A pregnant woman in her thirties with abdominal pain, seizures and haemorrhagic shock

A pregnant woman at term was admitted to the emergency department with abdominal pain, generalised seizures and haemorrhagic shock. An outpatient check-up five days earlier showed good general condition, normal blood pressure and normal fetal heartbeat.

A woman in her thirties contacted the midwife on duty because of nausea, vomiting and pain under the right costal arch. She was primiparous and in gestational week 37 + 6, and had felt fetal movement earlier in the day. It was agreed that she should come in for an examination. Six minutes later, the Emergency Medical Communication Centre informed the midwife that the patient's husband had called to say that the patient was having seizures.

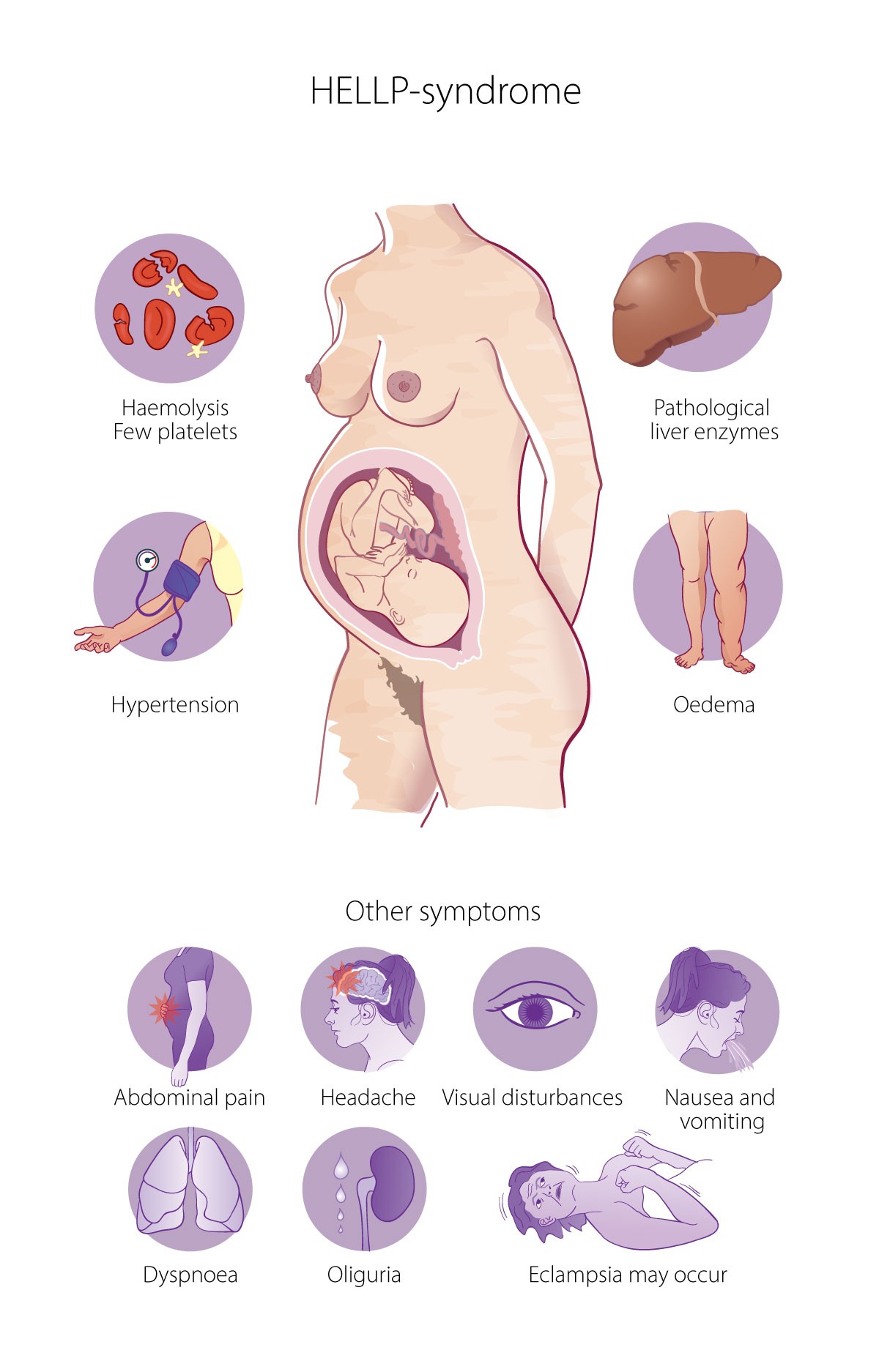

The symptoms could give rise to suspicion of preeclampsia, and seizures in a pregnant woman are eclampsia until proven otherwise. Preeclampsia is defined as new-onset hypertension (blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg systolic or ≥ 90 mmHg diastolic) after gestational week 20, and at least one other new-onset sign of maternal or fetal organ involvement. Symptoms and signs include proteinuria, elevated liver transaminase levels, epigastric pain, headache, visual disturbances, haematological abnormalities and fetal growth restriction. Eclampsia refers to generalised seizures that occur during pregnancy, labour or the first seven days after delivery, with concomitant preeclampsia or gestational hypertension without other neurological aetiology (1, 2).

The patient was found to have eclampsia, but preeclampsia had not been suspected at a check-up five days earlier in gestational week 37 + 1. At that point, her blood pressure was normal (128/79 mmHg). The fetus was somewhat smaller than average (−13 %), and a new fetal growth assessment was arranged for 14 days later. No urine sample was taken. After the check-up, the patient displayed mild symptoms; lower back pain, tight abdomen and discomfort on deep inspiration. The day before admission, the patient had contacted the maternity ward because of nausea and vomiting. She could feel fetal movements, and the midwife found no indication for another check-up. The patient had a normal haemoglobin level in the first trimester of 13.5 g/dL (reference range 11.7–15.3) and a normal routine scan at gestational week 17 + 6.

After 20 minutes, on the way to hospital, the Emergency Medical Communication Centre reported that the patient was pale and clammy and had a pulse of 140 beats/min. Oxygen saturation and blood pressure were difficult to measure and her radial pulse was not palpable. The first systolic blood pressure recorded in the ambulance was 88 mmHg, falling to 44 mmHg just before arrival at the hospital. The ambulance record notes that the patient was wakeful. No urine leakage or external injuries were observed.

