Main findings

One-third of patients in the study had raised the subject of diet with their general practitioner (GP), while half wanted advice and guidance on the association between diet and health.

The wish for dietary guidance was strongest among younger patients, men, patients with lower levels of education, patients who wanted to lose weight and patients taking medication for chronic conditions.

Diet is an important factor for health (1–5), and conditions resulting from diet-related risk factors are estimated to cause approximately 11 million deaths and 255 million years of life lost globally (6). Obesity is a growing public health problem, and the World Health Organization estimated that the prevalence of obesity tripled in the period 1975–2016 (7). Meta-analyses consistently show how diet is strongly associated with the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and a range of other conditions (1, 3, 5, 8). Assistance with lifestyle changes should be the primary approach for certain high-prevalence risk conditions (9). The effect of lifestyle interventions, such as dietary changes, on type 2 diabetes can often be significant, and in some cases surpass what can be expected from medication alone (10, 11).

One of the goals of Norway's Coordination Reform in the healthcare sector was for GPs to play a more active role in the prevention of lifestyle diseases (12). A qualitative study showed that patients with weight problems wanted their GP to raise the subject of weight and initiate a discussion about this even in consultations for other issues (13). Evidence shows that GPs are often hesitant to address weight out of fear of offending patients (14), and this tendency appears to become more pronounced as the severity of the weight problem increases (15).

Few studies address the extent to which diet is discussed with GPs in Norway and which patients have a desire for this. The aim of the study was to survey which patient groups had raised the subject of diet with their GP, who wanted guidance on how diet affects health, and whether there is correspondence between these patient groups.

Material and method

The cross-sectional survey is based on an anonymous survey conducted at 69 GP practices in Western Norway in 2022. The data were collected by 6th year medical students at the University of Bergen during their clinical placement in general practice (16). Each student distributed patient information and a questionnaire in the waiting room of a GP practice to 20 consecutive patients over the age of 18. The questionnaire was in Norwegian, but an English translation was also available. The patients completed the questionnaire themselves and returned it to the student in the envelope provided without any identifying markers.

Nine questions about dietary knowledge and the desire to receive dietary guidance and lose weight (questions 11–18) as well as questions about medication use (question 19) were included in the study. For the complete questionnaire, see Appendix 1 (in Norwegian) (questions 1–10 about food and finances were not part of the study). We also included sociodemographic variables, such as age, gender, whether the patient had children of their own, whether there were children living in the household, country of birth and highest level of completed education.

Before analysis, several of the variables were dichotomised. For questions regarding how often the patient had raised the subject of diet and how often they wanted this to be discussed, the response alternatives 'sometimes' and 'often' were conflated into 'yes', and 'never' was registered as 'no' (questions 11–12). Those who answered 'not relevant' were excluded from the calculations. The response alternatives 'to some extent' and 'to a large extent' were conflated into 'yes', while 'to a small extent' was registered as 'no' (questions 13–18). For medication use (question 19), the response was registered as 'no' for missing answers, while those who answered 'don't know' were excluded from the analysis. Medication use for chronic conditions was classified as 'yes' if the participant used medications in at least one of the following categories: cholesterol-lowering, blood pressure-lowering, other medications for heart disease, or medications for diabetes/blood glucose/obesity. If the question about children in the household was unanswered, the response was registered as 'no' if they also answered 'no' to the question on having children of their own. Responses with missing answers to the relevant variable were excluded from percentage calculations in descriptive analyses. In the regression analyses, only those who had responded to all the relevant variables for the analysis were included.

We used logistic regression to examine the likelihood of a patient wanting advice/guidance on the impact of diet on health (question 16) and whether the patient had raised the subject of diet (question 11). Unadjusted and adjusted results were presented as odds ratios with 95 % confidence intervals. Explanatory variables included sociodemographic variables, desire to lose weight and medication use for chronic conditions. Stata SE 17.0 was used to analyse the data.

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics Western Norway determined that the project did not require to be submitted for approval (application number 386617). The data collection was considered to be anonymous, and the patients were not compensated for participation or asked about their reason for contact with their GP.

