An immunosuppressed woman in her seventies was hospitalised following convulsions. After admission, she developed a fever and experienced confusion. The investigation revealed a rare condition.

The patient was a woman in her seventies who had grown up in Latin America and been living in Norway for several decades. Ten years before the event in question, she underwent a heart transplant due to Chagas cardiomyopathy and was immunosuppressed, with mycophenolate, cyclosporine and prednisolone. She had an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) due to arrhythmia.

The patient was admitted as an emergency to the Department of Medicine at her local hospital after being found unconscious by her son, who had spent half an hour trying to waken her up. She had bitten her tongue and urinary incontinence was observed, leading to suspicion of a convulsion. She had been experiencing headaches and visual disturbances for the past few weeks. Upon admission, she was alert and oriented, with a temperature of 37.8°C. Neurological examination findings were normal. Brain CT on the same day showed no relevant pathology. Due to a positive urine sample (haemoglobin (Hb) 4+, leukocytes 2+) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 72 mg/L (reference range < 5), intravenous cefotaxime 1 g × 3 was started the day after admission for a possible urinary tract infection. No bacterial growth was observed in urine or blood cultures. A neurologist was consulted, who recommended an outpatient neurological assessment after discharge.

On the fifth day after admission, the patient had a convulsion and was transferred to the Department of Neurology at a larger hospital. Upon arrival, she appeared confused and had inverted plantar reflexes. Brain CT with contrast showed normal findings. Antiepileptic treatment with levetiracetam tablets 250 mg × 2 was initiated. The next day, the patient had a high fever. Encephalitis was suspected and a lumbar puncture was performed, revealing an elevated cell count of 21 × 106 cells/L (< 5), of which 20 × 106 were mononuclear cells/L, and protein level of 0.41 g/L (0.15–0.40). The ratio between glucose in cerebrospinal fluid (3.6 mmol/L) and in serum (6.6 mmol/L) was 0.55 (> 0.6). Intravenous aciclovir 10 mg/kg × 3 was initiated on suspicion of viral encephalitis. EEG eight days after the initial admission showed non-specific changes, but no epileptiform activity. The patient was transferred back to the Department of Medicine at the local hospital.

The patient had convulsions, headache, fever and was confused. Clinical presentation and spinal fluid findings were most consistent with infectious encephalitis.

No bacterial growth was found in a cerebrospinal fluid culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a panel for infections in the central nervous system (FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis (FAME) panel) was negative for all agents, including herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. No antibodies for autoimmune encephalitis were found in cerebrospinal fluid or serum. Aciclovir was discontinued, and on the tenth day after the initial admission, the patient was transferred to the infectious disease high dependency unit at the regional hospital. Upon transferral, she was alert and oriented to place but not time.

The symptoms and cerebrospinal fluid findings were consistent with encephalitis, but no aetiological agent was identified. The differential diagnosis considered whether the symptom profile could be indicative of another unrecognised infection and delirium, and whether the elevated cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid could be due to a recent convulsion.

Brain MRI was desired as part of the investigation for encephalitis but was considered too risky due to the uninsulated ICD leads in the myocardium. Instead, a new brain CT with contrast was performed on day 11 after the initial admission, with no relevant findings. A CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis was performed at the same time, without any findings of a focus of infection. Daily blood cultures for the first three days after transfer showed no bacterial growth. PCR testing for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and JC polyomavirus in plasma was negative.

There was discussion of whether the symptoms could be related to Chagas disease. Reactivation of this disease with involvement of the central nervous system is rare but has been reported in immunosuppressed patients (1). Fever, headache, convulsions and focal neurological deficits are typical findings. Cerebrospinal fluid often shows moderate pleocytosis with a predominance of mononuclear cells, elevated protein levels and, in some cases, a reduced glucose ratio. Brain imaging can reveal pseudo-tumours (known as chagomas), which with contrast enhancement on CT appear as hypodense lesions, but cases with normal findings have also been described. Cerebrospinal fluid is examined through microscopy of a Giemsa-stained smear and with direct microscopy of untreated cerebrospinal fluid (wet mount), which can detect motile Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes. Wet mounts require rapid sample handling, as the parasites start to break down and lose motility after 15–20 minutes. PCR has a higher sensitivity than microscopy, but it is currently unavailable in Norway.

