Main findings

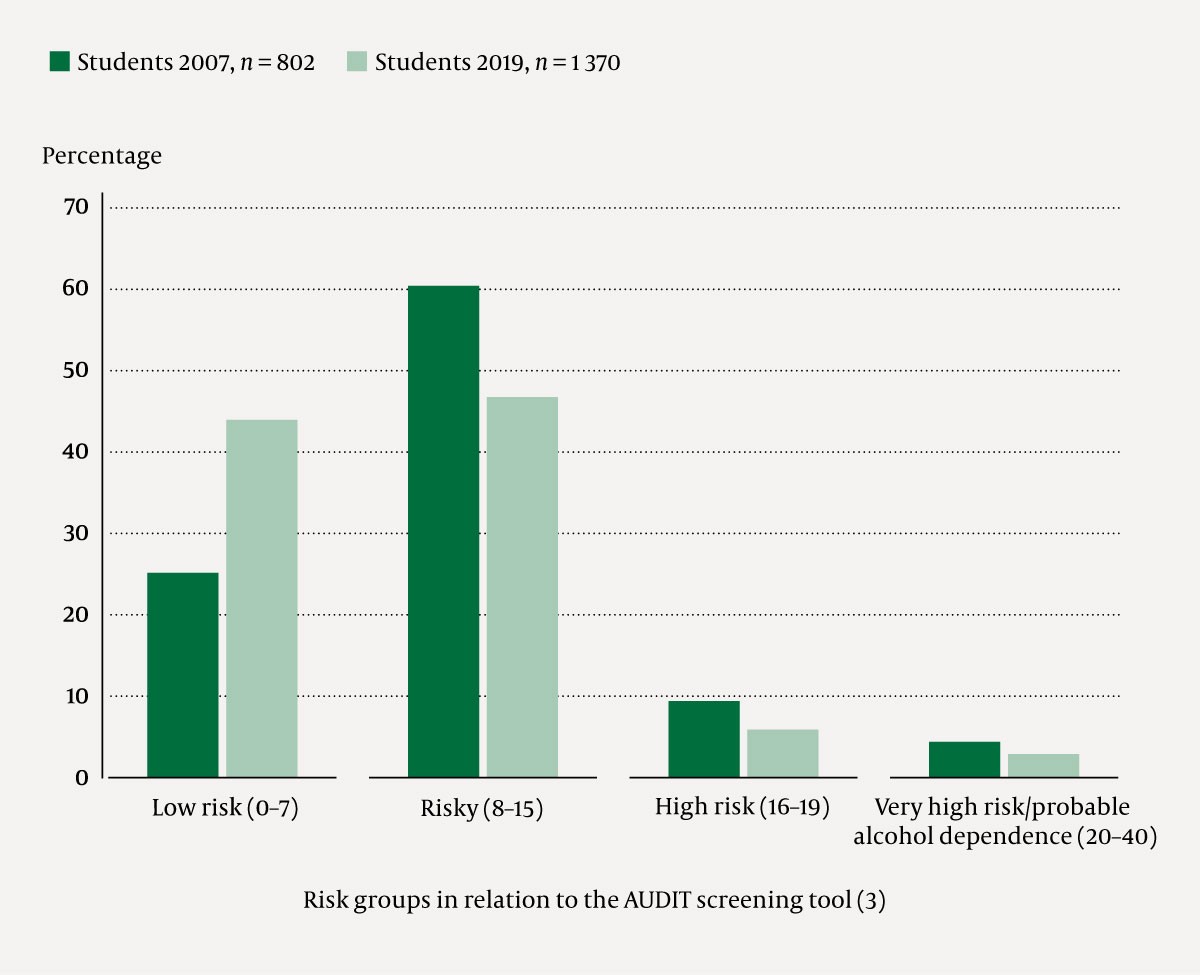

The proportion of NTNU students with risky/potentially harmful alcohol use decreased by 18.8 % from 2007 to 2019.

Among students in 2019, 67.8 % consumed a quantity of alcohol on a typical drinking day that corresponds to binge drinking, which is a reduction of 12.8 % compared to 2007.

In 2019, 55.9 % of students faced a potential long-term risk due to their alcohol consumption.

