A woman in her mid-thirties was admitted to hospital due to confusion, apathy, weight loss and sleep disturbance. This article describes various ethical dilemmas involved in diagnosis and treatment.

A previously healthy woman in her mid-thirties consulted a doctor due to confusion, apathy, sleep disturbance and involuntary weight loss over the preceding month. Treatment with oral escitalopram 10 mg daily was initiated on suspicion of depression. Two weeks later, the woman was admitted to the emergency department. Upon admission, she spoke with considerable latency and had difficulty expressing herself. Her general condition was good and vital signs were normal. Findings from physical examination and preliminary blood tests were normal. There was no evidence of focal neurological deficits.

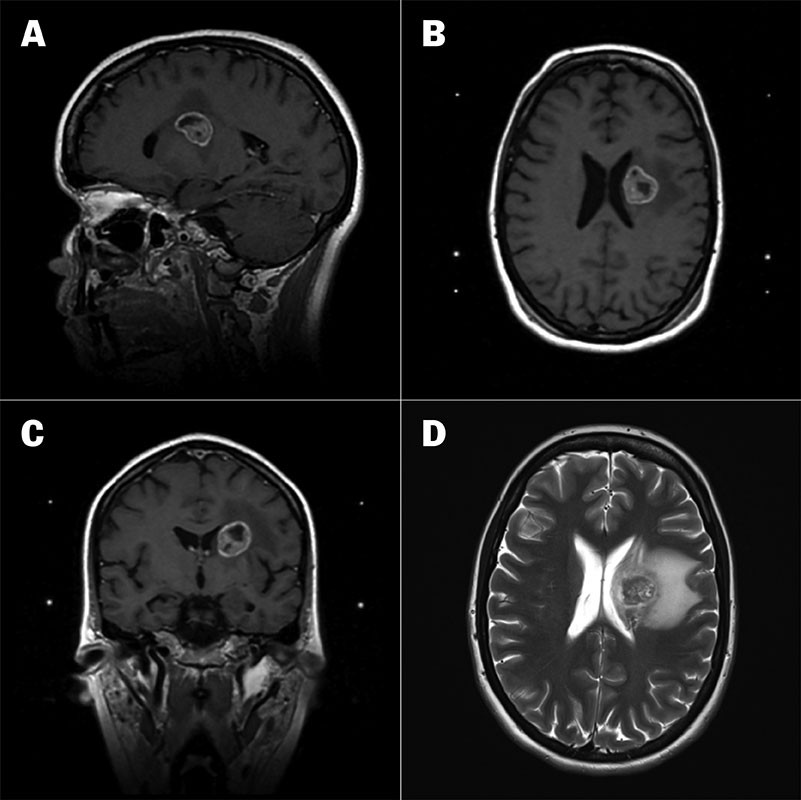

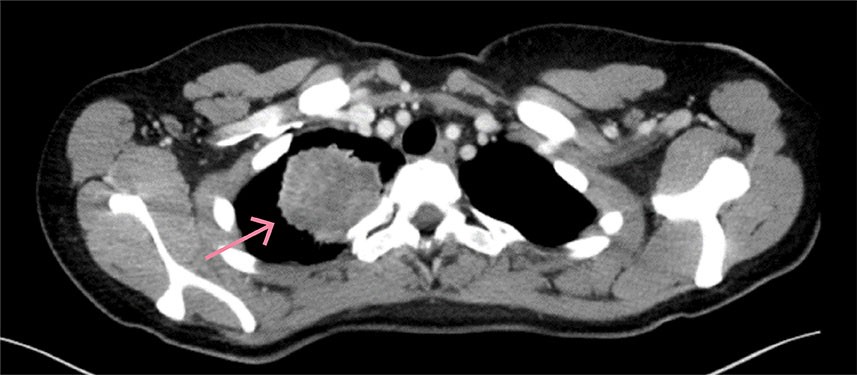

Brain CT and MRI revealed a 23 mm large expansive process and perifocal oedema in the left thalamus, exerting a mass effect on the adjacent left lateral ventricle (Figures 1a–d). A chest CT revealed a 5.6 cm tumour in the right upper lobe (Figure 2). Enlarged mediastinal paratracheal lymph nodes were observed on the right side (station 4R) in addition to enlarged paraaortic lymph nodes (station 6R).