Approximately 45 minutes after the first phone call, the patient arrived at the emergency department and was received by the emergency medical team consisting of gynaecologists, midwives, anaesthesia personnel and internal medicine clinicians. She had woken up and was responding in short sentences. Her GCS (Glasgow Coma Scale) score was 14. She was cold, clammy and had grey skin and rapid respiration. Her oxygen saturation was 99 % without supplemental oxygen, and her pulse was 160 beats/min. Blood pressure measured using an arterial cannula was 60/40 mmHg. No vaginal bleeding was observed. Abdominal ultrasound in a stable recovery position revealed no detectable fetal heartbeat. Six minutes after arrival, the woman was wheeled to the operating theatre on the ambulance stretcher. The gynaecologist informed the paediatrician on duty.

Impaired consciousness, high pulse, low blood pressure and clammy skin are clinical signs of haemorrhagic shock. We chose not to perform a standard abdominal ultrasound according to the trauma protocol (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST)) because the patient was haemodynamically unstable, and we suspected haemorrhaging of obstetric aetiology. In a pregnant woman, haemorrhagic shock is most often caused by placental abruption (abruptio placentae), placenta covering the opening of the cervix (placenta previa), or fetal membranes with large blood vessels (vasa previa) (3, 4). Vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms.

The patient was anaesthetised with ketamine and suxamethonium and intubated without complication. She was covered in a sterile surgical drape with no abdominal skin antiseptic. Blood transfusion was started. A low transverse incision was made to the skin, and the peritoneum opened. Large amounts of blood drained out. Uterotomy was performed. The amniotic fluid was normal.

Fifteen minutes after arriving at the emergency department, a lifeless infant was born, the umbilical cord was clamped and cut, and the infant was taken to the waiting paediatricians. The placenta was macroscopically normal, but subsequent histological examination revealed a birth weight in the 25th percentile for gestational age and sparse pathological changes. The uterotomy was closed in two layers. The focus of bleeding in the lesser pelvis was not found, and the abdomen was packed. The patient was hypotensive (approximately 90/40 mmHg) and tachycardic (approximately 110 beats/min.). When the upper abdominal compresses were removed, the abdomen refilled with blood. The abdomen was repacked, a midline incision was made for better access, and bleeding was found from Morison's pouch between the liver and right kidney.

