Endometriosis, adenomyosis and related health problems among women in Norway

Main findings

A total of 27,773 women (1.5 %) were registered with a diagnosis of endometriosis and 5432 (0.3 %) with adenomyosis, of whom 3029 (0.2 %) were registered with both conditions in the period 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2021.

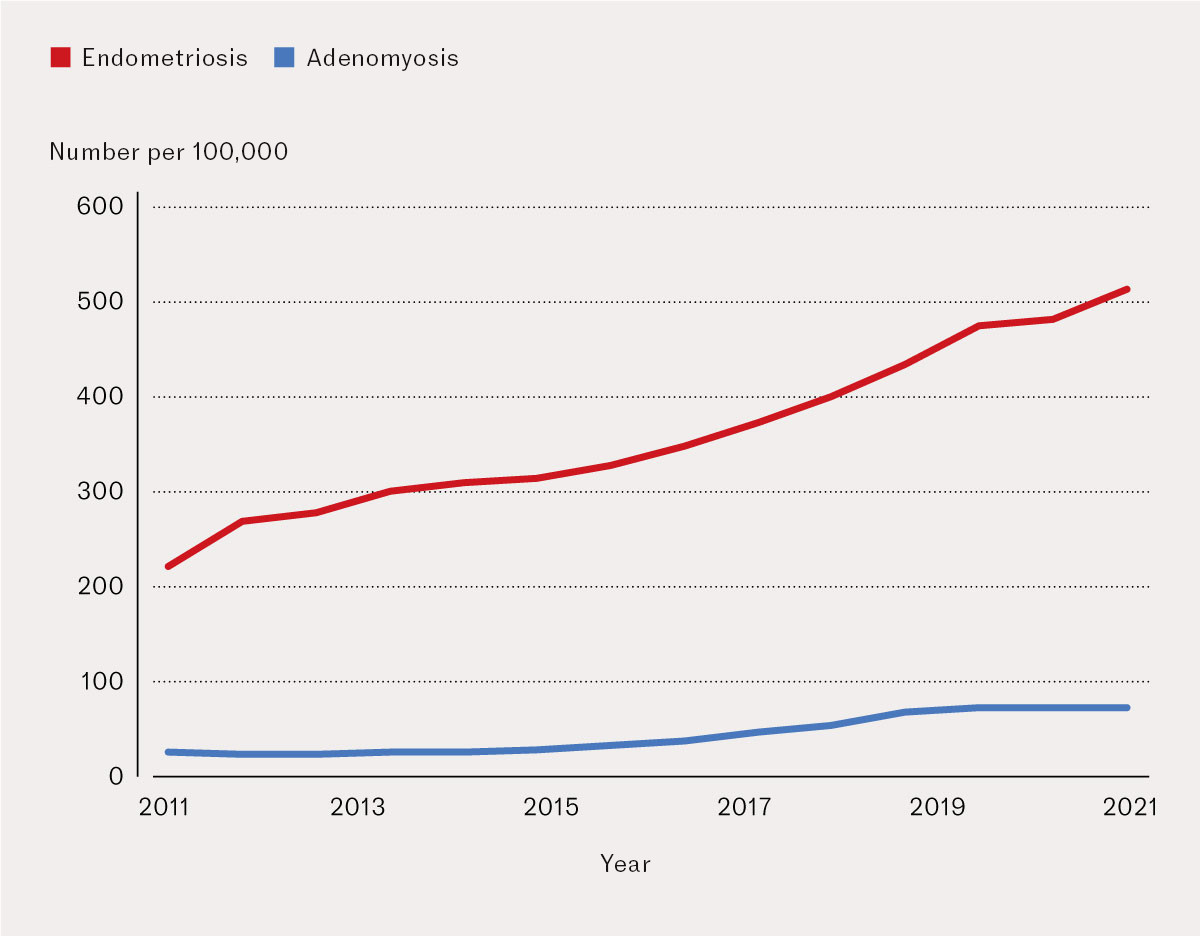

The rate of endometriosis registrations increased from 222 to 513 per 100,000 in the period 2008–2021. The corresponding figure for adenomyosis increased from 25 to 72 per 100,000 in the same period.

