Use of psychotropic medications in the specialist health service for mental health care and substance use disorders in 2012–23

Mental disorders are one of the greatest health and societal challenges in Norway. Considerable resources are used in the treatment of mental disorders, and the Norwegian National Health and Hospital Plan 2020–2023 has focused on the further development of mental health services, including through the utilisation of health data (1). Psychotropic medications are used as part of the treatment for several mental disorders.

In Norway, there are three national databases for medication consumption: the Norwegian Drug Wholesale Statistics, the Norwegian Prescribed Drug Registry and the Hospital Pharmacies Drug Statistics (2). Statistics on medication use are important from a public health perspective and can help promote optimal prescription of medications (3). Figures from the Hospital Pharmacies Drug Statistics are used actively as a management tool for the use of antibiotics in health trusts (4). Data from hospitals on medication use are valuable for assessing clinical practice, including undesirable variation, work on therapeutic guidelines and hospital economics.

Figures on the use of psychotropic medication in psychiatric hospitals in the 1990s were published in 2003 (5) and figures for the period 2001–10 were published in 2015 (6). Recent published material on the use of psychotropic medications in the general population are based on figures from the Norwegian Prescribed Drug Registry (7–12). There is, therefore, a need for an update following the many changes in treatment services within mental health care and interdisciplinary specialised treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs) over the past 10 years.

The objective of the study is to increase knowledge on the use of anxiolytics, antidepressants, mood stabilisers and antipsychotics in the period 2012–23 in specialist mental health services and interdisciplinary specialised SUD treatment.

Material and method

The study is a drug utilisation study based on purchasing data from the Hospital Pharmacies Drug Statistics for the period 2012–23. The analysis is limited to clinics in the specialist mental health service and interdisciplinary specialised SUD treatment in public hospitals and private hospitals run by non-profit organisations. Bed-days are based on Tables 13942, 06922 and 04511 from Statistics Norway (13–15).

Psychotropic groups and medications are specified in Table 1. Medications with and without marketing authorisation in Norway are included. The various medication groups are classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. Defined daily doses (DDD), which represent the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a medication used for its main indication in adults, are compared across a range of package sizes, strengths and active ingredients (16).

Table 1

Overview of included medication groups and medications

| Group | ATC Codes |

|---|---|

| Anxiolytics | N03AE01 clonazepam, N05BA01 diazepam, N05BA04 oxazepam, N05BA06 lorazepam, N05BA12 alprazolam |

| Antidepressants | N06A** - all active ingredients |

| Mood stabilisers | N03AF01 carbamazepine, N03AF02 oxcarbazepine, N03AG01 valproic acid, N03AX09 lamotrigine, N03AX14 levetiracetam, N05AN01 lithium |

| Antipsychotics | N05A**- all active ingredients excluding N05AN01 lithium |

'Mood stabiliser' is an umbrella term for medications that can be efficacious in the treatment of depression and mania/hypomania, and which can prevent future affective episodes (17). The mood stabiliser category includes lithium, a purely mood-stabilising medication, as well as antipsychotics and antiepileptics. Based on the guidelines for treatment (18, 19) and clinical practice, lithium and the antiepileptics lamotrigine, valproic acid, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine and levetiracetam are included. Antipsychotics are analysed in a separate main group. Use in terms of number of defined daily doses (DDD)/100 bed-days, percentage change and simple linear regression analysis was calculated using Microsoft Excel 365. The data are anonymous and there is no requirement for specific approval of the study.