Alcohol consumption is a major challenge for global public health and a risk factor for years of healthy life lost (1, 2). Harmful alcohol use is defined as alcohol consumption that leads to health and social consequences, while risky alcohol use is defined as a drinking pattern that increases the risk of such consequences to an extent that necessitates involvement and advice from healthcare personnel (3, 4). Norwegians' drinking habits vary with age and sex. The tendency is for older people to spread their alcohol intake over several episodes, while younger people drink less frequently but consume more units of alcohol each time. On average, men drink a greater amount and more frequently than women (5).

The student environment is a subculture in which alcohol consumption seems to be tolerated and facilitated to a greater extent than in the rest of society (6). Buddy weeks, festivals and a flexible timetable enable alcohol habits to be formed that are otherwise difficult to maintain in a daily life with work and family obligations. Starting higher education is associated with increased alcohol consumption (7). A study of students in Bergen found an association between increasing alcohol consumption and students who were single, male, childless, non-religious, extroverted or unconscientious (8).

The students' alcohol use is largely characterised by frequent episodes of binge drinking (9). Binge drinking is defined as drinking five or more units of alcohol for men and four or more units for women on the same occasion (10). Several scientific articles use the definition of five or more units on the same occasion for both sexes (8, 11, 12). In 2018, a national student survey showed that the total alcohol consumption of 57 % of students in Norway was equivalent to binge drinking (13), and a survey in 2022 reported similar findings (14). Studies have shown that frequent binge drinking increases the risk of negative alcohol-related consequences, including injuries, alcohol-induced amnesia, physical violence, sexual assault and health problems, or death as a result of injuries. Frequent binge drinking can also lead to reduced academic performance (15).

Student surveys indicate that the alcohol use of 44–53 % of students in Norway is classified as risky and potentially harmful (8, 13). The corresponding figure for the general population during the same period was 15 % (5). The objective of this study was to examine alcohol use trends among students at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in a twelve-year perspective.

Method

The study is cross-sectional and is based on data from two questionnaire surveys conducted at NTNU in 2007 and 2019. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Three inclusion criteria were used: student status, having studied for a minimum of 0.5 years, and having studied for a maximum of 10 years.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of 41 questions: 26 compulsory questions for all students and 15 additional questions. It mainly consisted of predefined response alternatives, with certain sections allowing respondents to provide further details using free text. The questionnaire took approximately 10 minutes to complete and included background variables such as sex, age and number of years as a student, in addition to 13 questions about alcohol use. To standardise the self-reporting, one unit of alcohol was defined at the start of the questionnaire. Additional questions about geographical origin and faculty affiliation were included in the 2019 survey. In order to maintain the basis for comparison, none of the original questions were changed. A complete overview of the questionnaires can be found in Appendix 1 (in Norwegian only).

Alcohol use was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), which maps alcohol intake, dependence symptoms and alcohol-related problems. Respondents are categorised into different risk levels based on their score: low risk (< 8), risky/potentially harmful (8–15), high risk/harmful (16–19) and very high risk/probable alcohol dependence (20–40) (3). An AUDIT score ≥ 8 is the most widely used and best-validated threshold value between low-risk and risky/potentially harmful alcohol use (3, 16).

Data collection

The data were collected in spring 2007 and autumn 2019. The data collection and processing methods were the same in both surveys. The surveys were conducted during breaks from well-attended lectures at NTNU at various times of the day. Students were recruited from all faculties at NTNU in Trondheim. Oral and written information about the study was provided, and students had the option to either complete the questionnaire in the lecture hall or at a later time. Completed questionnaires were submitted anonymously in a post box situated in the auditorium or by post. After submission, the questionnaires were scanned using the TeleForm program (OpenText, v20.3). Information that the program had difficulty interpreting was verified manually.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (IBM, v29). Background variables were described descriptively, with frequencies and percentages or mean and standard deviation (SD). Descriptive statistics and significance testing were used to analyse alcohol use, including sex-based differences. Statistical testing encompassed independent t-tests, chi-square tests and the Mantel-Haenszel test for trend. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. Where a question had not been answered, the respondent was only excluded from the analysis of the variable in question. For the calculation of AUDIT scores, all relevant questions had to be answered for the respondent to be included in the analysis.