Endometriosis is characterised by the presence of endometrium-like tissue outside the uterus, most often on or around the ovaries and fallopian tubes or other intraperitoneal organs and surfaces, although it can also occur in the lungs or diaphragm (1). Adenomyosis entails the presence of endometrium-like tissue within the myometrium (2). Endometriosis and adenomyosis are two distinct conditions, but they are closely related, and some women have both (3). Common symptoms of these conditions include dysmenorrhea (menstrual pain), menorrhagia (heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding) and dyspareunia (pain during intercourse) (1, 2). Chronic pelvic pain and increased fatigue are also symptoms in both conditions, while dyschezia (painful defecation) and dysuria (painful urination) are more closely linked to endometriosis than to adenomyosis (1, 2). Both endometriosis and adenomyosis increase the risk of infertility (4, 5). These conditions therefore have a significant impact on women's quality of life (1, 2).

Estimating the prevalence of endometriosis and adenomyosis in the general population is challenging. This is due to the weak correlation between symptom severity and disease extent, the heterogeneous symptom profiles and the fact that a definitive diagnosis of endometriosis has historically required a biopsy via laparoscopy, while adenomyosis can be diagnosed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transvaginal ultrasound (1, 2). These factors contribute to delayed diagnosis and likely underdiagnosis (1, 2). Lifetime prevalence of endometriosis is estimated to be around 10 %, but estimates vary widely (1). Among asymptomatic women undergoing laparoscopic sterilisation, estimates range from 2–43 % (6–9); among infertile women, 5–50 % (10–14); and among hospital in-patients admitted for pelvic pain, 5–21 % (10–14). For adenomyosis, estimated prevalence among women who have undergone hysterectomy ranges from 9 to 62 % (2). Studies of adenomyosis among all women referred for transvaginal ultrasound for various reasons have estimated the prevalence to be between 21 and 34 % (15–17).

Norwegian estimates are uncertain and incomplete, but a study of 4034 women aged 40–42 living in the former county of Sør-Trøndelag estimated the lifetime prevalence of endometriosis to be 2.2 %, based on women's self-reported diagnoses (8). Data from the Health Atlas also indicate substantial geographic variation in the number of surgical procedures performed for endometriosis across Norway, with hospitals in Vestfold and Oslo particularly prominent (18). To improve understanding of the prevalence of endometriosis and adenomyosis in Norway, we obtained data from health registries on women aged 15–49 who were diagnosed with endometriosis or adenomyosis in the specialist health service in the period 2008–2021. We also collected information on the most common health problems associated with these conditions in primary care and the specialist health service in Norway, in order to examine the proportion of women with and without endometriosis or adenomyosis who were registered with these conditions.

Material and method

This study was limited to women aged 15–49 who were registered in Norway's National Population Register in the period 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2021 – a total of 1,910,661 women. For each calendar year, women aged 15–49 in that year were included. We used records from the specialist health service in the Norwegian Patient Registry (NPR) with ICD-10 codes N801–N809 (endometriosis of the ovary, fallopian tube, pelvic peritoneum, rectovaginal septum, vagina, intestine, scar tissue, or other/unspecified sites) to classify endometriosis, and N800 (endometriosis of the uterus) for adenomyosis.

From primary care, we used records of related health problems from the Norwegian Control and Payment of Health Reimbursements Database (KUHR), coded according to the ICPC-2 system. We included records of dysmenorrhea (X02), dyspareunia (X04) and menorrhagia (X06). Corresponding records of dysmenorrhea (N944–N946), menorrhagia (N920 and N921) and dyspareunia (N941) in the specialist health service according to ICD-10 codes were obtained from the Norwegian Patient Registry. Information from the different registers was merged using national personal identification numbers (PINs). In the data provided for the research project, PINs were replaced with a unique study ID.