Results

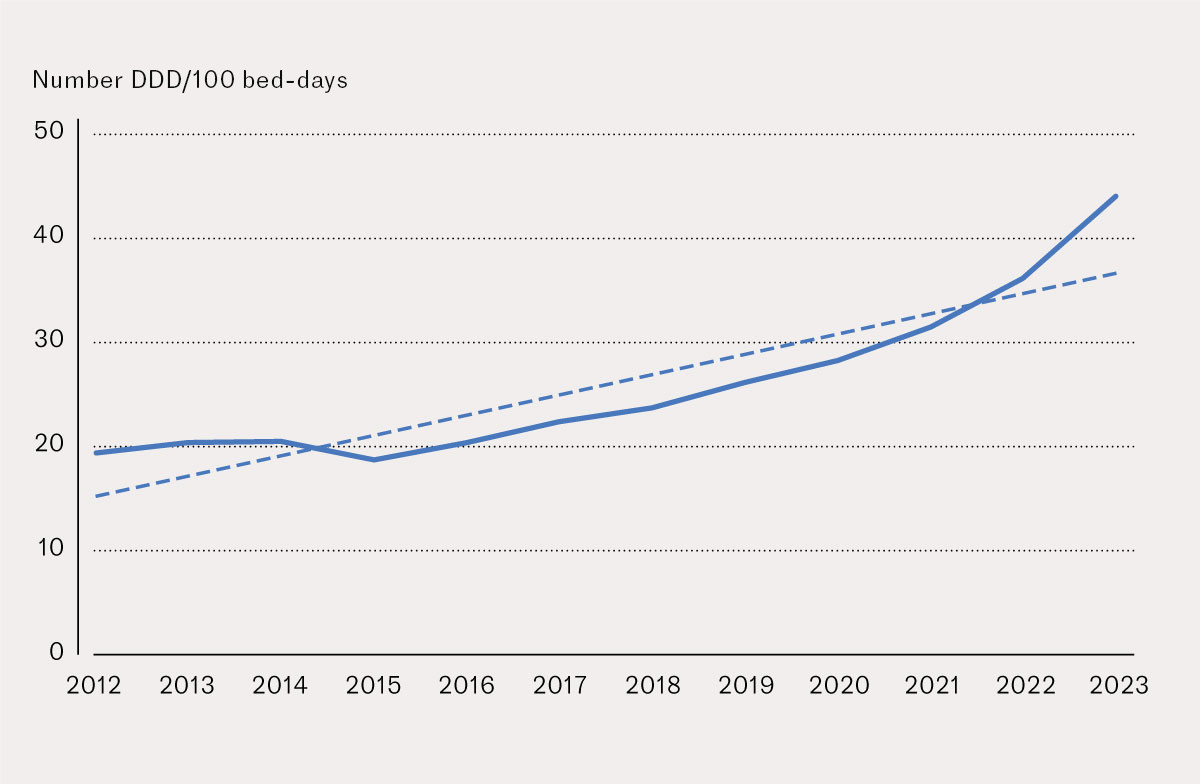

Use of anxiolytics rose by 127 % from 2012 to 2023 (Figure 1), with an estimated growth of 1.95 DDD/100 bed-days per annum. The increased administration of diazepam accounts for the main part of this growth (Table 2). In 2023, diazepam constituted 67 % of use. Use of lorazepam rose by 283 % during the reference period (Table 2), but only constituted 8 % of anxiolytics in 2023.

Table 2

The five most used medications in each group in 2023 and the percentage change from 2012 to 2023. DDD: Defined daily dose. B-D: Bed-days.

| Medication groups | Medication (ATC code) | DDD/100 B-D 2023 | Change (%) from 2012 to 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants | Sertraline (N06AB06) | 9.8 | 28 |

| Venlafaxine (N06AX16) | 7.0 | -24 | |

| Mirtazapine (N06AX11) | 6.9 | -11 | |

| Escitalopram (N06AB10) | 6.9 | -52 | |

| Fluoxetine (N06AB03) | 2.7 | -39 | |

| Antipsychotics peroral administration | Olanzapine (N05AH03) | 23.6 | 11 |

| Quetiapine (N05AH04) | 8.6 | -38 | |

| Clozapine (N05AH02) | 5.8 | -9 | |

| Aripiprazole (N05AX12) | 5.7 | 3 | |

| Risperidone (N05AX08) | 2.5 | -2 | |

| Antipsychotics depot injections | Olanzapine (N05AH03) | 29.0 | 123 |

| Paliperidone (N05AX13) | 21.0 | 118 | |

| Aripiprazole (N05AX12) | 13.9 | UNDEF1 | |

| Zuclopenthixol (N05AF05) | 10.0 | 28 | |

| Perphenazine (N05AB03) | 4.2 | -45 | |

| Anxiolytics | Diazepam (N05BA01) | 29.5 | 281 |

| Oxazepam (N05BA04) | 10.1 | 21 | |

| Lorazepam (N05BA06) | 3.5 | 283 | |

| Alprazolam (N05BA12) | 0.8 | -46 | |

| Lorazepam (N03AE01) | 0.2 | -78 | |

| Mood stabilisers | Valproic acid (N03AG01) | 5.4 | -13 |

| Lithium (N05AN01) | 3.7 | -16 | |

| Lamotrigine (N03AX09) | 2.2 | -53 | |

| Levetiracetam (N03AX14) | 0.6 | 130 | |

| Carbamazepine (N03AF01) | 0.1 | -82 |

1Aripiprazole depot injections were marketed in 2014/2015. Zero consumption in 2012 means that the rate of growth is undefinable. The percentage change from 2014 is 503.