Ethics

The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics pre-approved each data collection separately (ref. 4.2006.794 and ref. 2018/2149). All responses were anonymous. Completing the questionnaire implied consent to participate and for anonymous information to be stored.

Results

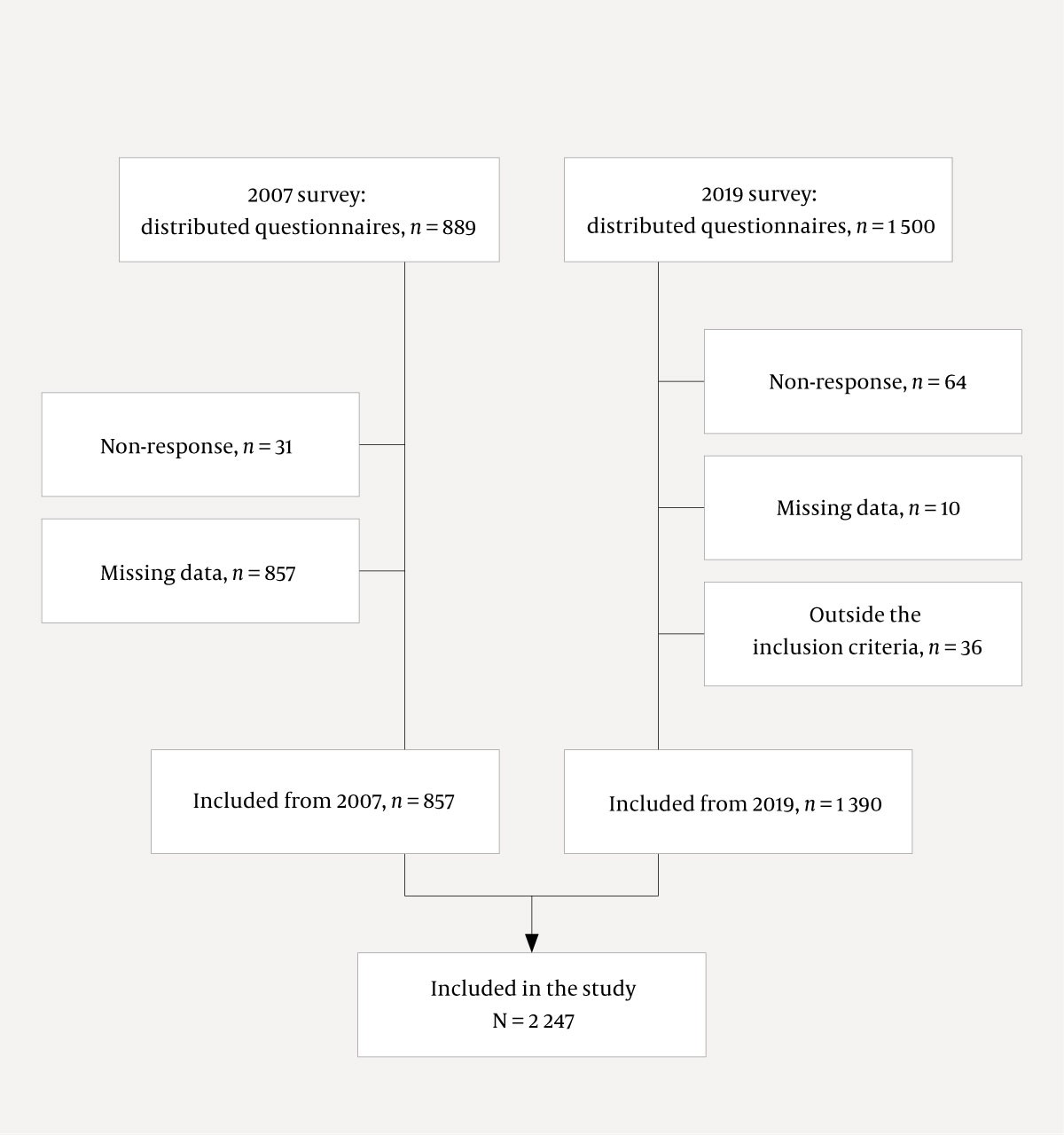

In 2007, 858/889 (96.5 %) distributed questionnaires were answered and returned, and 1,436/1,500 (95.7 %) were returned in 2019. Of a total of 2,294 respondents, 2,247 met the inclusion criteria and were included in further analyses (Figure 1). Respondents from all Norwegian counties and all faculties at NTNU were represented in the 2019 data, but geographical origin and faculty affiliation were not captured in 2007. Descriptive characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The proportion of female participants was higher in 2019 than in 2007.