Analyses

Results are presented as frequencies and percentages. We describe the number of unique women with at least one registration of endometriosis or adenomyosis during the entire study period, as well as the number of unique women registered with these conditions in each calendar year. Women with records in multiple years were counted in all relevant years. The total number of registrations was also calculated for each age group. In addition, we estimated the number of women with and without adenomyosis or endometriosis who were also registered with related symptoms in primary care and the specialist health service. To estimate the number of women with first-time registrations of endometriosis codes, we excluded all women with this diagnosis in the Norwegian Patient Registry up to 2010. We then calculated the incidence of first-time registrations from 2011 onward per 100,000 women aged 15–49. All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 17 (StataCorp, Texas).

Ethics

The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics approved this project (REK 2014/404), and a data protection impact assessment was conducted. All data for the research project were stored at Services for Sensitive Data (TSD) at the University of Oslo.

Results

A total of 1,910,661 women aged 15–49 were registered in Norway's National Population Register during the study period. Of these, 27,773 (1.5 %) were registered with endometriosis and 5432 (0.3 %) with adenomyosis in the specialist health service at least once. Both conditions were registered in 3029 women (0.2 %).

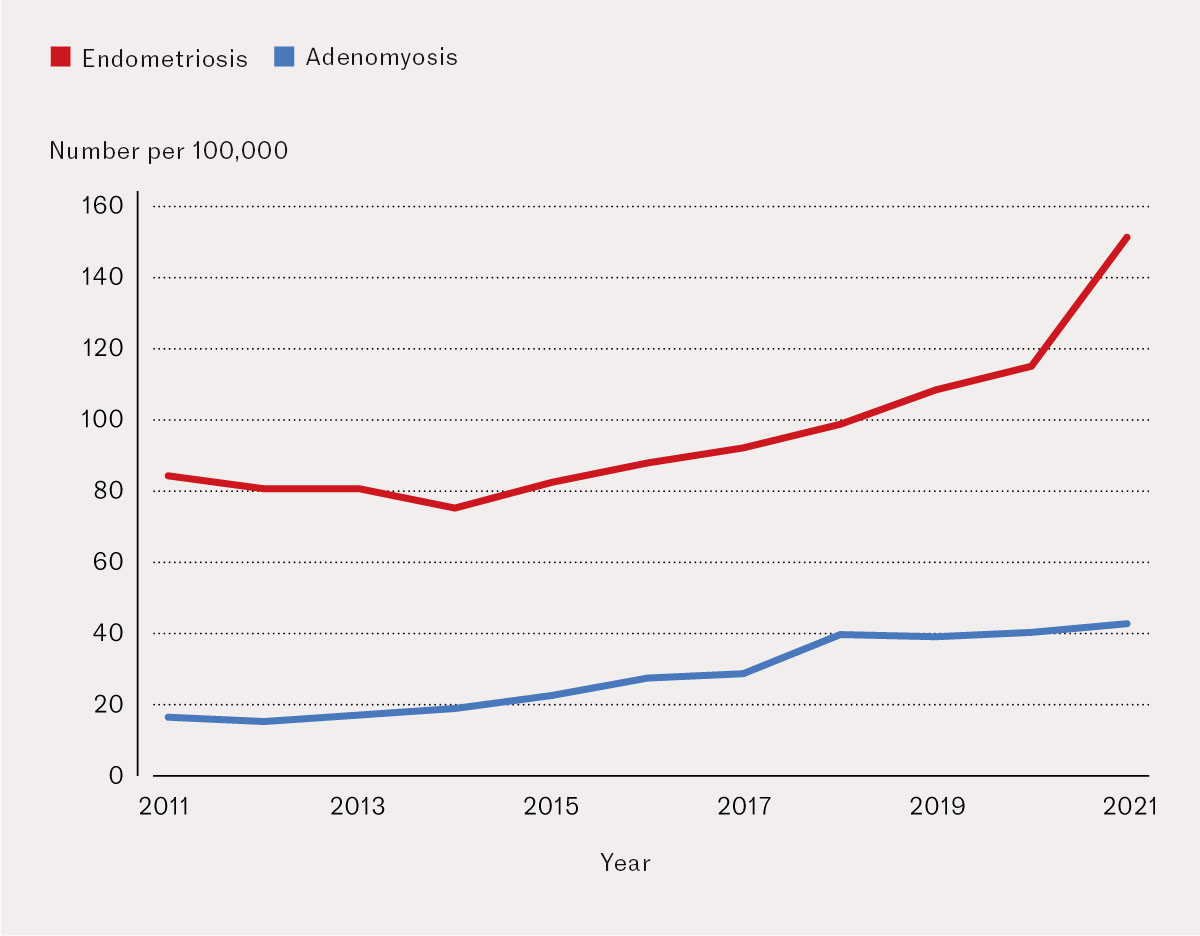

The rate of women registered with a diagnosis of endometriosis increased from 222 per 100,000 in 2008 to 513 per 100,000 in 2021, while the corresponding figure for adenomyosis increased from 25 to 72 per 100,000. Figure 1 shows the annual rate of women registered in the specialist health service with these conditions, with each woman counted only once per calendar year. Among women with at least one of the conditions, the median number of registered diagnoses was 2 (interquartile range: 1–5) over the entire study period. Between 2011 and 2021, the rate of presumed first-time registration increased from 85 to 152 per 100,000 for endometriosis and from 17 to 42 per 100,000 for adenomyosis (Figure 2).