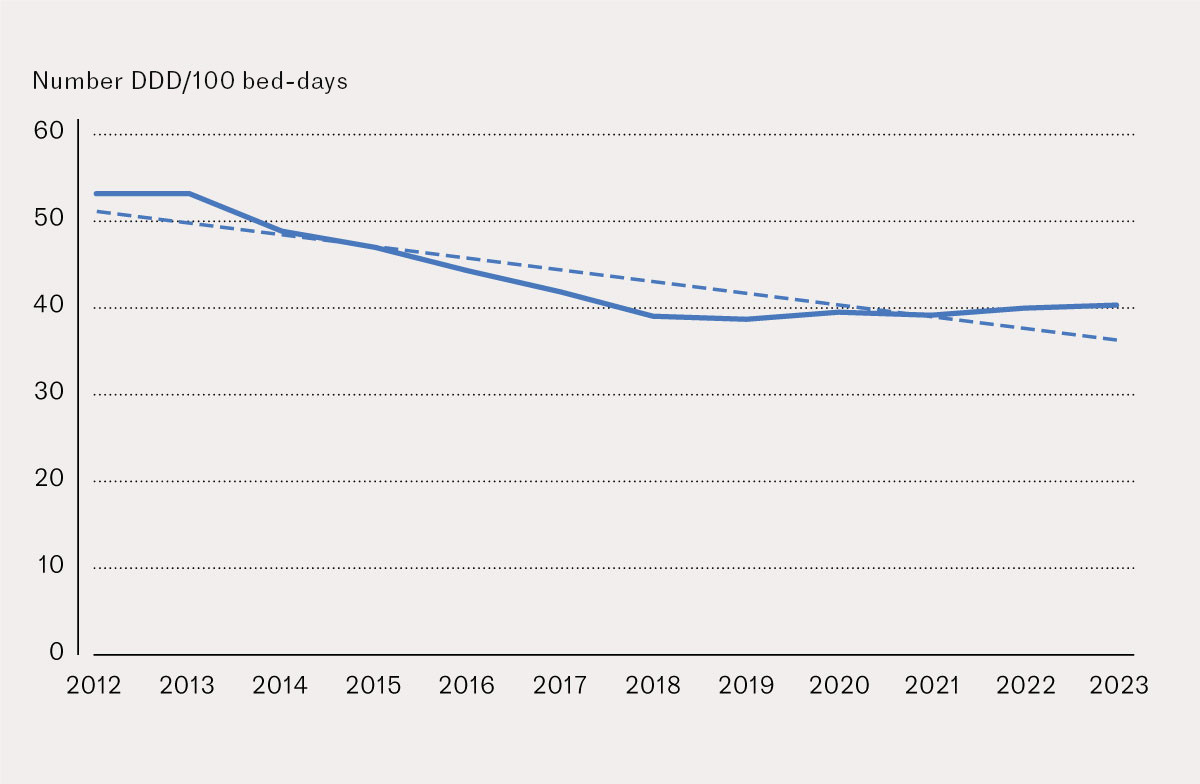

Use of antidepressants declined by 24 % from 2012 to 2023 (Figure 2). The estimated reduction in the number of DDD/100 bed-days is 1.35 per annum. The decrease in the use of escitalopram (Table 2) accounts for most of the change in the group. Of the five most used antidepressants in the period, only sertraline increased in use (Table 2).