Table 1

Descriptive characteristics of the study population: students recruited during breaks in well-attended lectures at NTNU in 2007 and 2019. Mean and standard deviation unless otherwise specified.

| Variables | 2007 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women, n (%) | 363 (42.3) | 758 (54.9) | |

| Age | 21.5 (2.4) | 22.5 (2.7) | |

| No. of years studied | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.7) | |

| Age started drinking alcohol | 15.2 (2.2) | 16.3 (1.8) | |

| No. of units of alcohol in last drinking episode1 | 7.4 (4.5) | 6.0 (4.1) | |

| AUDIT score | |||

| Women | 9.9 (4.3) | 8.2 (4.8) | |

| Men | 11.2 (5.0) | 8.9 (5.2) | |

| Total | 10.7 (4.7) | 8.5 (5.0) | |

1Students who do not drink alcohol were excluded, n=41 in 2007 and n=90 in 2019

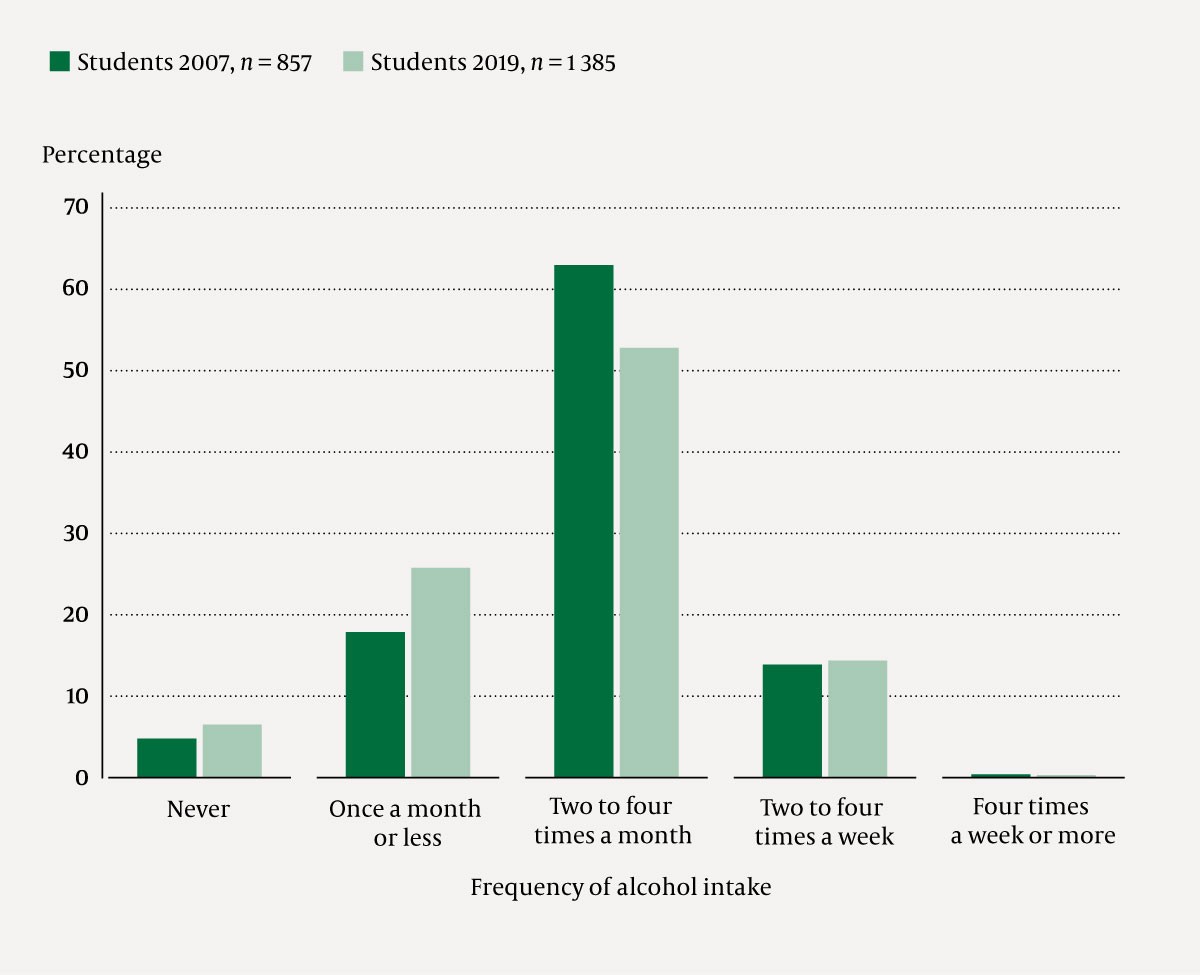

In the surveys, 41/857 (4.8 %) students from 2007 and 90/1,385 (6.5 %) students from 2019 reported being completely abstinent (chi-square test, p < 0.001). In 2019, 937/1,385 (67.6 %) students drank alcohol 'two to four times a month' or more frequently. This represented a reduction from 2007 of 9.8 % (chi-square test, p < 0.001). Correspondingly, the proportion who drank 'once a month or less' increased by 7.9 % (Figure 2). This shift was statistically significant (Mantel-Haenszel test for trend, p < 0.001).