Lung cancer with metastasis to the lymph nodes and brain was now suspected. Fine-needle aspiration cytology after bronchoscopic biopsy of lymph node 4R showed metastasis from poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma, confirming the diagnosis.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths in Norway (1). Most patients are still diagnosed at a stage of the disease where curative treatment is not an option. However, modern treatments such as immune checkpoint inhibitors can lead to long-term stable disease in some advanced-stage patients (2). Brain metastases can be treated with surgery, stereotactic radiotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy. Systemic therapy with regular MRI check-ups can be sufficient for patients with asymptomatic metastases (3, 4). Our intention was to admit the patient for stereotactic gamma knife radiosurgery of the brain metastasis and a new bronchoscopic biopsy, as the initial examination provided insufficient material for further investigation.

Anti-oedema therapy with oral dexamethasone 4 mg x 4 was initiated with a tapered dosage. The patient was on maternity leave and living with her parents, who were now taking care of her child, when her mother called the hospital to report that the patient was increasingly apathetic, had difficulty expressing herself and did not want to return to the hospital to undergo gamma knife radiosurgery and a new biopsy. Following a discussion among the doctors and nurses in the Department of Pulmonary Medicine who had attended to the patient, it was determined that she did not have the capacity to consent. This was based on her reduced ability to express a conscious choice, difficulty understanding relevant information and the likely consequences of not consenting to diagnosis and treatment. A formal decision was made under chapter 4A (5) of the Patient and User Rights Act (Norway), and it was decided to transport the patient by ambulance, by force if necessary, to carry out further diagnostics and cancer treatment.

When the ambulance personnel arrived, the patient did not want to go with them, but she reluctantly entered the ambulance without the need for coercion. The following day, the patient underwent gamma knife radiosurgery and was cooperative throughout the process. Further bronchoscope-guided fine-needle aspiration of lymph node 4R was carried out under anaesthesia. Cytology showed non-small cell carcinoma with no clear adeno or squamous differentiation, consistent with non-small cell carcinoma NOS (not otherwise specified). Immunohistochemical testing for ALK and ROS1 was negative, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) identified no actionable mutations for targeted treatment. PDL1 expression was estimated at < 75 %. Blood tests for paraneoplastic syndromes were negative.

During her hospital stay, the patient exhibited fluent and non-fluent aphasia, apraxia and possible confusion with some anxiety. Her substantially reduced food and fluid intake had led to rapid weight loss, necessitating supplemental parenteral nutrition and fluids. An interdisciplinary assessment by a psychiatrist, neurologist, neurosurgeon and pulmonologist concluded that the patient did not have the capacity to consent. Every effort was made to provide voluntary health care, but coercion was also used. For example, ward nurses physically restrained her when she tried to leave the ward. They also sedated her with intravenous or subcutaneous midazolam, administered parenteral nutrition and carried out personal hygiene care without her consent. One nurse wrote a report of concern about the insufficient justification for the formal decision to use coercion because several of the staff were unsure of how much coercion could be exercised, and what constituted an infringement of the patient's rights. The County Governor was consulted, and a more comprehensive formal decision to use coercion was drawn up, giving more detailed descriptions of which interventions were absolutely vital for the patient's medical care. The social worker played a key role in the treatment team and helped the patient's parents to apply for financial support from NAV and temporary guardianship.

The case and the forced treatment were discussed with representatives from the Clinical Ethics Committee and the pulmonology group. Whether to administer immune checkpoint inhibitors as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy was specifically discussed. We chose to administer the maximum possible treatment, even if this meant more adverse effects for the patient. Five weeks after her admission date, the patient started systemic therapy consisting of intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg, pemetrexed 750 mg and carboplatin 630 mg, administered every three weeks for four cycles. Dexamethasone was continued for oedema around the brain metastasis.

In our experience, the use of coercion in cancer treatment is extremely rare. It was very intrusive and hard for the patient and challenging for the healthcare personnel involved. It later emerged that the patient had found the first bronchoscopy very unpleasant. She was also worried about the gamma knife radiosurgery, which had been explained to her as a 'radiation knife to the head', a concept that was difficult to grasp in terms of scope. She later explained that this was why she was reluctant to return to the hospital. However, this was not picked up by the healthcare personnel who made the formal decision to use coercion at the time. Her aphasia made it very difficult to assess whether she had understood that the second bronchoscopy would be performed under anaesthesia to avoid discomfort.

The patient's condition in hospital gradually deteriorated, with alternating apathy and agitation, aphasia and undernutrition. Challenging situations arose in the ward, with nurses having to restrain the patient to prevent her leaving. The staff considered this highly stressful, particularly because they were uncertain what the patient understood and was able to communicate.

The anatomical location of the brain metastasis corresponded with the symptoms. Nevertheless, there was discussion of whether the patient could also have severe depression, anxiety and/or be experiencing a crisis reaction, and if so, which medications might help. During repeated psychiatric observations, the primary aetiology of her condition was identified as organic brain changes. Antipsychotics were advised against in favour of treatment with benzodiazepines in the form of oral diazepam 5 mg up to x 4, subcutaneous/intravenous midazolam 1–2 mg and the continuation of oral escitalopram 10 mg daily.