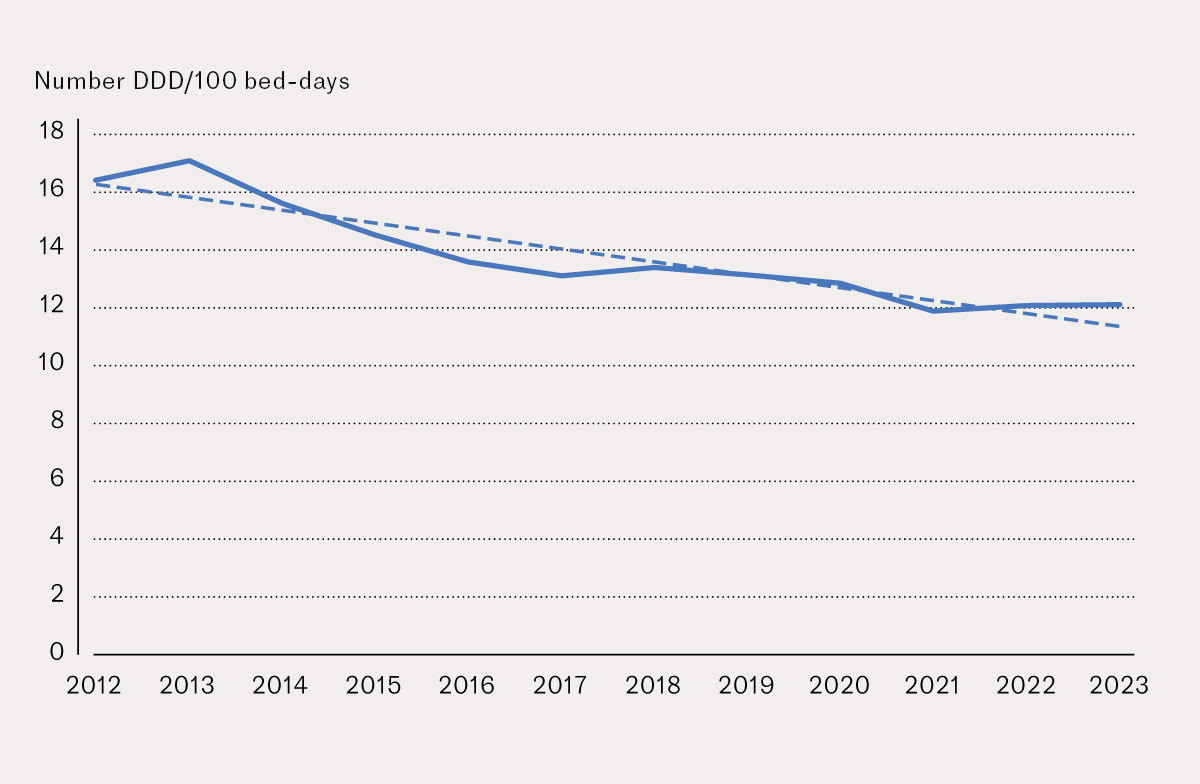

Use of mood stabilisers declined by 26 % from 2012 to 2023 (Figure 3), with an estimated reduction per annum of 0.45 DDD/100 bed-days. Use of lithium decreased by 16 %. Levetiracetam is the only medication in the group that increased, but the proportion is very small (Table 2).