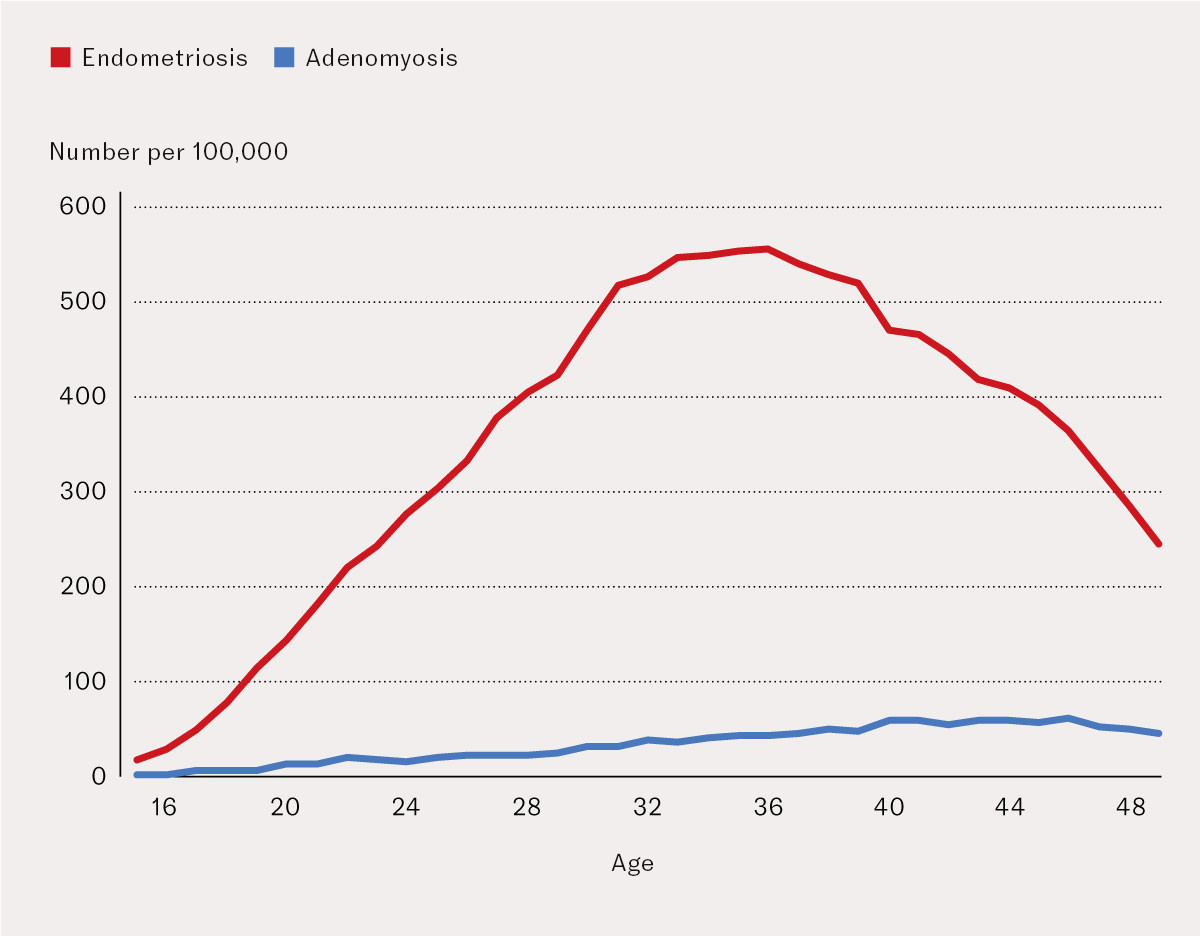

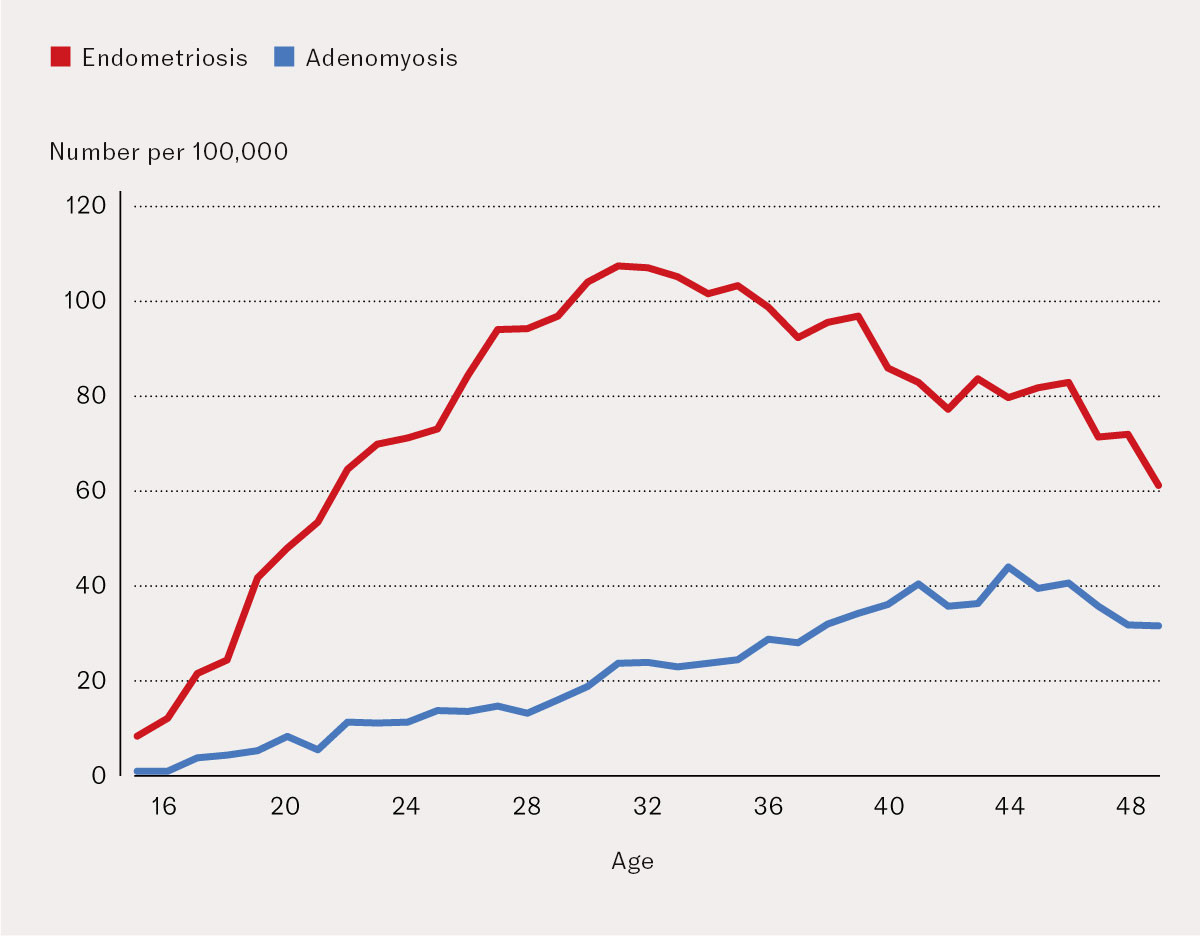

The mean age at registration was 34 years (standard deviation: 7) for endometriosis and 37 years (standard deviation: 8) for adenomyosis. Figure 3 shows the rate for each age group for both conditions. Registrations of endometriosis peaked earlier than for adenomyosis, at 36 and 44 years, respectively. The rate of presumed first-time registration of the conditions (including only women with their first registration after 2011) was highest at age 32 for endometriosis (107 per 100,000) and 44 for adenomyosis (44 per 100,000) (Figure 4).

During the study period, a total of 194,813 women aged 15–49 were registered at least once with health problems related to endometriosis and adenomyosis (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia and menorrhagia) in primary care. The corresponding figure in the specialist health service was 174,165. Table 1 shows the prevalence of the three symptoms among women with endometriosis or adenomyosis. The prevalence of all related health problems in both primary care and the specialist health service was higher among women with endometriosis or adenomyosis than among women with no registrations for these conditions (Table 1). For example, the