The general surgeon on call was called, the incision was widened further, and two superficial liver lacerations of 2.5 × 1 cm and 10 × 1.5 cm in segments 5 and 6/7 respectively were revealed. The areas bled but no defined blood vessels were found that could be suture ligated. Control of primary bleeding was achieved through compression of the liver and targeted packing with compresses. Haemostasis was achieved with collagen sponges (TachoSil) and abdominal vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) was performed for temporary closure of the abdomen.

Results of blood tests taken upon arrival at the hospital arrived perioperatively and showed haemoglobin 11.6 g/dL, platelets 20 × 109/L (150–450 × 109), haptoglobin 0.1 g/L (0.4–1.9), bilirubin 62 µmol/L (5–25), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 509 U/L (15–35), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 714 U/L (< 45) and D-dimer 20 mg/L FEU (< 0.5). This confirmed the suspicion of HELLP syndrome.

HELLP syndrome involves haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count. The condition is associated with preeclampsia and is detected by a low serum haptoglobin level (< 0.1 g/L) or elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase and/or bilirubin, and elevated levels of liver transaminases as well as a low platelet count (< 100 × 109/L) (Figure 1). The syndrome is unpredictable and can progress rapidly (1, 2).

Once the liver bleeding was under control, the patient's condition stabilised. She was transferred intubated to the intensive care unit. Postoperative haemoglobin level was around 11 g/dL, ECG showed sinus rhythm, pulse was 90 beats/min. and mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg. Total bleeding was estimated at 3.3 L. Perioperatively, the patient was transfused with 6 erythrocyte (SAG), 4 plasma and 2 platelet concentrates, and additionally received the following intravenously: tranexamic acid 1 g, calcium 5 mmol, oxytocin (Syntocinon) 10 IU, metronidazole 1.5 g and cefuroxime 1.5 g.

After a day and a half, the patient was taken in for a planned second look. There was less blood in the abdomen, but pronounced oedema of the liver. The collagen sponges were intact, but due to the oedema, the lacerations had increased in size to 11 × 3.5 cm and 2 × 4 cm. Venous bleeding was seen where the lacerations were not covered with haemostatic products. Bleeding was brought under control with new collagen sponges and new abdominal VAC was performed.

At the third look two days later, there was no bleeding and the hepatic oedema had decreased. The abdomen was closed and abdominal drain inserted. Low molecular weight heparin 5,000 IU × 1 was started subcutaneously for thromboprophylaxis. After six days in the intensive care unit, the patient was transferred to the maternity ward in good condition, with improvements in blood tests: haemoglobin 10.9 g/dL, platelets 194 × 109/L, haptoglobin 1.4 g/L, bilirubin 17 µmol/L, AST 60 U /L and ALT 190 U/L.

Kidney failure, pulmonary oedema, coagulation disorders, placental abruption, eclampsia and brain injury, as well as necrosis, rupture and bleeding of the liver are among the most serious complications of HELLP syndrome (2, 5). Ruptured subcapsular liver haematoma occurs in 1–2 % of patients (6). Spontaneous liver rupture is extremely uncommon. Symptoms can include epigastric pain, pain in the right shoulder, nausea, vomiting and dyspnoea. The incidence of ruptured subcapsular liver haematoma varies from 1 per 40 000 to 1 per 250 000 pregnancies (6). In this case, we suspected traumatic liver laceration caused by the seizures. Several methods can be used to treat haemorrhagic hepatic lesions. We used collagen sponges, which we placed directly on the liver. These contain human fibrinogen and human thrombin and work by sealing the tissue.