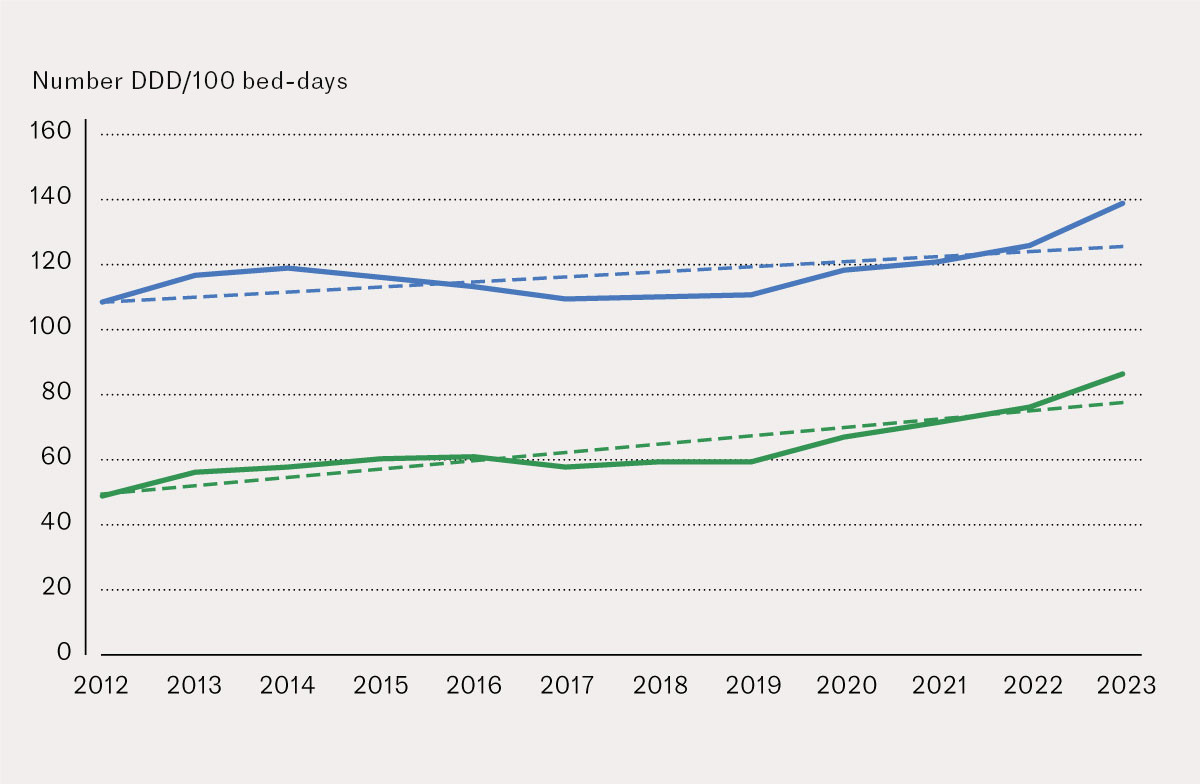

There was an increase in the total use of antipsychotics of 29 % from 2012 to 2023 (Figure 4), but this fluctuated during the period. Use of peroral antipsychotics declined by 12 % in the same period. On the whole, there was a relatively large reduction in the use of quetiapine (Table 2), but there was a 49 % increase for the low-dose 25 mg tablets. Use of depot injections rose by 79 %, from 48 to 87 DDD/100 bed-days, from 2012 to 2023 (Figure 4), with an estimated growth of 2.58 DDD/100 bed-days per annum. The percentage of depot injections increased from 45 in 2012 to 62 in 2023.

Discussion

National purchasing data for clinics offering specialist mental health services and interdisciplinary specialised SUD treatment show a significant increase in the use of anxiolytics. There has been a decline in the use of antidepressants and mood stabilisers. The antipsychotics group has increased somewhat, while the use of depot injections has grown by 79 %.

Diazepam is the most used of the anxiolytics and has shown a marked increase in recent years. The reduction in the number of beds in mental health services for adults and interdisciplinary specialised SUD treatment, combined with more outpatient clinic consultations and an increase in the number of people involuntarily admitted, may have led to a change in the composition of patients. This could mean that those currently receiving treatment as inpatients are more seriously ill than previously and may, therefore, have a greater need for sedatives (13, 20). The increase in diazepam may also be due to changes in the guidelines for opioid maintenance treatment (21), as benzodiazepines used in tapering or maintenance treatment implemented by the hospital are now paid for by the health trust. Use of prescription benzodiazepines in Norway and the Nordic region fell during the reference period (3, 7). Consequently, despite an increase in use in specialist mental health services and interdisciplinary specialised SUD treatment, it is unlikely that more patients will be discharged from the hospitals with a prescription for benzodiazepines.

A reduction has been observed in the antidepressant group while use has remained more stable in the primary health service during the same period, albeit with an increase during the pandemic 2020–22 (3, 10, 22). A decrease in the use of escitalopram, which is mostly used on prescription, and a rise in sertraline has been observed in hospitals and in the primary health service. In relation to mirtazapine, venlafaxine and fluoxetine, there has been an increase in prescriptions but a reduction in hospital use (22). A possible change in the composition of hospital patients may explain the differing consumption patterns. It cannot be ruled out that therapists in hospitals may have a more critical attitude towards the efficacy and side effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (23, 24).

The reduction in the use of mood stabilisers may be due to several factors. One possible explanation could be the decrease in admissions of patients with bipolar disorder in recent years (25, 26) or the increased use of antipsychotics as part of their treatment. Of the mood stabilisers, only lithium is used exclusively for the treatment of affective disorders. The proportion of patients using lithium on prescription per 1000 people per annum decreased from 1.6 in 2012 to 1.4 in 2021, and the age distribution changed, with a larger percentage of older people among users (3, 22). During the period of this study, lithium use decreased by 16 %. Reduced use of lithium for bipolar disorders may represent a deviation from the guidelines. A decline in lithium use has been registered in many countries and is a cause for concern as lithium is considered the best medication for bipolar disorder with regard to treating mania and preventing illness and suicide (27–30).

The proportion of antipsychotics administered in the form of depot injections increased in the period 2012–23. This may reflect the increased focus on medication adherence to prevent readmission (31), but also changes to, and the interpretation of, the legislation on the use of coercion from 2017 (32). From 2015 to 2022, there was an increase in involuntary admissions, in the proportion of patients medicated without consent, and in the number of outpatients involuntarily receiving mental health care (33). The treatment of patients in the latter group with depot injections of antipsychotics is paid for by the health trust, which may also have contributed to the observed increase.