Three weeks after the date of admission, an EEG showed no definite abnormality. A brain MRI taken four weeks after the gamma knife radiosurgery showed persistent perifocal oedema around the largest metastasis. After thorough discussion with an oncologist and neurosurgeon, the decision was made to administer intravenous bevacizumab 400 mg every fourteen days, for a total of four courses, as anti-oedema therapy.

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inhibits tumour vascularisation. Several countries, including the United States, use bevacizumab to treat tumours and radiation-induced brain oedema, but this application is controversial (6). The antibody is used as a second-line treatment in cases of insufficient efficacy of dexamethasone in the treatment of oedema or in patients who suffer unsustainable adverse effects. In such cases, the aim is to try to reduce symptoms associated with radiation necrosis and tumour-associated oedema (7). In Norway, bevacizumab does not have an approved indication for reducing oedema. Oncologists with experience of using this drug were therefore consulted before the treatment was initiated.

Two months after her initial admission to hospital, the patient was transferred to a rehabilitation facility, also under a decision to use coercion. Two weeks later, her condition worsened, and she exhibited increasing agitation and distress. She had visual and auditory hallucinations and was assessed as having an elevated risk of suicide. She was therefore moved to the psychiatric ward for compulsory observation in accordance with chapter 3 (8) of Norway's Mental Health Care Act. The patient subsequently denied having suicidal ideation, and no psychotic symptoms, challenging behaviour or delusions were observed. She expressed a desire to continue her cancer treatment and had hopes of eventually returning home. After six days, a decision was made to end the compulsory observation in the psychiatric ward as there was no evidence that the patient had a severe mental disorder. However, her apathy, aphasia and disorientation were considered too severe for her to return to the rehabilitation centre. She was transferred back to the Department of Pulmonary Medicine. Two weeks later, another attempt at rehabilitation was made. After three weeks in rehabilitation, she was transferred to primary care as her functional status remained unstable and insufficient for her to live at home. She still spoke with considerable latency but was communicating more with the staff. With no other primary care options available, she was moved to a nursing home in her home municipality. Two months later, she was offered sheltered housing beside elderly patients, but neither the patient nor her family wanted this. Instead, the patient moved in with her parents and child after a total of six months in the institution. The decision on coercive treatment expired one month later.

It was difficult to know where to place the patient for her to receive the best possible medical care throughout the process. The Department of Pulmonary Medicine at Haukeland University Hospital has limited experience with forced treatment, but her primary diagnosis of lung cancer made it challenging to find another suitable place. The primary care service lacked the resources to provide rehabilitation for a young patient with such a complex symptom profile, and at one point, she was also deemed too impaired for rehabilitation in the specialist health service. The uncertainty and discussions about where the patient would receive the best possible care caused considerable stress for the patient and her family. Dealing with prognostic uncertainty in terms of planning and optimising the patient's care pathway was also a challenge. Would she live a long life, or should plans be made for terminal illness and the future care of her child?

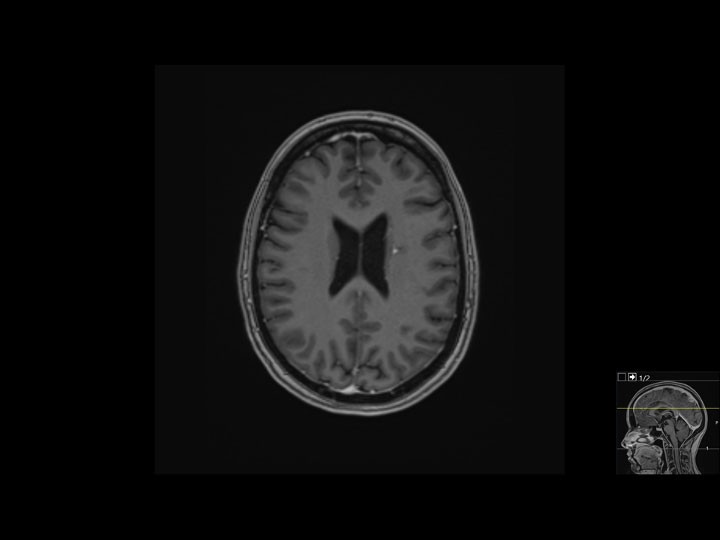

After discharge, the patient's mental health recovered and she returned to her normal weight. Following initial systemic therapy, which also included carboplatin and bevacizumab, she received intravenous pembrolizumab and pemetrexed every three weeks for a total of two years. She initially remembered little of what she had gone through, but subsequently expressed a need to process and understand her experience, and her memories have gradually resurfaced in 'flashbacks'. The topic of prognosis has been raised in several consultations, with the patient asking if she is healthy now. We informed her that the absence of signs of relapse four years after symptom onset and two years after her treatment was paused gives hope for a long-term positive outcome. Imaging shows only minor residual changes (Figure 3). The patient now lives in her own flat with her child and is looking for work. Here functional status is 0 (normal functioning).