The haptoglobin level normalised in the first week, but suddenly dropped to < 0.1 g/L nine days after admission. Platelets were 216 × 109/L and D-dimer > 20.0 mg/L FEU. Other coagulation tests were normal. The patient had no subjective symptoms at this time, but the haematologists were puzzled by the sudden drop in haptoglobin level and requested a CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis. The scan revealed a large saddle pulmonary embolism. The dose of low molecular weight heparin was increased to 10 000 IU × 2 subcutaneously. The patient was symptom-free and mobilised in the ward. She was discharged after a total of three weeks in hospital.

Five days later, the woman made contact again because of pain in the abdomen and thorax. Reduced respiratory sounds were found over the right lung. Her pulse was 130 beats/min. and blood pressure 122/85 mmHg. A chest X-ray showed large right-sided pleural effusion. She was admitted to the pulmonary department, and had approximately 2000 mL of dark-coloured blood drained. She was discharged again after three days.

Severe illness and immobilisation increase the risk of venous emboli. It is estimated that more than half of intensive care patients are at risk of developing venous thromboembolism (7). The pulmonary embolism and pleural haemorrhage in our patient were probably triggered by a combination of coagulation disorders due to HELLP syndrome and a thrombogenic condition as a result of emergency surgery and serious illness.

Thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin is recommended after caesarean section and for critically ill patients (2). However, in the case of ongoing bleeding or a high risk of bleeding, it is recommended to wait until the risk subsides before starting treatment with low molecular weight heparin.

In this patient, the risk of bleeding was assessed as high, with low platelet levels and liver lacerations. Due to the risk of bleeding, we chose to delay thrombosprophylaxis until after the third operation, when it was certain that there were no longer any haemorrhagic hepatic lesions. The patient was given mechanical thromboprophylaxis and high compression stockings. Her subsequent development of both pulmonary embolism and haemothorax illustrates the difficulty of balancing the risk of thrombosis and bleeding in a critically ill patient with HELLP syndrome.

At follow-up with a haematologist six weeks postoperatively, the patient was symptom-free. She was put on apixaban 5 mg × 2 orally for six months, and it was recommended that she receive thromboprophylaxis in risk situations such as pregnancy. At the six-month follow-up, she was still symptom-free. All thrombophilia tests were normal.

The infant

The baby boy, with a birth weight of 2900 grams, was taken to the resuscitation room outside the operating theatre. As the mother's condition had deteriorated so rapidly, the paediatricians decided to attempt resuscitation of the infant, despite being aware that there had been no heartbeat for at least ten minutes. He was intubated immediately. Cardiac compressions were started after around one minute of ventilation with no detectable heartbeat.

The infant's skin colour improved from white to bluish pink. The pulse oximeter showed a synchronous compression curve with SpO2 of 80–95 % from an age of around five minutes. After seven minutes, the infant had a detectable heartbeat of around 50 beats/min. This repeatedly rose to around 140 beats/min. but fell again such that cardiac compressions had to be resumed after brief pauses. The infant had a sustained spontaneous heartbeat over 100 beats/min. from around the age of 30 minutes. Five doses of 0.5 mL emergency adrenaline 0.1 mg/mL, 73 mL isotonic saline, 45 mL emergency blood and 10 mL glucose 100 mg/mL were administered in the umbilical vein during resuscitation.

Apgar score was 0 - 1–2, with one point for colour at five minutes, and one for colour and one for heartbeat at ten minutes. Arterial cord blood samples showed pH 6.63, pCO2 18.8 kPa, pO2 2.24 kPa, base excess (BE) −22.8 mmol/L, glucose 0.82 mmol/L, and haemoglobin 15.6 g/dL. Lactate level was not measurable. At 90 minutes old, pH was 6.72, pCO2 6.88 kPa, pO2 10.8 kPa, BE −29.7 mmol/L, haemoglobin 19.2 g/dL, glucose 9.5 mmol/L and lactate 16 mmol/L.

The infant was transferred to the university hospital for hypothermia treatment due to severe perinatal asphyxia, but unfortunately showed no signs of alertness. His pupils were fixed and dilated, EEG was flat, and he developed multiorgan failure. After a day and a half of hypothermic treatment, it was decided not to go ahead with further treatment. At this time, the mother was still intubated in the intensive care unit between the first and second surgery, and the father did not want to leave her. The anaesthetists considered her to be sufficiently stable for it to be safe to waken her. We chose to bring the infant back to the local hospital before stopping respiratory therapy and vasoactive support so that the parents could see their son and say their goodbyes to him.