The figures show a decline in the use of peroral antipsychotics, while antipsychotics on prescription increased in the years 2017–21 (3). The national clinical guidelines for pharmacological treatment of psychotic disorders were published recently. They recommend that second-generation antipsychotics with a low metabolic impact should be used in relation to the first episode of psychosis (34). The Danish guidelines specify aripiprazole as a first-line medication (35), while there is no specified preferred medication in the Norwegian guidelines. In a survey conducted in the Early Intervention in Psychosis Advisory Unit at Oslo University Hospital in 2022, 43 % of the patients used olanzapine and 29 % used aripiprazole (36). Our study shows that olanzapine and quetiapine are used more than aripiprazole, but that the use of depot injections of aripiprazole is increasing. A decline in clozapine use (9 %) was observed during the reference period. A study based on dispensed prescription data identified major regional variations in the prescription of clozapine in Norway. The study suggested that differences in the degree of implementation of the national guidelines were a possible cause (11). This may also be a contributory factor in the change observed in our figures. There has been a focus on the off-label use of quetiapine as a hypnotic and sedative (37, 38). Use of this medication on a 'white' prescription (usually not reimbursed) has increased in recent years (39), and our figures reveal the increased use of low-dose tablets.

Large-scale events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, may have impacted medication use. Prescriptions of antidepressants and low-dose quetiapine on prescription increased in Norway during the pandemic (22), as well as anxiolytics and hypnotics in Scandinavia (10). On the basis of this study alone, we cannot determine whether the pandemic affected the use of psychotropic medication in hospitals.

The strength of this study is the complete set of data for purchases of anxiolytics, antidepressants, mood stabilisers and antipsychotics in hospitals offering mental health services and interdisciplinary specialised SUD treatment over a 12-year period. Other available data, such as the figures from the Norwegian Drug Wholesale Statistics and the Norwegian Prescribed Drug Registry (3), reveal little about medication use in hospitals.

A limitation of the study is that the available data for medication use in Norwegian hospitals are based on purchasing figures and not, therefore, actual use by patients. Drugs purchased for a department can be administered to patients, disposed of or stored. The difference between purchase and use is primarily linked to periodisation. If longer time periods are used, from six months up to a year, purchased DDD will provide estimates that correspond to use (40). Only three European countries (Belgium, Italy and Portugal) have national databases of medication use that record what has actually been administered to patients in hospitals (41).

A range of factors, including activities, patient composition, changes to treatment guidelines, opinion leaders, legislation and purchasing agreements will have a potential impact on medication use in hospitals. An increase in the number of DDD indicates that either more patients have received the medication or that the doses have increased. We have used DDD/100 bed-days, as recommended by WHO, as an indicator to correct for activity levels in hospitals (42). Other indicators for medication use, which use bed-days, patient composition and number of inpatients, may provide a more accurate measure (43).

This study does not provide answers regarding causal relations or the effects of the observed changes; however, with a time series spanning many years, changes in the figures can be assessed in relation to concurrent events that could potentially have impacted medication use in hospitals. The study serves as a basis for hypotheses for further research. Future studies should examine the correlation between medication use and patient data, as well as assess practice in relation to guidelines. It will be relevant to compare medication use between different units within the mental health service and interdisciplinary specialised SUD treatment with the Helseatlas [Health Atlas] study, which reports undesirable variations in the treatment provision (44). Regular reporting of psychotropic medication use on a national, regional and local level will be able to provide an overview that helps to optimise medication use in hospitals.

We would like to thank Martin Isaksen and Fredrik Hjorth Bentsen (Hospital Pharmacies Drug Statistics) for their data quality assurance and statistical assistance, and senior consultant Morten Juell (Innlandet Hospital Trust) for insightful discussions.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Helse- og Omsorgsdepartementet. Nasjonal helse- og sykehusplan 2020-2023. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nasjonal-helse--og-sykehusplan-2020-2023/id2679013/ Accessed 14.1.2023.

- 2.

Sommerschild HT, Berg CL, Jonasson C et al. Data resource profile: Norwegian Databases for Drug Utilization and Pharmacoepidemiology. Nor Epidemiol 2021; 29: 7–12. [CrossRef]

- 3.

Folkehelseinstituttet. Legemiddelstatistikk 2022. Legemiddelforbruket i Norge 2017-2021 - Data fra Grossistbasert legemiddelstatistikk og Reseptregisteret. https://www.fhi.no/publ/2022/legemiddelforbruket-i-norge--20172021-data-fra-grossistbasert-legemiddelsta/ Accessed 12.10.2022.

- 4.

NIPH. NORM/NORM-VET. Usage of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Norway. https:// www.fhi.no/en/publ/2023/norm-og-norm-vet-usage-of-antimicrobial-agents-and-occurrence-of-antimicrobial-resistance-in-norway/ Accessed 28.11.2023.