proportion of women with dysmenorrhea registered in primary care was 21 % among those with endometriosis and 22 % among those with adenomyosis, compared with 4.5 % among women without these conditions registered in the specialist health service. Twelve per cent of women with endometriosis were registered with menorrhagia in primary care, compared with 19 % of those with adenomyosis and only 5 % of women without these conditions. Women registered with both endometriosis and adenomyosis had an even higher frequency of related health problems in primary care. Similar figures were observed for symptoms in the specialist health service.

Table 1

Number of women aged 15–49 registered in the specialist health service (records in the Norwegian Patient Registry (NPR)) with diagnoses of endometriosis and adenomyosis and main symptoms registered in primary care (records in the Norwegian Control and Payment of Health Reimbursements Database (KUHR)) in the period 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2021.

| Sector | Symptom | Endometriosis (n = 27 773) | Adenomyosis (n = 5 432) | Endometriosis and adenomyosis (n = 3 029) | Neither endometriosis nor adenomyosis (n = 1 880 485) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | Dysmenorrhea | 5 715 (20.6) | 1 202 (22.1) | 784 (25.9) | 83 686 (4.5) |

| Dyspareunia | 1 277 (4.6) | 254 (4.7) | 157 (5.2) | 2 461 (0.1) | |

| Menorrhagia | 3 387 (12.2) | 1 048 (19.3) | 484 (16.0) | 90 918 (4.8) | |

| Specialist health service | Dysmenorrhea | 7 062 (25.4) | 1 785 (32.9) | 1 271 (42.0) | 34 080 (1.8) |

| Dyspareunia | 2 377 (8.6) | 560 (10.3) | 372 (12.3) | 29 226 (1.6) | |

| Menorrhagia | 5 362 (19.3) | 2 045 (37.6) | 1 030 (34.0) | 112 739 (6.0) |

Discussion

We found that 1.5 % of women aged 15–49 in Norway were registered with a diagnosis of endometriosis in the specialist health service during the period 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2021. For adenomyosis, the prevalence was 0.3 %, while 0.2 % were registered with both conditions. The rate of registrations for endometriosis and adenomyosis increased in Norway between 2008 and 2021. This may have been partly due to the increased media focus on both endometriosis and adenomyosis, potentially leading more women to seek medical evaluation. Women with a diagnosis prior to 2008 and no subsequent registrations for the conditions would not have been identified with the conditions in our study. It is therefore difficult to make direct comparisons with estimates from previous studies.