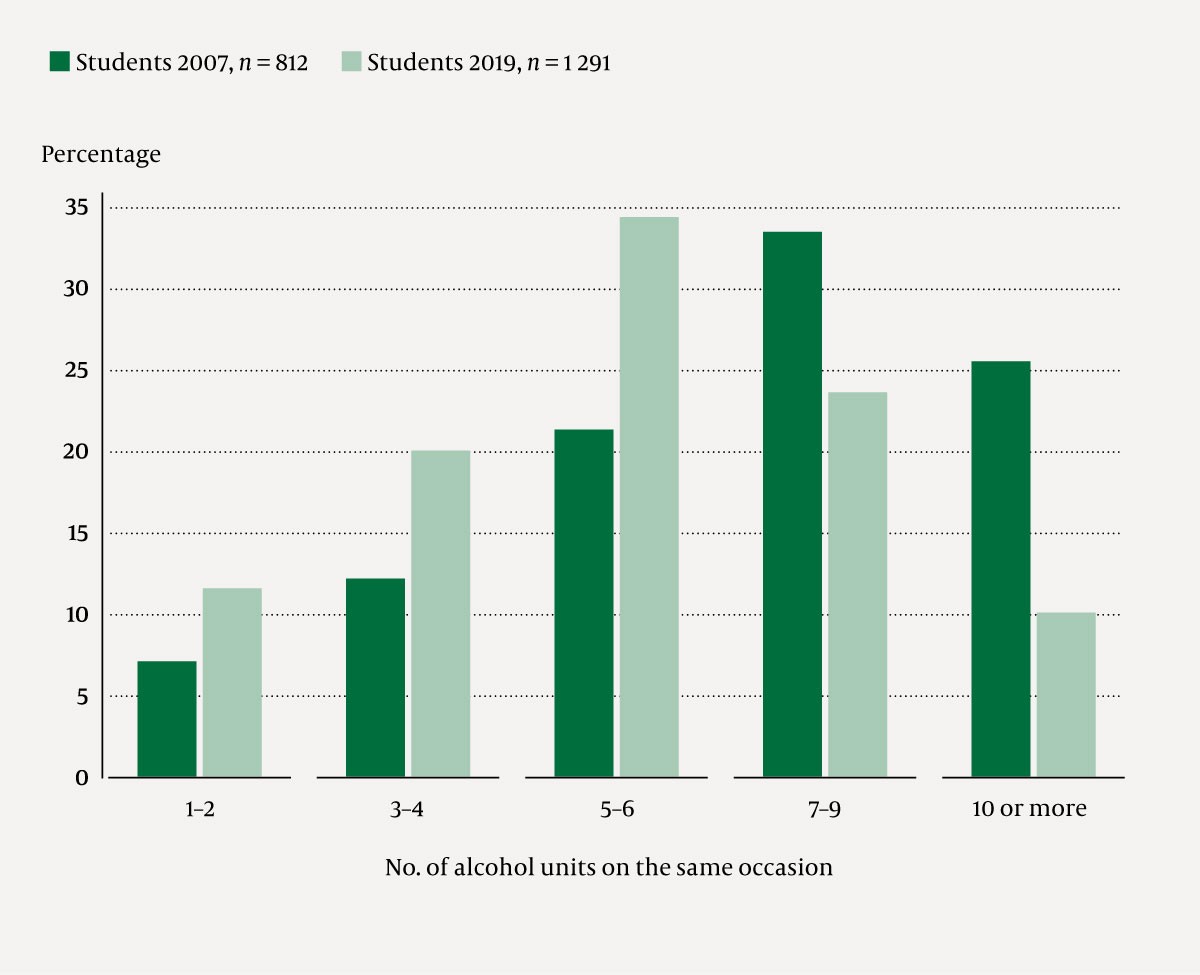

In the surveys, 655/814 (80.5 %) students in 2007 and 885/1,386 (67.8 %) students in 2019 drank five units of alcohol or more on a typical drinking day (classified as binge drinking (10)). Over the time period in question, there has been an absolute reduction of 12.8 % in this category (chi-square test, p < 0.001). Figure 3 illustrates the significant leftward shift in students' alcohol consumption from 2007 to 2019 (Mantel-Haenszel test for trend, p < 0.001). The largest reduction occurred in the category '10 or more units', with a 15.5 % lower prevalence among students in 2019, followed by a 10.1 % reduction in the category '7–9 units' compared to 2007. There was a corresponding increase in the lower categories 1–6 units. The leftward shift in alcohol consumption was observed for both sexes (Table 2, Mantel-Haenszel test for trend, p < 0.001).

Table 2

Amount of alcohol consumed on the same occasion among NTNU students in 2007 and 2019, by sex. Students who do not drink alcohol were excluded from the analyses. Figures are presented as absolute numbers (%). The sex-based differences in number of alcohol units were statistically significant in both 2007 and 2019 (chi-square test, p < 0.001). The development in alcohol intake in both the male and female categories in the period 2007–19 was statistically significant (Mantel-Haenszel test for trend, p < 0.001).

