 (0–2) | - | |

| P/F ratio2 (kPa; n = 10) (at admission) | 14 (9–36) | > 50 | |

| Highest peak pressure (cm H2O; n = 10) | 29 (23–32) | - | |

| PEEP (cm H2O; n = 10) | 11 (8–15) | - | |

| Tidal volume (mL/kg predicted body weight (PBW); n = 10) | 6.1 (2.5–7.4) | - | |

1SAPS II = simplified acute physiology score, 2nd edition. Sigmoid scale of 0–150 points, where 38 points (median) corresponds to an expected hospital mortality rate of approximately 20%, 21 points corresponds to a hospital mortality rate of approximately 5%, 70 points corresponds to a hospital mortality rate of approximately 80%.

2P/F ratio = the ratio between the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2), expressed in kilopascals, and the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2). PBW, predicted body weight (45.5 + (0.91 x [height in centimetres – 152.4])).

Ten patients were orally intubated after therapeutic failure with non-invasive mechanical ventilation. All intubated patients were managed with volume- and pressure-limited ventilation (Table 1). Five patients were managed in a modified prone position. Nine patients were given neuromuscular blocking agents and all received corticosteroids.

In the case of a previously healthy woman in her late twenties, venovenous ECMO treatment was deemed necessary following unsuccessful management with conventional lung-protective mechanical ventilation with deep sedation, neuromuscular blocking agents, prone positioning and nitrogen monoxide. ECMO could be discontinued after 17 days and the patient was extubated after a total of 25 days of invasive mechanical ventilation. She delivered the child by caesarean section five weeks before the estimated due date.

The median length of stay in ICUs at Rikshospitalet was eight days (Table 1). All patients had single-organ failure. Two patients experienced acute complications: pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax requiring no treatment. Seven intubated patients were found to have co-infections, which were treated with antibiotics.

The pregnancy

Upon admission to Rikshospitalet, the patients were in the second or third trimester of pregnancy (Table 1). There was no evidence to suggest that delivery would improve the women's prognosis. In most cases, continuation of pregnancy was considered necessary to avoid severe prematurity and to ensure fetal lung maturation with a two-day course of steroids. All patients were monitored with daily cardiotocography (CTG) and/or ultrasound examination. Emergency plans, including infection control measures, were established to deal with potential cases of perimortem caesarean section.

Three women on mechanical ventilation delivered by caesarean section due to an increasing need for oxygen, repeated episodes of desaturation and haemodynamic instability. Two women had a vaginal delivery following intrauterine fetal demise. In these two cases, placental histopathological examination revealed subacute placentitis and maternal vascular malperfusion.

Self-reported health and quality of life

The median value for self-rated health (EQ-VAS) was 70 (35–100) (Figure 1a). Patients reported minimal issues related to personal care, while pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression were prominent (Figure 1b). Symptoms of post-traumatic stress were most common in women with pre-existing mental health issues (Figure 1c).

Discussion

Pregnant women with COVID-19 are believed to be at increased risk of developing a severe clinical course, especially if infected with specific virus variants (Delta) (7). In Norway, however, all pregnant women with COVID-19 admitted to an ICU have survived hospitalisation (n = 30, unpublished data from the Norwegian Intensive Care and Pandemic Registry) (8). One of the guiding principles in obstetrics is that seriously ill pregnant women are assessed for critical care on a par with non-pregnant women. However, balancing the decision between prolonging the pregnancy to mitigate extreme prematurity and contemplating the option of delivery or pregnancy termination to enhance maternal care is a complex challenge. Recent international data support our decision to continue our patients' pregnancies (9).

None of the women in our study were vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 before hospitalisation. At the start of the Norwegian vaccination programme in December 2020, vaccination was not recommended for pregnant women. It was not until January 2022 that the vaccine was extended to all pregnant women irrespective of gestational age (10). The changing guidance on vaccination, lack of targeted information and concerns among pregnant women about potential adverse effects may all have contributed to pregnant women's reluctance to be vaccinated, even after amendments to the vaccine recommendations. Factors such as immigrant background, language barriers and cultural differences may also have impacted attitudes to vaccination in our patient population.