Discussion

In this case report, we describe a patient who developed serious complications of HELLP syndrome. The symptoms were sudden, and her condition deteriorated rapidly. The mother's life was saved, but the infant died.

In the period 1996–2014, 16 women in Norway died of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (8), compared to one in the period 2012–2018. Internationally, the figures are higher (9, 10), and maternal mortality from HELLP syndrome can be up to 25 % (1). One of the main reasons for the low mortality in Norway is the good and quick access to health care (11). This highlights the need to remain extremely vigilant for symptoms and signs and to provide prompt treatment if HELLP syndrome is suspected. Quick notification and good communication throughout the emergency medical chain were essential for the patient surviving this dramatic event. A caesarean section was performed promptly after she arrived at the hospital. Despite good teamwork and rapid action, the infant died and the mother suffered serious complications.

Our patient was previously healthy. She had been in contact with the specialist health service for the first time five days before the event, with no symptoms of preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome being detected. Unfortunately, no urine sample was taken. Detection of proteinuria could have prompted blood tests and checks at an earlier stage. If signs of incipient HELLP syndrome had been detected, it is likely that the woman would have been asked to come to the hospital for examination when she reported nausea and vomiting the day before admission, and the acute event might have been avoided. Sparse histological changes in the placenta, however, fit best with the rapid onset of symptoms. Nevertheless, the case study serves as a reminder to check for proteinuria, as recommended for prenatal check-ups.

The risk for HELLP syndrome is 10–40 % higher in a new pregnancy (1, 2, 12). Our patient has been advised to wait at least a year due to the serious complications. If she falls pregnant again, she must be closely monitored in an outpatient clinic and receive prophylactic treatment with low molecular weight heparin and acetylsalicylic acid during pregnancy and low molecular weight heparin for at least six weeks after giving birth.

In Norway, very few children die as a result of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Internationally, the estimated fetal mortality in HELLP syndrome is 6–37 % (1, 13). Most deaths are due to premature placental abruption, fetal asphyxia or prematurity. In our case, the infant died of asphyxia due to maternal haemorrhagic shock. Neonates have a remarkable tolerance to hypoxia (14). Degree of metabolic acidosis in umbilical arterial blood gives an indication of prognosis. With a base excess (BE) of less than −16 mmol/L, 40 % of neonates will develop moderate to severe complications (15).

The umbilical arterial BE level in the infant in this case study was −22.8 mmol/L with an Apgar score of 0 - 1–2, which indicates a high probability of severe brain damage. Whether it was right to continue resuscitation for as long as we did can be debated. Signs of response in the form of a pink colour, good oxygen saturation and heartbeat contributed to our decision to continue. With the benefit of hindsight, it would perhaps have been reasonable to stop when, at the age of 20 minutes, the infant had not shown a persistent spontaneous heartbeat over 100 beats/min.

The decision to bring the intubated child back to the local hospital after it was decided to end treatment, and to wake the mother to say goodbye to her son despite her packed abdomen, was thoroughly discussed amongst the clinicians. Continuing pointless intensive therapy in the infant was considered unethical. Meanwhile, the mother's blood pressure was potentially unstable, with a risk of further heamorrhageing. The literature suggests that being with the infant when he/she dies can help ease the grieving process for the parents (16). Difficult decisions must be resolved as a team and may require non-traditional solutions. The patient and her husband are grateful for the opportunity to see their son and say their goodbyes to him.

The patient (the infant's mother) and the infant's father consented to publication of the article.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Haram K, Bjørge L, Guttu K. HELLP-syndromet. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2000; 120: 1433–6. [PubMed]

- 2.

Staff A, Kvie A, Langesæter E et al. Hypertensive svangerskapskomplikasjoner og eklampsi. https://www.legeforeningen.no/foreningsledd/fagmed/norsk-gynekologisk-forening/veiledere/veileder-i-fodselshjelp/hypertensive-svangerskapskomplikasjoner-og-eklampsi/ Accessed 16.12.2021.

- 3.