| 2007 | 2019 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol units on same occasion | Women (n = 351) | Men (n = 461) | Total (n = 812) | Women (n = 719) | Men (n = 562) | Total (n = 1,281) | |

| 1–2 units | 22 (6.3) | 36 (7.8) | 58 (7.1) | 99 (13.8) | 51 (9.1) | 150 (11.7) | |

| 3–4 units | 62 (17.7) | 37 (8.0) | 99 (12.2) | 164 (22.8) | 91 (16.2) | 255 (19.9) | |

| 5–6 units | 111 (31.6) | 63 (13.7) | 174 (21.4) | 288 (40.1) | 154 (27.4) | 442 (34.5) | |

| 7–9 units | 120 (34.2) | 153 (33.2) | 273 (33.6) | 142 (19.7) | 163 (29.0) | 305 (23.8) | |

| 10 units or more | 36 (10.3) | 172 (37.3) | 208 (25.6) | 26 (3.6) | 103 (18.3) | 129 (10.1) | |

In 2019, an average of 6.0 alcohol units (SD = 4.2) were consumed in the last drinking episode among students who drank alcohol. This represented an absolute reduction of 1.4 alcohol units from 2007 (independent t-test, p < 0.001). In 2019, men drank an average of 7.2 units of alcohol (SD = 4.9) in the last drinking episode, compared to 8.5 units (SD = 5.0) in 2007. For women, the corresponding figures were 5.1 units (SD = 3.2) in 2019 and 6.0 units (SD = 3.2) in 2007. The sex-based differences were statistically significant (independent t-test, p < 0.001).