The patients in our study primarily had acute respiratory failure with little extrapulmonary organ dysfunction (Table 1). Most experienced therapeutic failure with non-invasive mechanical ventilation and required endotracheal intubation. Mechanical ventilation is a mainstay in the management of ARDS and gentle ventilation is needed to avoid further lung injury (11). A strong recommendation has been made for the use of corticosteroids (dexamethasone) to treat ARDS triggered by COVID-19 (12). However, dexamethasone crosses the placenta, and WHO recommends switching to equipotent doses of prednisolone or methylprednisolone after a maximum of two days. This also preserves the effect of dexamethasone with respect to fetal lung maturation.

ECMO in pregnant women is associated with a risk of serious complications (13) that must be weighed against the risk of continued conventional ventilation. As we had no prior experience with venovenous ECMO in pregnant women with ARDS, we contacted colleagues at the University of Michigan and the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) to broaden our understanding. Reassuringly, we received confirmation that our standard procedures are applicable to pregnant women as well.

Long-term follow-up of intensive care patients is recommended to identify symptoms of post-intensive care syndrome (2). While ICU admissions are often related to physical issues, our study highlights the significance of mental and cognitive health problems. Fifteen months after discharge from the ICU, patients were not struggling with daily activities to any significant extent. Nevertheless, almost half reported non-specific pain, discomfort, anxiety or depression, and one in three were experiencing post-traumatic stress. Notably, post-traumatic stress was more prevalent in patients with pre-existing mental health issues. The median value for self-perceived health in our study was comparable with findings in other studies of former intensive care patients, while the proportion with symptoms of post-traumatic stress was slightly higher (14).

Summary

Thirteen pregnant women were admitted to ICUs at Rikshospitalet with ARDS triggered by COVID-19. All patients were discharged alive, but there were two cases of intrauterine fetal demise. Adherence to current guidelines for gentle mechanical ventilation was central to our approach. Just under half of the patients reported a reduced quality of life 15 months after discharge from intensive care, attributed to non-specific pain and discomfort, anxiety and depression, as well as symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Laake JH, Buanes EA, Småstuen MC et al. Characteristics, management and survival of ICU patients with coronavirus disease-19 in Norway, March-June 2020. A prospective observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2021; 65: 618–28. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

Herridge MS, Azoulay É. Outcomes after Critical Illness. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 913–24. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Lim MJ, Lakshminrusimha S, Hedriana H et al. Pregnancy and Severe ARDS with COVID-19: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Outcomes and Treatment. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2023; 28. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2023.101426. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 1727–36. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Hosey MM, Leoutsakos JS, Li X et al. Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in ARDS survivors: validation of the Impact of Event Scale-6 (IES-6). Crit Care 2019; 23: 276. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

SSB. Slik definerer SSB innvandrere. https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/innvandrere/artikler/slik-definerer-ssb-innvandrere Accessed 1.12.2023.

- 7.

French and Swiss COVI-PREG group. Maternal and perinatal outcomes following pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants infection among unvaccinated pregnant women in France and Switzerland: a prospective cohort study using the COVI-PREG registry. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2023; 26. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100569. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Helse Bergen. Norsk pandemiregister. https://www.helse-bergen.no/norsk-pandemiregister Accessed 1.12.2023.

- 9.

Vasquez DN, Giannoni R, Salvatierra A et al. Ventilatory Parameters in Obstetric Patients With COVID-19 and Impact of Delivery: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Chest 2023; 163: 554–66. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Folkehelseinstituttet. Råd og informasjon for gravide og ammende. https://www.fhi.no/ss/korona/koronavirus/coronavirus/befolkningen/rad-for-gravide-og-ammende/?term= Accessed 7.12.2023.

- 11.

Scandinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Scandinavian clinical practice guideline on mechanical ventilation in adults with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015; 59: 286–97. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

WHO. Therapeutics and COVID-19: living guideline. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-therapeutics-2022.4 Accessed 7.12.2023.