- 5.

Rytter E, Håberg M. Forbruk av psykofarmaka ved psykiatriske sykehus i Norge 1991-2000. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2003; 123: 768–71. [PubMed]

- 6.

Løken GØ, Hynnekleiv T. Forbruk av psykofarmaka ved norske psykiatriske sykehus, med særlig fokus på Sykehuset Innlandet. En registerstudie fra perioden 2001-2010, sammenlignet med foregående tiår. 2015 https://sihf.brage.unit.no/sihf-xmlui/handle/11250/3120577 Accessed 17.3.2023.

- 7.

Højlund M, Gudmundsson LS, Andersen JH et al. Use of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drugs in the Nordic countries between 2000 and 2020. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2023; 132: 60–70. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Højlund M, Pottegård A, Johnsen E et al. Trends in utilization and dosing of antipsychotic drugs in Scandinavia: Comparison of 2006 and 2016. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2019; 85: 1598–606. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Ruths S, Haukenes I, Hetlevik Ø et al. Trends in treatment for patients with depression in general practice in Norway, 2009-2015: nationwide registry-based cohort study (The Norwegian GP-DEP Study). BMC Health Serv Res 2021; 21: 697. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Tiger M, Wesselhoeft R, Karlsson P et al. Utilization of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Scandinavia. J Affect Disord 2023; 323: 292–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Schou MB, Drange OK, Sæther SG. Fylkesvise forskjeller i forskrivning av klozapin. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2019; 139: 1265–70.

- 12.

Tveito M, Handal M, Engedal K et al. Forskrivning av antipsykotika til hjemmeboende eldre 2006–18. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2019; 139. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.19.0233. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Statistisk Sentralbyrå. Aktivitet, kapasitet og beleggsprosent i spesialisthelsetjenesten, etter tjenesteområde og helseforetak 2015-2023. Tabell 13942. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/13942/ Accessed 26.6.2024.

- 14.

Statistisk Sentralbyrå. Psykisk helsevern for voksne. Døgnplasser, utskrivninger, oppholdsdøgn, polikliniske konsultasjoner og oppholdsdager, etter helseforetak (avslutta serie) 1990 - 2021. Tabell 04511. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/04511/ Accessed 26.6.2024.

- 15.

Statistisk Sentralbyrå. Aktivitet og døgnplasser i spesialisthelsetjenesten, etter tjenesteområde og helseforetak (avslutta serie) 2002 - 2021. Tabell 06922. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/06922 Accessed 26.6.2024.

- 16.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2022. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ Accessed 5.5.2023.

- 17.

Metodebok.no. Stemningsstabiliserende legemidler, Psykofarmaka/annen behandling, Akuttpsykiatri - VAP (AHUS/SØ). https://metodebok.no/index.php?action=topic&item=pRwJXAKt Accessed 19.8.2023.

- 18.

Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonal fagleg retningslinje for utgreiing og behandling av bipolare lidingar. IS-1925. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/bipolare-lidingar/Bipolare%20lidingar%20%E2%80%93%20Nasjonal%20faglig%20retningslinje%20for%20utgreiing%20og%20behandling.pdf/_/attachment/inline/0a495dbf-91ed-4049-90c6-cb46f5babcda:b01d1720e1996ad7b30e8a4f5d4fe522b35265e1/Bipolare%20lidingar%20%E2%80%93%20Nasjonal%20faglig%20retningslinje%20for%20utgreiing%20og%20behandling.pdf Accessed 17.11.2022.

- 19.

UpToDate. Bipolar disorder in adults: Choosing maintenance treatment [database].; Tilgjengelig fra: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bipolar-disorder-in-adults-choosing-maintenance-treatment?search=bipolar%20treatment&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H9625303 Accessed 21.8.2023.

- 20.

Helsedirektoratet. Samdata Spesialisthelsetjenesten. Tvunget psykisk helsevern med døgnopphold. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/statistikk/samdata-spesialisthelsetjenesten/psykisk-helsevern-tvungent-psykisk-helsevern-med-dognopphold Accessed 13.1.2024.

- 21.

Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for legemiddelassistert rehabilitering (LAR) ved opioidavhengighet. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/behandling-ved-opioidavhengighet Accessed 29.10.2023.

- 22.

Folkehelseinstituttet. Legemiddelregisteret (NorPD). https://www.reseptregisteret.no/ Accessed 2.4.2025.

- 23.

Jakobsen JC, Katakam KK, Schou A et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus placebo in patients with major depressive disorder. A systematic review with meta-analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017; 17: 58. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 24.