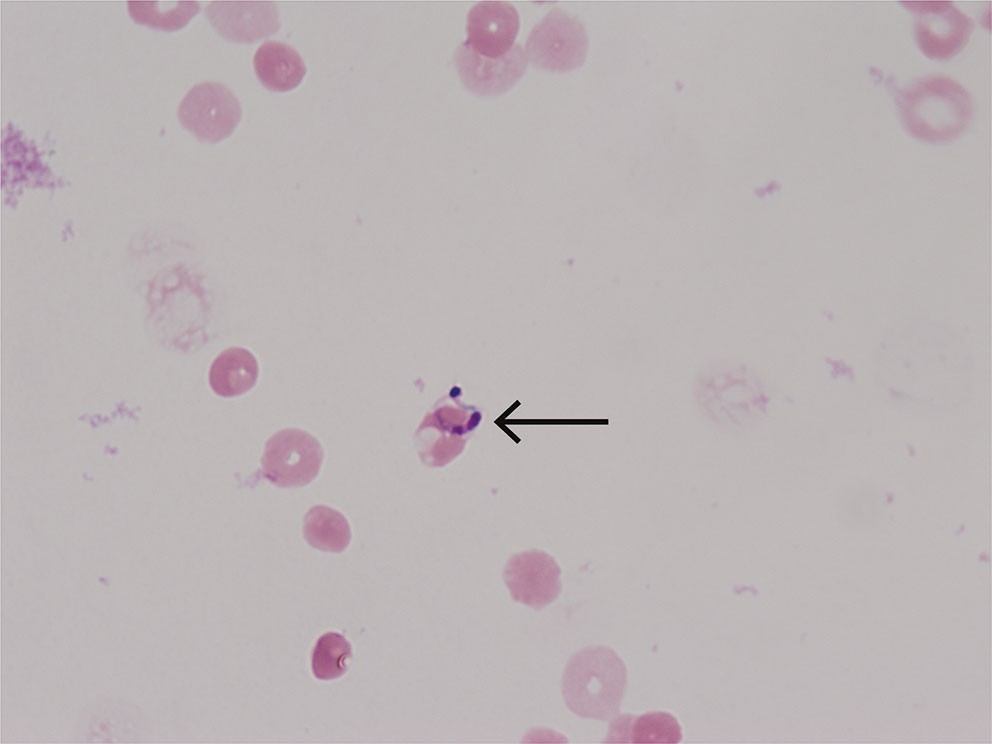

On suspicion of Chagas encephalitis, a new lumbar puncture was performed. Live Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes were found in the wet mount (direct microscopy of untreated cerebrospinal fluid) (see video at tidsskriftet.no) and multiple parasites in a Giemsa-stained smear (Figure 1). The diagnosis of Chagas encephalitis was thus made 12 days after the initial admission. Spinal fluid and EDTA blood samples were sent to the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, where PCR testing subsequently confirmed Trypanosoma cruzi DNA.

The mortality rate for Chagas encephalitis is high (1), but early antiparasitic treatment improves prognosis and survival. Benznidazole is the first-line treatment for both acute and chronic Chagas disease, normally in doses of 5–7.5 mg/kg per day for 60 days (2, 3). Nifurtimox is an alternative but can have more adverse effects. Both medications are given perorally but are not registered in Norway. Nor are they available in most European countries. Detection of parasites by microscopy confirmed the diagnosis and enabled us to order the medications from the World Health Organization (WHO), which distributes them on request.

Over the next few days, the patient deteriorated, experiencing pharyngeal paralysis, aphasia and somnolence. Three days after diagnosis and 15 days after the initial admission, the medications arrived, and treatment with benznidazole tablets 5 mg/kg was initiated. The patient deteriorated further over the next few days. She became unresponsive and scored 5–6 on the Glasgow Coma Scale, where < 9 is considered a severe impairment of consciousness.

EEG showed severe encephalopathy with epileptiform activity. Brain CT 17 days after the initial admission showed increased density in both frontal lobes with signs of bleeding, consistent with necrotic-haemorrhagic nodular lesions typical of Chagas encephalitis. The benznidazole dose was increased to 7.5 mg/kg, and nifurtimox tablets 10 mg/kg were given as an adjunctive treatment. In consultation with cardiologists at the transplant centre at the national hospital, Rikshospitalet, immunosuppression was changed from mycophenolate to azathioprine, as this reduces the risk of Chagas disease reactivation (4). The patient's troponin T level remained unchanged, ECG findings were normal, and no clinical or echocardiographic evidence of Chagas myocarditis reactivation was found.

One week after initiating treatment, the patient improved. She was alert, and could squeeze our hands and move her toes upon request. After discussion with colleagues abroad, nifurtimox was discontinued and benznidazole was reduced to 5 mg/kg to minimise the risk of adverse effects. The patient continued to improve gradually. She had difficulty swallowing with risk of aspiration and received nutrition via a PEG tube. After one month of treatment, she began to regain language function and responded appropriately with single words. She was mobilised and able to walk with support upon transfer to a rehabilitation facility 1.5 months after starting treatment.