- 13.

Byrne JJ, Shamshirsaz AA, Cahill AG et al. Outcomes Following Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe COVID-19 in Pregnancy or Post Partum. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.14678. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Fjone KS, Buanes EA, Småstuen MC et al. Post-traumatic stress symptoms six months after ICU admission with COVID-19: Prospective observational study. J Clin Nurs 2024; 33: 103–14. [PubMed][CrossRef]

Aslam og kolleger deler viktige erfaringer ved behandling av alvorlig syke gravide med covid-19 i Norge i Tidsskriftet, men feilrapporterer rådene om koronavaksine til gravide i Norge.

Folkehelseinstituttet (FHI) fulgte nøye med på kunnskapen om alvorlig sykdom hos gravide fra starten av koronapandemien, og Medisinsk Fødselsregister etablerte utvidet rapportering om gravide innlagt på sykehus med covid-19. På tross av klare internasjonale anbefalinger ble gravide ekskludert fra utprøvingsstudiene for koronavaksinene (1). Land som USA og Storbritannia tilbød likevel gravide vaksine på grunn av høye smittetall og mange gravide med alvorlig sykdom, og dannet dermed kunnskapsgrunnlaget for andre lands råd (2-4).

Det var få gravide med alvorlig koronasykdom i Norge i 2020 og første halvår av 2021 i Norge (5). FHI anbefalte i januar 2021 at vaksinasjon kunne overveies for gravide med risikotilstander, og i mai også for gravide i områder med høy smittespredning. I august 2021 ble alle gravide ble anbefalt vaksine (6). På dette tidspunktet var kunnskapsgrunnlaget for sikkerheten ved vaksinasjon for mor og det ufødte barnet bedret, og andre land rapporterte samtidig om flere tilfeller av alvorlig sykdom blant gravide med deltavarianten (7). FHI hadde tett dialog og samarbeid med nasjonale fagmiljøer både før og etter at anbefalingen ble offentliggjort.

Vaksinasjonsdekningen økte raskt, og andelen fødende kvinner som hadde fått minst én vaksinedose i svangerskapet steg fra 27% i september 2021 til 70% i januar 2022 (8). Dette tyder på at norske gravide fulgte anbefalingen i stor grad. Vaksinasjonsdekningen var lavere blant enkelte innvandrergrupper, inkludert gravide blant disse. FHI jobbet målrettet med å bedre informasjonen til innvandrere generelt og gravide innvandrere spesielt. I desember 2021 ble oppfriskningsdose anbefalt til alle gravide, og gjeldende anbefaling er at alle gravide bør ta én dose av koronavaksine i 2. eller 3.trimester av svangerskapet (9).

Aslam og kolleger bekrefter at uvaksinerte gravide er utsatt for alvorlig covid-19 sykdom også i Norge, og at fortløpende overvåking av sykdomsbyrde og vaksinasjonsdekning blant gravide er viktig for å kunne målrette tiltak. FHI anbefaler både influensa- og koronavaksine til alle for å beskytte mor og barn mot alvorlig sykdom, og vil fortsette å arbeide for å nå ut med et likeverdig vaksinasjonstilbud til alle gravide.

Litteratur:

1. Heath PT, Doare KL, Khalil A. Inclusion of pregnant women in COVID-19 vaccine development. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 9: 1007-8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30638-1.

2. Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR et al. Preliminary Findings of mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine Safety in Pregnant Persons. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 2273-82. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104983

3. Riley LE. mRNA Covid-19 Vaccines in Pregnant Women. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 2342-3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2107070

4. GOV.UK. Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation: advice on priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination, 30 December 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/priority-groups-for-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-advice-from-the-jcvi-30-december-2020/joint-committee-on-vaccination-and-immunisation-advice-on-priority-groups-for-covid-19-vaccination-30-december-2020 Lest: 7.3.2024

5. Varpula R, Äyräs O, Aabakke AJM et al. Early suppression policies protected pregnant women from COVID-19 in 2020: A population-based surveillance from the Nordic countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. DOI: 10.1111/aogs.14808