Discussion

Determining whether to administer cancer treatment without the patient's consent presents several ethical and legal dilemmas, particularly if there is disagreement between the patient's family and healthcare personnel about what is best for the patient (9). In this case report, the family agreed that cancer treatment was the right course of action, not least due to the patient's young age. When her condition improved, the patient herself confirmed that she wanted treatment.

How far healthcare personnel should go to administer coercive cancer treatment is open to discussion, particularly since the treatment can lead to potentially life-threatening and distressing adverse effects. The criteria for administering forced medical care require that withholding medical care would cause substantial harm to health, the care is deemed necessary and the intervention is proportionate to the need for care, see section 4A-3 of Norway's Patient and User Rights Act (5). The clinicians and the patient's family concurred that these criteria had been met, as the patient would die within a short period of time without treatment for the brain metastasis and undernutrition.

Chapter 4A of the Patient and User Rights Act only applies to patients who do not have the capacity to consent. In this case, the patient's fluent and non-fluent aphasia made it difficult to assess her capacity to consent. Ensuring autonomous choice and informed consent can be difficult in patients with a life-threatening illness, even in patients with the capacity to consent (10). The law also requires that efforts are made to build trust in order to facilitate medical care without the use of coercion. Whether sufficient efforts were made with our patient is open to discussion. Could we, for example, have explained the 'radiation knife' in a way that would have made her less anxious, and reassured her more about the new bronchoscopy being performed under general anaesthesia? Assessing capacity to consent based on information provided by the patient's family was also problematic, even for healthcare personnel who had recently examined the patient. This case report illustrates the importance of trying to strengthen the patient's capacity for autonomy and opportunity for shared decision-making, even in very challenging situations (11).

An important lesson from this case report is that external expertise should be sought to assist in difficult situations. It would have been better to contact the County Governor when the decision to use coercion was made, as shortcomings in the initial decision left the nurses uncertain about how to proceed. It can also be useful to contact the Clinical Ethics Committee for advice. This matter was discussed in the monthly meeting of the doctors in the Department of Pulmonary Medicine, representatives from the Clinical Ethics Committee and the Chaplaincy and Ethics Section. The nurses and doctors both experienced moral distress, which occurs when clinicians are faced with ethical challenges and feel responsible for addressing them but feel unable to take the ethically appropriate action due to various constraints. (12). Nurses' professional ethics standard, which in terms of lung patients primarily entails care in line with the patient's wishes and autonomy, was challenged. This led to feelings of inadequacy and a sense of falling short of the threshold for good patient care on a pulmonary ward.

Departmental management implemented various measures based on the feedback. Expertise was sought from units with experience in forced treatment to counsel and debrief the care team. This helped the staff to cope with the situation. The social worker also experienced moral distress, as navigating the patient's rights in the primary care service was challenging due to resource constraints and differing understandings of the patient's gradual recovery of her capacity to consent and full capacity to care for her child. In retrospect, we can see that more meetings between different treatment providers would likely have helped alleviate the stress for the patient, her family and the healthcare personnel.

The patient's mental health status was complex, and we believe the onset of cognitive symptoms was due to the brain metastasis. As she had an organic brain disease, she did not fall under the 'somatic health care for patients with mental disorders' category, which can also pose legal and ethical challenges (13). The patient has been clear that she never felt depressed, and she has subsequently expressed that the use of coercion was unnecessary, although she is grateful for the medical care she received. She has had to spend considerable time and effort processing her experience of forced treatment, in addition to dealing with the diagnosis itself. Losing control of her daily life and feeling misunderstood were frightening and dramatic experiences for her. The isolation was compounded by the visitor restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic and the assessment that she was too ill to see her child in the initial stages. This case report also illustrates challenges often encountered in relation to which ward the patient should primarily be assigned to, as the patient had neuropsychiatric symptoms from a pulmonary condition for which she underwent gamma knife radiosurgery and systemic cancer therapy. We call for the health service to be more tailored towards providing comprehensive care pathways for patients with complex needs, including more rehabilitation options within the hospital setting.