After six weeks of multidisciplinary rehabilitation in the specialist health service, she was transferred to rehabilitation in the primary care service. At the hospital check-up one month after completing the 60-day course of benznidazole, the patient was using a walker and was alert and oriented. She was eating normally, and the PEG tube was removed. The cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid had normalised, and Trypanosoma cruzi PCR in blood and cerebrospinal fluid was negative. Encephalitis check-ups were completed, and the patient continued to be followed up by a cardiologist as before.

Discussion

Chagas disease is endemic in Latin America, where it is a common cause of cardiac death due to ventricular arrhythmias, heart failure and/or thromboembolic events (3, 5). The vector-borne disease is caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, which is most commonly transmitted by blood-sucking triatomine bugs (6). Transmission can also occur from mother to child, and via contaminated food, blood and organ transplantation.

The infection is typically asymptomatic to start with, but a few patients develop acute myocarditis or meningoencephalitis a few weeks after being infected. Patients' infections remain chronic, and 30–40 % develop clinical disease after 10–30 years, most commonly in the form of cardiomyopathy. Heart transplantation is a life-saving treatment for severe Chagas cardiomyopathy, but there is a high risk of parasite dissemination to the transplanted heart and reactivation of the disease when the patient is immunosuppressed (7).

Our patient was followed up as recommended after heart transplantation, with PCR monitoring of Trypanosoma cruzi. One year after the transplant, she had reactivation of Chagas myocarditis, with arrhythmias and positive PCR findings in myocardial biopsy and blood. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator was fitted, and she was treated with benznidazole for 90 days.

Chagas encephalitis is a rare but serious condition. Mortality in immunocompromised patients is reported to be 85 % (1, 8). However, our patient's history shows that even with a coma and severe neurological findings, treatment can lead to a life with normal cognitive function and no apparent sequelae.

Chronic Chagas disease is a common condition, with a risk of cardiomyopathy and gastrointestinal disease. The disease is endemic in Latin America but has spread to other continents through migration. The prevalence among Latin American immigrants to Europe is estimated at 4 % (9). The majority of people with asymptomatic chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection are likely undiagnosed, as healthcare personnel in non-endemic areas often have little knowledge of the disease.

Our patient had been admitted with arrhythmia and heart failure in Norway, but the diagnosis of Chagas cardiomyopathy was only made when she was subsequently hospitalised with ventricular tachycardia during a stay in Latin America. Heart transplantation is not an uncommon treatment for Chagas disease. In Brazil, Chagas cardiomyopathy is the third most common indication for heart transplantation (10). In a report from the United States, the risk of reactivation with myocarditis in the graft was as high as 61 % (7). This is the background for the recommendation of post-transplant follow-up with PCR testing from blood and the myocardium, and treatment upon reactivation, which our patient received with subsequent disease control for many years before experiencing encephalitis reactivation. Regular monitoring for reactivation is recommended during the first year after transplantation, one month after any steroid treatment for rejection, and if fever occurs or signs of myocarditis develop (11).

In chronic asymptomatic Trypanosoma cruzi infection, serology with antibody detection is the most sensitive diagnostic method. In acute infection or reactivation, the parasites can often be detected in blood or cerebrospinal fluid by microscopy or PCR. Microscopy of cerebrospinal fluid in suspected encephalitis is a relatively simple method that requires few resources, and in this case, it contributed to rapid clarification (video). Routine microscopy of a Gram stain from cerebrospinal fluid will not detect the infection, as special Giemsa staining is required to see the parasites (Figure 1). Bacterial culture and standard PCR with a central nervous system panel will be negative.

Benznidazole and nifurtimox have shown clinical efficacy against Trypanosoma cruzi in randomised controlled trials (2). Fexinidazole, which is used to treat African trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, has recently been shown to be effective against Chagas disease in a randomised controlled trial but is not currently in use due to adverse effects in the form of neutropenia (12). Benznidazole is the most extensively tested treatment and is particularly effective in acute and early chronic infection. Clinical efficacy trials are based on seroconversion or PCR negativity after treatment. The largest randomised controlled trial of benznidazole in patients with chronic Chagas disease and cardiomyopathy showed that significantly more patients were PCR-negative after treatment, but over five years of follow-up, no effect was observed on the risk of worsening cardiomyopathy (13).

Treatment of asymptomatic seropositive patients has not been studied in large-scale randomised controlled trials, but non-randomised controlled trials have shown a reduced risk of cardiomyopathy and reduced mortality (14, 15). Treatment of asymptomatic patients is therefore common practice in most countries (16). Treatment is recommended as early in the course of the disease as possible, while in older patients with chronic Chagas disease and organ involvement, the risk of adverse effects is weighed against the benefits (5). There are no clinical trials of encephalitis in immunosuppressed patients, but both benznidazole and nifurtimox have good penetration into the central nervous system, and we chose combination therapy for our patient when her condition became critical after starting benznidazole.