Students' mean AUDIT score was 10.7 (SD = 4.7) in 2007 and 8.5 (SD = 5.0) in 2019 (independent t-test, p < 0.001). In 2019, 766/1,370 (55.9 %) students had an AUDIT score ≥ 8, which represents a shift from low-risk to risky/potentially harmful consumption. In 2007, the corresponding figure was 599/802 (74.7 %) students. The proportion of students with risky alcohol use was significantly reduced by 18.8 % from 2007 to 2019 (chi-square test, p < 0.001), while an increase was observed in the low-risk group. Reductions were observed in both high-risk groups (Figure 4, chi-square test, p < 0.001). In 2007, 37/802 students (4.6 %) had an AUDIT score corresponding to very high risk/probable alcohol dependence (chi-square test, p < 0.001), compared to 41/1,370 (3.0 %) students in 2019.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine alcohol use trends among NTNU students in a twelve-year perspective. We identified moderate reductions in the frequency of alcohol intake, the quantity of alcohol consumed, and the occurrence of binge drinking among students in the period 2007–19. The proportion of students with risky alcohol use as determined by the AUDIT scores fell by as much as 19 % between 2007 and 2019, but the alcohol use of over half of the students still poses a long-term risk.

Consuming five or more units of alcohol on the same occasion is classified as binge drinking (10). Frequent binge drinking increases the risk of negative alcohol-related consequences, including injuries, physical violence and sexual assault (15). The reduction in binge drinking trends found in this study is therefore positive from a public health perspective. Our findings related to binge drinking show that this is more common at NTNU (68 %) than among students in Bergen (61 %) (8) and students nationwide (student health and satisfaction survey, the SHoT study; 57 %) (13, 14). The difference must be viewed in the context of the higher average age of students in the Bergen study (24.9 years), as well as the lower proportion of male participants in both studies (8, 13). Previous studies have shown that the tendency to binge drink decreases with increasing age, and that men drink larger quantities and more frequently than women (5, 8, 11, 13).

The high proportion of students with risky alcohol use in our study is consistent with results from previous studies showing a high prevalence of risky alcohol use among students in Norway (8, 12, 13). Erevik et al. found that the prevalence of risky alcohol use among students in Bergen in 2015 was 53 % (8), while the SHoT survey in 2018 reported risky alcohol use in 43 % of students nationwide (13). In our data, the proportion was somewhat higher, at 56 % in 2019. Caution should be exercised when interpreting the difference in results between NTNU and Bergen students due to the variations in average age and sex distribution. The prevalence of risky alcohol use among students is considerably higher than in the general population, where 15 % have risky alcohol use according to a survey by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. In the segment of the general population most comparable to the student population (16–24 years), the proportion was 34 % (5).

Based on the data from the SHoT study, Heradstveit et al. examined the extent and development of risky alcohol use among Norwegian students in the period 2010–18. Their results showed that the prevalence of risky/potentially harmful alcohol use has been stable over the past eight years (12). This is in contrast to our study, where the proportion of NTNU students with risky alcohol use fell significantly, by 19 % in the period 2007–19 (Figure 3).

Data from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT3) have shown that alcohol intake varies throughout the year, with the highest consumption in the summer and early autumn (17). It is reasonable to assume that there may also be a similar seasonal variation among students, as the autumn semester includes an introduction programme for new students (buddy week) and (in odd-numbered years) Norway's largest cultural festival 'UKA'. The survey in 2007 was conducted in the spring, while in 2019 the data were collected in the autumn. Assuming a seasonal variation with increased alcohol consumption in the autumn semester, the reduction in alcohol consumption among NTNU students may be greater than observed in this study. The timing of the data collection for the SHoT surveys also differed: autumn 2010 and spring 2018. This reverse seasonal variation may also have resulted in a smaller relative difference between the samples (12).

In the SHoT survey from 2010, two-thirds of the students reported problematic high alcohol consumption levels in student environments and called for more alcohol-free options. This proportion was lower in the SHoT survey from 2018 (13), which may suggest that this data also reflects a change in students' drinking habits and attitudes that is consistent with the trends observed in our study. Our results indicate that the prevalence of risky alcohol use among NTNU students, just like minors and the general adult population, has fallen over the last decade (5, 18). The reasons for this shift are unclear, as national measures such as taxation and reduced availability have remained the same. Changing attitudes in the student community and the correspondingly stronger focus on alcohol-free options may have contributed to the reduction.

The data from the SHoT survey in 2018 represent the most comprehensive survey of Norway's student population, with over 50,000 participating students, but the response rate was low (31 %) (13). Our study includes only 3.9 % of NTNU's student population in 2019 but has a high response rate (96 %). The difference in response rate is probably a result of methodological differences; the SHoT survey is conducted online, while the NTNU survey was via a printed questionnaire, which generally leads to higher participation (19).