Oyelese Y, Smulian JC. Placenta previa, placenta accreta, and vasa previa. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107: 927–41. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Staff A, Holme AM, Turowski G et al. 2021. Placenta. https://www.legeforeningen.no/foreningsledd/fagmed/norsk-gynekologisk-forening/veiledere/veileder-i-fodselshjelp/placenta/ Accessed 16.12.2021.

- 5.

Kaltofen T, Grabmeier J, Weissenbacher T et al. Liver rupture in a 28-year-old primigravida with superimposed pre-eclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and low platelet count syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2019; 45: 1066–70. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

Kanonge TI, Chamunyonga F, Zakazaka N et al. Hepatic rupture from haematomas in patients with pre-eclampsia/eclampsia: a case series. Pan Afr Med J 2018; 31: 86. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Anderson FA, Zayaruzny M, Heit JA et al. Estimated annual numbers of US acute-care hospital patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Am J Hematol 2007; 82: 777–82. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Nyfløt LT, Ellingsen L, Yli BM et al. Maternal deaths from hypertensive disorders: lessons learnt. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018; 97: 976–87. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Nyfløt LT, Ellingsen L, Vangen S. Hvorfor dør kvinner av graviditet i Norge i dag? https://oslo-universitetssykehus.no/seksjon/nasjonal-kompetansetjeneste-for-kvinnehelse/Documents/M%C3%B8dred%C3%B8dsrapport%202021_web.pdf Accessed 13.2.2023.

- 10.

Jentoft S, Nielsen VO, Roll-Hansen D. Hvor mange kvinner dør i svangerskapet? Samfunnspeilet 2.5.2011. https://www.ssb.no/helse/artikler-og-publikasjoner/hvor-mange-kvinner-dor-i-svangerskap Accessed 13.2.2023.

- 11.

Engjom HM, Morken NH, Høydahl E et al. Risk of eclampsia or HELLP-syndrome by institution availability and place of delivery - A population-based cohort study. Pregnancy Hypertens 2018; 14: 1–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Skjaerven R, Wilcox AJ, Lie RT. The interval between pregnancies and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 33–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Haavaldsen C, Strøm-Roum EM, Eskild A. Temporal changes in fetal death risk in pregnancies with preeclampsia: Does offspring birthweight matter? A population study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X 2019; 2: 100009. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Rainaldi MA, Perlman JM. Pathophysiology of Birth Asphyxia. Clin Perinatol 2016; 43: 409–22. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 348, November 2006: Umbilical cord blood gas and acidbase analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108: 1319–22. [PubMed]

- 16.

Brosig CL, Pierucci RL, Kupst MJ et al. Infant end-of-life care: the parents' perspective. J Perinatol 2007; 27: 510–6. [PubMed][CrossRef]

I serien Noe å lære av har Kristoffersen og medarbeidere en bred og vel illustrert kasuistikk om HELLP syndrom (1).

Betegnelsen HELLP henspeiler på de sentrale patofysiologiske elementene (Hemolysis), patologiske leverfunksjonsprøver (Elevated Liver enzymes) og trombocytopeni (Low Platelets). Tilstanden er sjelden, men er rapportert ved opptil 10% av alle tilfeller med preeklampsi (2), det vil si omtrent 150 tilfeller per år i Norge og klart hyppigere enn eklampsi.

Som det fremgår av kasuistikken kan sykdommen progrediere svært raskt og være livstruende. Årvåkenhet og bred kjennskap til tilstanden blant helsepersonell er essensielt for tidlig påvisning, men diagnosen er ofte vanskelig fordi symptomer som kvalme, brekninger og smerte under høyre kostalbue eller i epigastriet lett kan mistolkes og forsinke diagnosen. Kasuistikken illustrerer dette.

Etter siste svangerskapskontroll og fem dager før innleggelsen hadde pasienten fått milde symptomer med korsryggsmerter, stram mage og ubehag ved dyp inspirasjon. Dagen før innleggelsen kontaktet hun fødeavdelingen på grunn av kvalme og oppkast. Jordmor fant ikke indikasjon for ny kontroll. Dagen etter varslet mannen AMK om kramper. Det ble raskt utført hastekeisersnitt. Det forelå massiv intraabdominal blødning på grunn av blødende leverlaserasjoner. Mor overlevde, men barnet lot seg ikke resuscitere.