In interpreting these results, it is important to consider that there are different reasons why some women are registered by the specialist health service and others are not. This may be where they first sought evaluation, diagnosis and possible treatment for problems related to symptoms of endometriosis and/or adenomyosis. In some cases, women may only be diagnosed after experiencing difficulties conceiving, as the prevalence of infertility is high among these women. Further investigation then reveals that endometriosis and/or adenomyosis has potentially contributed to the fertility problems (4, 5). This aligns with the observation that registrations peaked at age 34 for endometriosis and 37 for adenomyosis. Many women in their late thirties seek help for fertility issues and consider Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART), which may increase the number diagnosed with endometriosis or adenomyosis in this age group. It is also possible that these conditions are first identified during laparoscopy or hysterectomy performed for other reasons, without endometriosis or adenomyosis initially being suspected, such as during treatment for cancer or other conditions (19–21). We do not know whether the diagnoses were based on laparoscopy and histology, imaging, symptoms, or by ruling out other causes.

We have presented the number and proportion of women with registered symptoms related to endometriosis and adenomyosis in primary care (2, 22). There are no reliable population-based estimates of the prevalence of the symptoms we studied. Some studies specifically describe menstrual disorders among adolescents, sportswomen or women approaching menopause, and these have been further summarised in meta-analyses (23–25). We found that the proportion of women registered with the various symptoms was two to four times higher among those with endometriosis or adenomyosis compared to those without, and that the prevalence of menorrhagia was higher for adenomyosis than endometriosis.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to describe patient contact relating to endometriosis and adenomyosis in the specialist health service in Norway. The population-based data from Norway's central health registries provide a unique opportunity to include information from the entire Norwegian population. One limitation of the registries is that it was not possible to identify women diagnosed prior to the inclusion of individual-level data. This likely applies primarily to women who were 35 years or older in 2008, particularly those diagnosed before 2008 who had no contact with or diagnosis from the specialist health service for these conditions during the study period. It is not therefore possible to calculate lifetime prevalence among women using this dataset.

There was a marked increase in the number of registered diagnoses from 2011 to 2021. Estimating the incidence of endometriosis is challenging, as the Norwegian Patient Registry does not contain individual-level diagnosis data before 2008, and women diagnosed prior to 2008 may not have had any subsequent registrations after that year. In addition to the difficulty of establishing the diagnosis, awareness of these conditions has also increased over time. The observed increase in registered diagnoses likely does not represent a true rise in the prevalence of the condition and should not therefore be interpreted as an increase in incidence. Furthermore, estimating the incidence of endometriosis and adenomyosis is particularly challenging due to the long interval between symptom onset and diagnosis, as well as advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of these conditions. The estimates we present must therefore be interpreted in light of these factors. Despite increased awareness of the conditions, the extent of underdiagnosis in Norway remains unknown, particularly because of the poor correlation between perceived symptoms and objective findings. Such investigations would be valuable in smaller population-based studies of randomly selected women, and could potentially be conducted on a larger scale as less invasive diagnostic methods are gradually adopted. The quality of registry data no doubt varies, particularly in relation to symptom codes in primary care, as these largely depend on the clinician's experience and clinical judgement.

Conclusion

Using data from the Norwegian Patient Registry, we found that approximately 2 % of women aged 15–49 were registered with endometriosis or adenomyosis in the specialist health service between 2008 and 2021. This is likely an underestimation, as women in older age groups may have received their diagnosis before the registry was established. It is also generally assumed that these conditions are underdiagnosed. There was a clear increase in the number of women registered in the specialist health service with these two conditions during the study period. In addition to a possible real increase in prevalence, our findings may also reflect growing awareness of these conditions in the population. This may be related to increased media attention, improved diagnostics with MRI and ultrasound, changing diagnostic principles, new medications and better surgical treatment options.