Chagas disease is normally a chronic condition for which treatment with medication is not urgent. However, in cases of acute infection or reactivation, prompt treatment is important.

Contact details for ordering benznidazole and nifurtimox and for advice on Chagas disease can be found at the WHO's website (17).

In Europe, Chagas disease is not vector-borne, but it can be transmitted from mother to child, or via blood or organ transplantation. In Norway, control measures have been introduced to prevent transmission during blood transfusion (18). Vertical transmission from seropositive mothers occurs in around 5 % of births and in up to 30 % if the mother is PCR-positive (3). More than 90 % of infants born with the infection are cured if treated in the first year of life (2). Benznidazole and nifurtimox are contraindicated during pregnancy, but treating fertile women can prevent transmission in subsequent pregnancies (19).

The Trypanosoma cruzi antibody test is performed at the National Reference Function for Serological Parasite Diagnostics at the University Hospital of Northern Norway. All patients of Latin American origin with arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, or enlarged viscera should be tested for Chagas disease. Screening and treatment of Chagas disease in asymptomatic Latin American immigrants in Europe are cost-effective (16). Antibody testing in risk groups and treatment of seropositives should also be recommended in Norway to prevent transmission during pregnancy and prevent organ complications of Chagas disease.

The patient has consented to publication of this article.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Pittella JE. Central nervous system involvement in Chagas disease: a hundred-year-old history. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2009; 103: 973–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

Santana Nogueira S, Cardoso Santos E, Oliveira Silva R et al. Monotherapy and combination chemotherapy for Chagas disease treatment: a systematic review of clinical efficacy and safety based on randomized controlled trials. Parasitology 2022; 149: 1679–94. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Pérez-Molina JA, Molina I. Chagas disease. Lancet 2018; 391: 82–94. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Bacal F, Silva CP, Bocchi EA et al. Mychophenolate mofetil increased chagas disease reactivation in heart transplanted patients: comparison between two different protocols. Am J Transplant 2005; 5: 2017–21. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Stroke Council. Chagas Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Current Clinical Knowledge and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 138: e169–209. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

Hasle G. Chagasteger. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2010; 130: 409. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Gray EB, La Hoz RM, Green JS et al. Reactivation of Chagas disease among heart transplant recipients in the United States, 2012-2016. Transpl Infect Dis 2018; 20. doi: 10.1111/tid.12996. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Ferreira MS, Nishioka SA, Silvestre MT et al. Reactivation of Chagas' disease in patients with AIDS: report of three new cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 25: 1397–400. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Requena-Méndez A, Aldasoro E, de Lazzari E et al. Prevalence of Chagas disease in Latin-American migrants living in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015; 9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003540. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Andrade JP, Marin Neto JA, Paola AA et al. I Latin American Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas' heart disease: executive summary. Arq Bras Cardiol 2011; 96: 434–42. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Campos SV, Strabelli TM, Amato Neto V et al. Risk factors for Chagas' disease reactivation after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2008; 27: 597–602. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Torrico F, Gascón J, Ortiz L et al. A Phase 2, Randomized, Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled, Proof-of-Concept Trial of Oral Fexinidazole in Adults With Chronic Indeterminate Chagas Disease. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76: e1186–94. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

BENEFIT Investigators. Randomized Trial of Benznidazole for Chronic Chagas' Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1295–306. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B et al. Long-term cardiac outcomes of treating chronic Chagas disease with benznidazole versus no treatment: a nonrandomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 724–34. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Viotti R, Vigliano C, Alvarez MG et al. Impact of aetiological treatment on conventional and multiplex serology in chronic Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011; 5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001314. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Requena-Méndez A, Bussion S, Aldasoro E et al. Cost-effectiveness of Chagas disease screening in Latin American migrants at primary health-care centres in Europe: a Markov model analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017; 5: e439–47. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 17.

World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). https://www.who.int/health-topics/chagas-disease/ Accessed 23.6.2023.

- 18.

Helsedirektoratet. Veileder for transfusjonstjenesten i Norge utgave 7.3 2017. https://helsedirektoratet.no/retninglinjer/veileder-for-transfusjonstjenesten-i-norge/ Accessed 23.6.2023.

- 19.

Álvarez MG, Vigliano C, Lococo B et al. Prevention of congenital Chagas disease by Benznidazole treatment in reproductive-age women. An observational study. Acta Trop 2017; 174: 149–52. [PubMed][CrossRef]