Vi mener kasuistikken illustrer hvor viktig det er med både klinisk undersøkelse og blodprøvetaking samme dag som en gravid, i siste halvdel av graviditeten, rapporterer symptomer som kvalme og oppkast.

I diskusjonen nevnes nytten av proteinuri som tidlig markør for mulig HELLP-utvikling, men selv om urinundersøkelse hører med ved alle kontroller bør det også presiseres at de klassiske preeklampsi symptomer, hypertoni og proteinuri, i en del tilfeller ikke er til stede i sykdommens tidlige fase (3).

I 1982 lanserte Weinstein HELLP-syndromet (3). Allerede 1984 publiserte Øian og medarbeidere den første publikasjonen i Norden (4). I Norge ble syndromet relativt raskt kjent, og kunnskapen implementert klinisk, i undervisningen og i Legeforeningens veiledere i fødselshjelp fra 1995 (5,6).

Litteratur:

1. Kristoffersen I, Holte K, Antonsen LP et al. En gravid kvinne i 30-årene med magesmerter, kramper og blødningssjokk. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2023 Mar27;143(5).; doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.22.0282. Print 2023 Mar 28.

2. Olié V, Moutengou E, Grave C et al. Prevalence of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy in France (2010-2018): The nationwide CONCEPTION study. J Clin Hypertens 2021; 23(7): 1344-1353.

3. Weinstein L. Syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count: a severe consequence of hypertension in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982; 142(2): 159-67.

4. Øian P, Maltau JM, Åbyholm T. HELLP syndrome – a serious complication of hypertension in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984; 63(8): 727-9.

5. Bergsjø P, Maltau JM, Molne K et al. Obstetrikk og gynekologi. I: Maltau JM, Øian P, red. Sene svangerskapskomplikasjoner. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk, 1993.Bergsjø P, Maltau JM, Molne K, Nesheim BI (eds). Obstetrikk og gynekologi. Kapittel 12: Maltau JM, Øian P: Sene svangerskapskomplikasjoner. Gyldendal Akademisk 1993.

6. Øian P, Henriksen T, Sviggum O. Kapittel 26: Hypertensive svangerskapskomplikasjoner. Veileder i fødselshjelp 1995. Norsk gynekologisk forening. https://www.nb.no/maken/item/URN:NBN:no-nb_digibok_2008022704071/open Lest 26.5.2023Veileder i fødselshjelp 1995. Kapittel 26: Øian P, Henriksen T, Sviggum O. Hypertensive svangerskapskomplikasjoner. Norsk gynekologisk forening/Den norske Legeforening.

På vegne av alle medforfattere ønsker vi takke for kommentar av Jan Martin Maltau og Pål Øian på vår artikkel «En gravid kvinne i 30-årene med magesmerter, kramper og blødningssjokk». Preeklampsisyndromet har mange ansikter, der forskjellige gravide kan ha ulike tegn på det omfattende kliniske syndrombildet. Proteinuri er ikke alltid til stede verken ved HELLP-syndrom, eklampsi eller preeklampsi. Dette er nå også godt reflektert i de kliniske definisjonene av preeklampsi i norske og internasjonale veilederne i fødselshjelp og kvinnesykdommer. Vi merker oss kommentaren om at kasuistikken illustrerer hvor viktig det er med både klinisk undersøkelse og blodprøver samme dag som en gravid i siste halvdel av graviditeten rapporterer om kvalme og oppkast. Dette vil alltid være en utfordring, da veldig mange gravide har slike symptomer. Ideelt bør alle tas inn til kontroll samme dag, men vi tror dessverre ikke alltid det vil være mulig. I dette tilfellet oppfattet ikke jordmor som tok telefonen at symptomene som ble beskrevet ga så stor grunn til uro at øyeblikkelig undersøkelse var nødvendig. I etterpåklokskapens lys er det lett å tenke at kontroll dagen før innleggelse kunne avdekket patolog hos vår pasient, med påfølgende forløsning som kunne hindret katastrofen. Dette blir likevel spekulasjoner, og om andre valg i en kort telefonsamtale kunne endret noe vil aldri kunne bli besvart.