The study was funded by the Research Council of Norway (project numbers 262700, 351058 and 320656).

The article has been peer-reviewed

- 1.

As-Sanie S, Mackenzie SC, Morrison L et al. Endometriosis: A Review. JAMA 2025; 334: 64–78. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

Upson K, Missmer SA. Epidemiology of Adenomyosis. Semin Reprod Med 2020; 38: 89–107. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Donnez J, Stratopoulou CA, Dolmans MM. Endometriosis and adenomyosis: Similarities and differences. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2024; 92. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2023.102432. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Mishra I, Melo P, Easter C et al. Prevalence of adenomyosis in women with subfertility: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2023; 62: 23–41. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Namazi M, Behboodi Moghadam Z, Zareiyan A et al. Impact of endometriosis on reproductive health: an integrative review. J Obstet Gynaecol 2021; 41: 1183–91. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

ENDO Study Working Group. Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil Steril 2011; 96: 360–5. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Flores I, Abreu S, Abac S et al. Self-reported prevalence of endometriosis and its symptoms among Puerto Rican women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008; 100: 257–61. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Moen MH, Schei B. Epidemiology of endometriosis in a Norwegian county. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997; 76: 559–62. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Strathy JH, Molgaard CA, Coulam CB et al. Endometriosis and infertility: a laparoscopic study of endometriosis among fertile and infertile women. Fertil Steril 1982; 38: 667–72. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Duignan NM, Jordan JA, Coughlan BM et al. One thousand consecutive cases of diagnostic laparoscopy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1972; 79: 1016–24. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Hasson HM. Incidence of endometriosis in diagnostic laparoscopy. J Reprod Med 1976; 16: 135–8. [PubMed]

- 12.

Kleppinger RK. One thousand laparoscopies at a community hospital. J Reprod Med 1974; 13: 13–20. [PubMed]

- 13.

Liston WA, Bradford WP, Downie J et al. Laparoscopy in a general gynecologic unit. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1972; 113: 672–7. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Meuleman C, Vandenabeele B, Fieuws S et al. High prevalence of endometriosis in infertile women with normal ovulation and normospermic partners. Fertil Steril 2009; 92: 68–74. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Naftalin J, Hoo W, Nunes N et al. Association between ultrasound features of adenomyosis and severity of menstrual pain. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016; 47: 779–83. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Naftalin J, Hoo W, Pateman K et al. How common is adenomyosis? A prospective study of prevalence using transvaginal ultrasound in a gynaecology clinic. Hum Reprod 2012; 27: 3432–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 17.

Pinzauti S, Lazzeri L, Tosti C et al. Transvaginal sonographic features of diffuse adenomyosis in 18-30-year-old nulligravid women without endometriosis: association with symptoms. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015; 46: 730–6. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 18.

Senter for klinisk dokumentasjon og evaluering. Kirurgiske inngrep for endometriose. https://analyser.skde.no/no/analyse/endometriose/ Accessed 28.2.2025.

- 19.

Kvaskoff M, Mahamat-Saleh Y, Farland LV et al. Endometriosis and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2021; 27: 393–420. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Li J, Liu R, Tang S et al. Impact of endometriosis on risk of ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancers: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019; 299: 35–46. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 21.

Yuan H, Zhang S. Malignant transformation of adenomyosis: literature review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019; 299: 47–53. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 22.

Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1244–56. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Monteleone P, Mascagni G, Giannini A et al. Symptoms of menopause - global prevalence, physiology and implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018; 14: 199–215. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 24.

Pouraliroudbaneh S, Marino J, Riggs E et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea in adolescents: A systematic review of self-management strategies, quality of life, and unmet needs. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2024; 167: 16–41. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 25.

Taim BC, Ó Catháin C, Renard M et al. The Prevalence of Menstrual Cycle Disorders and Menstrual Cycle-Related Symptoms in Female Athletes: A Systematic Literature Review. Sports Med 2023; 53: 1963–84. [PubMed][CrossRef]