Balancing ethical principles of respecting autonomy, doing good and doing no harm can be particularly challenging for medical care characterised by a large degree of medical and existential uncertainty (14, 15). In the past, the prognosis for advanced lung cancer was very poor, but modern treatments now mean that a considerable subgroup of patients can have many good years of life with stable disease (2). Nevertheless, the diagnosis entails challenges in relation to hope and uncertainty for patients, their families and healthcare personnel (16). This uncertainty can also pose difficulties for external agencies, as seen in the assessments of our patient's ability to care for her child and suitable living arrangements in her home municipality. In hindsight, it might have been better for the patient, her family and municipal agencies if the specialist health service had placed a clearer emphasis on the possibility of a long-term treatment response despite the life-threatening nature of the illness. Everyone involved is glad that the patient responded so well to treatment. However, she has to live with the prognostic uncertainty that comes with a condition that is, in principle, incurable.

Patient's perspective

'I didn't have a job and was looking after my child on my own. A lot of people assume that you must be depressed. I think the decision to use coercion was unnecessary; obviously I wanted to get well and live. I dreaded the bronchoscopy, had little appetite and didn't feel much like talking. I had to process the shocking news. Being forced to have treatment was degrading, and the COVID restrictions and being under a coercion order for a lengthy period of time was stressful, because I wanted to go home to my child.'

Conclusion

This case report illustrates ethical dilemmas in the use of coercion during cancer treatment, both for patients and healthcare personnel. Follow-up debriefing sessions should be held with staff. A shared understanding of the intent and scope of the forced treatment should be established at the earliest stage possible. Detailed interdisciplinary discussions, external expertise and an ongoing dialogue with the patient and their family are important for safeguarding the patient's capacity for autonomy to the greatest extent possible.

The patient has consented to publication of this article, and has provided valuable input to the manuscript. The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Kreftregisteret. Lungekreft. https://www.kreftregisteret.no/Temasider/kreftformer/Lungekreft/ Accessed 24.4.2024.

- 2.

Garassino MC, Gadgeel S, Speranza G et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J Clin Oncol 2023; 41: 1992–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonalt handlingsprogram for lungekreft, mesoteliom og thymom. http://nlcg.no/wp-content/uploads/211223-Nasjonalt-handlingsprogram-for-lungekreft-mesoteliom-og-thymom-23.12.21.pdf Accessed 24.4.2024.

- 4.

Vogelbaum MA, Brown PD, Messersmith H et al. Treatment for Brain Metastases: ASCO-SNO-ASTRO Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40: 492–516. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Helsedirektoratet. Pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven med kommentarer. https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/945/IS-%208%202015%20%20Rundskrivpasientogbrukerrettighetsloven.pdf Accessed 24.4.2024.

- 6.

Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonalt handlingsprogram for hjernesvulster. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/diffusehoygradige-gliomer-hos-voksne-handlingsprogram/behandling-av-recidiv/medikamentell-behandling Accessed 24.4.2024.

- 7.

Levin VA, Bidaut L, Hou P et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bevacizumab therapy for radiation necrosis of the central nervous system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 79: 1487–95. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Lovdata. Lov om etablering og gjennomføring av psykisk helsevern. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-62 Accessed 24.4.2024.

- 9.

Pope TM. Providing cancer treatment without patient consent. https://ascopost.com/issues/february-25-2018/providing-cancer-treatment-without-patient-consent/ Accessed 24.4.2024.

- 10.

Skaar E, Ranhoff AH, Nordrehaug JE et al. Conditions for autonomous choice: a qualitative study of older adults' experience of decision-making in TAVR. J Geriatr Cardiol 2017; 14: 42–8. [PubMed]

- 11.

Gulbrandsen P, Clayman ML, Beach MC et al. Shared decision-making as an existential journey: Aiming for restored autonomous capacity. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 99: 1505–10. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Rushton CH. Moral Resilience: A Capacity for Navigating Moral Distress in Critical Care. AACN Adv Crit Care 2016; 27: 111–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Bjorå IKH, Jorem J, Tveito M. Tvangsbehandling av somatisk sykdom ved psykisk lidelse. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2019; 139. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.18.0553. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Orstad S, Fløtten Ø, Madebo T et al. "The challenge is the complexity" - A qualitative study about decision-making in advanced lung cancer treatment. Lung Cancer 2023; 183. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2023.107312. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Schaufel MA, Nordrehaug JE, Malterud K. "So you think I'll survive?": a qualitative study about doctor-patient dialogues preceding high-risk cardiac surgery or intervention. Heart 2009; 95: 1245–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Brustugun OT. Håp når håpløsheten truer. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2023; 143. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.23.0095. [PubMed][CrossRef]