The SHoT survey has the capability to capture the entire student population since it is conducted online, but its low response rate makes it vulnerable to sample bias. For example, selection bias can result in an overrepresentation of students with low to moderate alcohol consumption, as these may be more likely to respond. This represents a subgroup in our dataset that has changed little between the survey periods. Our own study only captures students who attend lectures. Our measures to ensure a representative sample among these students included attendance at various faculties and at different times of the day. Our study has a high response rate and demographic diversity. It is therefore reasonable to assume that a representative sample across the student population has been achieved.

The use of only two measurement points is a major methodological limitation in the study that restricts the opportunities for commenting on ongoing trends during the time period in question. Relevant findings therefore need to be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Our results suggest a moderate reduction in alcohol consumption among NTNU students and a significant decrease in the proportion engaging in risky alcohol use from 2007 to 2019. However, the prevalence of risky/potentially harmful alcohol use among students is still high compared to that of the general population. Based on this, there is a clear need to investigate the long-term consequences of students' alcohol consumption and whether drinking habits formed as students have implications for future health.

- 1.

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639 Accessed 17.10.2023.

- 2.

Murray CJ, Aravkin AY, Zheng P et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396: 1223–49. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Barbor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J et al. AUDIT - The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MSD-MSB-01.6a Accessed 17.10.2023.

- 4.

ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. QE10 Hazardous alcohol use. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/499098434 Accessed 26.8.2023.

- 5.

Bye EK, Rossow IM. Alkoholbruk i den voksne befolkningen. https://www.fhi.no/le/alkohol/alkoholinorge/omsetning-og-bruk/alkoholbruk-i-den-voksne-befolkningen/?term= Accessed 17.10.2023.

- 6.

Wicki M, Kuntsche E, Gmel G. Drinking at European universities? A review of students' alcohol use. Addict Behav 2010; 35: 913–24. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Bingham CR, Shope JT, Tang X. Drinking behavior from high school to young adulthood: differences by college education. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005; 29: 2170–80. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Erevik EK, Pallesen S, Vedaa Ø et al. Alcohol use among Norwegian students: Demographics, personality and psychological health correlates of drinking patterns. Nordisk Alkohol Nark 2017; 34: 415–29. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Davis CN, Slutske WS, Martin NG et al. Genetic Epidemiology of Liability for Alcohol-Induced Blacking and Passing Out. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2019; 43: 1103–12. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/key-substance-use-and-mental-health-indicators-united-states-results-2016-national-survey Accessed 17.10.2023.

- 11.

White AM, Kraus CL, Swartzwelder H. Many college freshmen drink at levels far beyond the binge threshold. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006; 30: 1006–10. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Heradstveit O, Skogen JC, Brunborg GS et al. Alcohol-related problems among college and university students in Norway: extent of the problem. Scand J Public Health 2021; 49: 402–10. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Knapstad M, Heradstveit O, Sivertsen B. SHoT 2018. Studentenes helse- og trivselsundersøkelse. https://khrono.no/files/2018/09/05/SHOT%202018%20(1).pdf Accessed 17.10.2023.

- 14.

Sivertsen B, Johansen MS. Studentenes helse- og trivselsundersøkelse. Hovedrapport 2022. https://studenthelse.no/SHoT_2022_Rapport.pdf Accessed 17.10.2023.

- 15.

White A, Hingson R. The burden of alcohol use: excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res 2013; 35: 201–18. [PubMed]

- 16.

Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test. Addiction 1995; 90: 1349–56. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 17.

Knudsen AK, Skogen JC. Monthly variations in self-report of time-specified and typical alcohol use: the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT3). BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 172. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 18.

Pape H, Rossow I, Brunborg GS. Adolescents drink less: How, who and why? A review of the recent research literature. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018; 37 (Suppl 1): S98–114. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 19.

Dykema J, Stevenson J, Klein L et al. Effects of E-Mailed Versus Mailed Invitations and Incentives on Response Rates, Data Quality, and Costs in a Web Survey of University Faculty. Soc Sci Comput Rev 2013; 31: 359–70. [CrossRef]