6. FHI. Covid-19 vaksinasjonsprogrammet, Vaksinasjon av gravide. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/3596efb4a1064c9f9c7c9e3f68ec481f/2021-08-18-vaksinasjon-av-gravide.pdf Lest 7.3.2024

7. Vousden N, Ramakrishnan R, Bunch K et al. Severity of maternal infection and perinatal outcomes during periods of SARS-CoV-2 wildtype, alpha, and delta variant dominance in the UK: prospective cohort study. BMJ Medicine 2022; 1. doi: 10.1136/bmjmed-2021-000053

8. Örtqvist AK, Dahlqwist E, Magnus MC et al. COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant women in Sweden and Norway. Vaccine 2022; 40: 4686-92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.083.

9. FHI. Covid-19 vaksinasjonsprogrammet, Delsvar på Oppdrag 49 – Vurdering av oppfriskningsdose til aldersgruppen 18-44 år. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/3596efb4a1064c9f9c7c9e3f68ec481f/delsvar-pa-oppdrag-49---vurdering-av-oppfriskningsdose-til-aldersgruppen-18-44-ar.pdf Lest: 7.3.2024

I vår artikkel om gravide med kritisk sykdom utløst av Covid-19 (1) har vi påpekt at ingen av våre pasienter var vaksinert og vi har diskutert mulige forklaringer. Om Folkehelseinstituttets (FHI) vaksineråd skriver vi følgende: «Vaksine til gravide var ikke anbefalt ved oppstart av vaksineprogrammet i desember 2020, og først i januar 2022 fikk alle gravide kvinner tilbud om vaksine uavhengig av svangerskapets varighet.»

Vi har hentet våre opplysninger fra FHIs nettside «Råd og informasjon for gravide og ammende» (2). Denne inneholder aktuelle vaksineråd, og nederst på nettsiden finnes en «endringshistorikk» hvor følgende er angitt: «29.04.2021: Oppdatert tekst ut fra ny kunnskap. Endret råd om vaksinering av gravide til at det kan overveies hvis fordelene overgår ulempene, også for gravide i områder med høy smittespredning og som ikke har andre underliggende sykdommer.» «31.01.2022: Endret anbefaling til å gjelde alle gravide uavhengig av trimester.»

Greve-Isdahl og medforfattere hevder i sin kommentar at «I august 2021 ble alle gravide ble anbefalt vaksine.» Men i dokumentet fra august 2021, som det vises til, står det følgende: «Alle gravide bør tilbys vaksine mot Covid-19. [..] Vaksine anbefales i 2. og 3. trimester med mindre det er risikofaktorer hos mor eller stor smitterisiko som tilsier vaksinasjon i 1. trimester.» (3) Her er det altså lagt inn et forbehold om vaksinetidspunkt som noen vil oppfatte som begrensende, og så kan man diskutere hvordan ord som tilbys og anbefales oppfattes i befolkningsgrupper med svake språkkunnskaper.

Våre kollegaer på FHI bekrefter at så mange som 30% av alle gravide fortsatt ikke var vaksinert i januar 2022, altså over ett år etter starten på vaksineprogrammet. Vi synes kanskje det bør påkalle FHIs interesse i større grad enn våre formuleringer.

Litteratur:

1. Aslam TN, Barratt-Due A, Fiane AE et al. Gravide med akutt, alvorlig respirasjonssvikt utløst av covid-19. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2024; 144. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.23.0615

2. Folkehelseinstituttet. Råd og informasjon for gravide og ammende. https://www.fhi.no/ss/korona/koronavirus/coronavirus/befolkningen/rad-for-gravide-og-ammende/?term= Lest 11.3.2024.

3. Folkehelseinstituttet. Covid-19 vaksinasjonsprogrammet. Vaksinasjon av gravide. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/3596efb4a1064c9f9c7c9e3f68ec481f/2021-08-18-vaksinasjon-av-gravide.pdf Lest 11.3.2024.