Vaaler AE, Fasmer OB. Antidepressive legemidler - klinisk praksis må endres. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2013; 133: 428–30. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 25.

Folkehelseinstituttet. Aktivitetsdata for spesialisthelsetjenesten. Psykisk helsevern for voksne, årsdata 2023. https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/2024/aktivitet-phv-2023---spesialisthelsetjenesten.pdf Accessed 22.4.2024.

- 26.

Helsedireketoratet. Aktivitetsdata for psykisk helsevern for voksne og tverrfaglig spesialisert rusbehandling 2019. IS-2893. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/17839cfed7ff4d899add2bf4ad71442f/aktivitet-i-psykisk-helsevern-for-voksne-og-tverrfaglig-spesialisert-rusbehandling-2019.pdf Accessed 22.4.2024.

- 27.

Malhi GS, Bell E, Hamilton A et al. Lithium mythology. Bipolar Disord 2021; 23: 7–10. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 28.

Malhi GS, Bell E, Jadidi M et al. Countering the declining use of lithium therapy: a call to arms. Int J Bipolar Disord 2023; 11: 30. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 29.

Lyall LM, Penades N, Smith DJ. Changes in prescribing for bipolar disorder between 2009 and 2016: national-level data linkage study in Scotland. Br J Psychiatry 2019; 215: 415–21. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 30.

Kessing LV. Why is lithium [not] the drug of choice for bipolar disorder? a controversy between science and clinical practice. Int J Bipolar Disord 2024; 12: 3. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 31.

Høiseth G, Bentsen H. Bruk av antipsykotiske depotinjeksjoner. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2012; 132: 301–3. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 32.

Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. LOV-2017-02-10-06. Lov om endringer i psykisk helsevernloven mv. (økt selvbestemmelse og rettssikkerhet). https://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/lov/2017-02-10-6 Accessed 14.3.2023.

- 33.

Helsedirektoratet. Samdata spesialisthelsetjenesten. Tvungent psykisk helsevern uten døgnopphold. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/statistikk/samdata-spesialisthelsetjenesten/tvungent-psykisk-helsevern-uten-dognopphold Accessed 28.12.2023.

- 34.

Helsedireketoratet. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for legemiddelbehandling ved psykoselidelser. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/psykoselidelser-legemiddelbehandling Accessed 16.1.2025.

- 35.

Medicinrådet. Medicinrådets behandlingsvejledning vedrørende antipsykotika til behandling af psykotiske tilstande hos voksne. https://medicinraadet.dk/anbefalinger-og-vejledninger/behandlingsvejledninger-og-laegemiddelrekommandationer/antipsykotika-til-voksne Accessed 3.11.2023.

- 36.

Berentzen L-C. Medisinrapport fra tidlig psykosebehandling. https://www.oslo-universitetssykehus.no/avdelinger/klinikk-psykisk-helse-og-avhengighet/forsknings-og-innovasjonsavdelingen-i-pha/regionalt-kompetansesenter-for-tidlig-intervensjon-ved-psykoser/medisinrapport-fra-tidlig-psykosebehandling Accessed 20.1.2024.

- 37.

Gjerden P, Bramness JG, Tvete IF et al. The antipsychotic agent quetiapine is increasingly not used as such: dispensed prescriptions in Norway 2004-2015. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2017; 73: 1173–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 38.

Debernard KAB, Frost J, Roland PH. Kvetiapin er ikke en sovemedisin. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2019; 139. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.19.0205. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 39.

Tran LH. Forgiftninger med kvetiapin. Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo, 2021. https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/87026 Accessed 2.4.2025.

- 40.

Haug JB, Myhr R, Reikvam A. Pharmacy sales data versus ward stock accounting for the surveillance of broad-spectrum antibiotic use in hospitals. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011; 11: 166. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 41.

PROTECT Work Package 2. Inpatient drug utilization in Europe: nationwide data sources and a review of publications on a selected group of medicines (PROTECT project). Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2015; 116: 201–11. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 42.

WHO. ATC/DDD Toolkit. https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/indicators Accessed 17.8.2024.

- 43.

Skaare D, Hannisdal A, Kalager M et al. Måling av bruk av bredspektrede antibiotika i sykehus med etablerte og nye indikatorer. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2023; 143. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.22.0427. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 44.

Bale M, Holsen M, Osvoll KI et al. Helseatlas for psykisk helsevern og rusbehandling. https://apps.skde.no/helseatlas/files/psykiskhelsevernogrus.pdf Accessed 19.4.2023.