Results

A total of 129 of the 166 medical students in general practice in Western Norway in 2022 contributed to the data collection. In total, 2571 patients were invited to participate. Forty of these were under the age of 18 and were excluded. Of the 2531 patients ≥ 18 years old, 2105 completed the questionnaire (83 % response rate). Among these, 30 did not answer questions 11–18 and were therefore excluded. Consequently, 2075 patients were included in the analyses. Of these, 1080 (52 %) were ≥ 50 years old and 1263 (63 %) were women (Table 1).

Table 1

Self-reported demographic data for patients in the waiting rooms of GP practices in Western Norway who completed a questionnaire on medication use for chronic conditions, dietary knowledge and a desire to receive dietary guidance and lose weight (N = 2075).

| Age (n = 2 063) | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 18–29 years | 291 (14) | |

| 30–39 years | 378 (18) | |

| 40–49 years | 314 (15) | |

| 50–59 years | 307 (15) | |

| 60–69 years | 328 (16) | |

| 70+ years | 445 (22) | |

| Sex (n = 2015) | ||

| Female | 1 263 (63) | |

| Male | 752 (37) | |

| Has children of their own (n = 2 000) | 1 516 (76) | |

| Has children living in the household (n = 1 671) | 590 (35) | |

| Place of birth (n = 2 031) | ||

| Norway | 1 790 (88) | |

| Asia. Africa. Latin America | 94 (4,6) | |

| North America. Oceania | 11 (0,5) | |

| Nordic region | 26 (1,3) | |

| West Europe | 35 (1,7) | |

| East Europe | 75 (3,7) | |

| Highest completed education (n = 2 019) | ||

| Primary/lower secondary school | 177 (9) | |

| Upper secondary school or vocational school | 963 (48) | |

| University/university college | 879 (44) | |

| Medication use | ||

| To reduce cholesterol (n = 2 038) | 478 (23) | |

| To reduce blood pressure (n = 2 054) | 588 (29) | |

| Other medications for heart disease (n = 2 043) | 273 (13) | |

| For diabetes/blood glucose/obesity (n = 2 046) | 224 (11) | |

| Other medications (n = 2 033) | 1 002 (49) | |

A total of 626 (33 %) of the patients had raised the subject of diet with their GP, 1023 (57 %) wanted the GP to raise the subject of diet, 1125 (56 %) wanted advice or guidance on how diet affects health, and 1243 (62 %) wanted to lose weight (Table 2). The vast majority (96 %) reported having the dietary knowledge they needed 'to a large extent' or 'to some extent'. However, 799 (40 %) reported confusion related to diet and dietary advice (Table 2).

Table 2

Self-reported dietary knowledge and desire to receive dietary guidance and lose weight among patients in the waiting rooms of GP practices in Western Norway (N = 2075).

| Question (number) | Questions and response alternatives (number answered = n) | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | In GP consultations, how often have you raised the subject of diet? (n = 1 905) | ||

| Never | 1 279 (67) | ||

| Sometimes | 599 (31) | ||

| Frequently | 27 (1) | ||

| 12 | In GP consultations, how often do you wish that the subject of diet was raised? | ||

| Never | 782 (43) | ||

| Sometimes | 912 (51) | ||

| Frequently | 111 (6) | ||

| 13 | I have the knowledge I need about diet (n = 2 040) | ||

| To a large extent | 1 195 (59) | ||

| To some extent | 761 (37) | ||

| To a small extent | 84 (4) | ||

| 14 | I would like my GP to talk to me about diet (n = 2 015) | ||

| To a large extent | 144 (7) | ||

| To some extent | 781 (39) | ||

| To a small extent | 1 090 (54) | ||

| 15 | I would like to change my diet (n = 2 005) | ||

| To a large extent | 259 (13) | ||

| To some extent | 998 (50) | ||

| To a small extent | 748 (37) | ||

| 16 | I would like advice/guidance on how diet impacts on my health (n = 2 013) | ||

| To a large extent | 301 (15) | ||

| To some extent | 824 (41) | ||

| To a small extent | 888 (44) | ||

| 17 | Diet and dietary advice confuse me (n = 2 008) | ||

| To a large extent | 168 (8) | ||

| To some extent | 631 (31) | ||

| To a small extent | 1 209 (60) | ||

| 18 | I would like to lose weight (n = 2 016) | ||

| To a large extent | 510 (25) | ||

| To some extent | 733 (36) | ||

| To a small extent | 773 (38) | ||

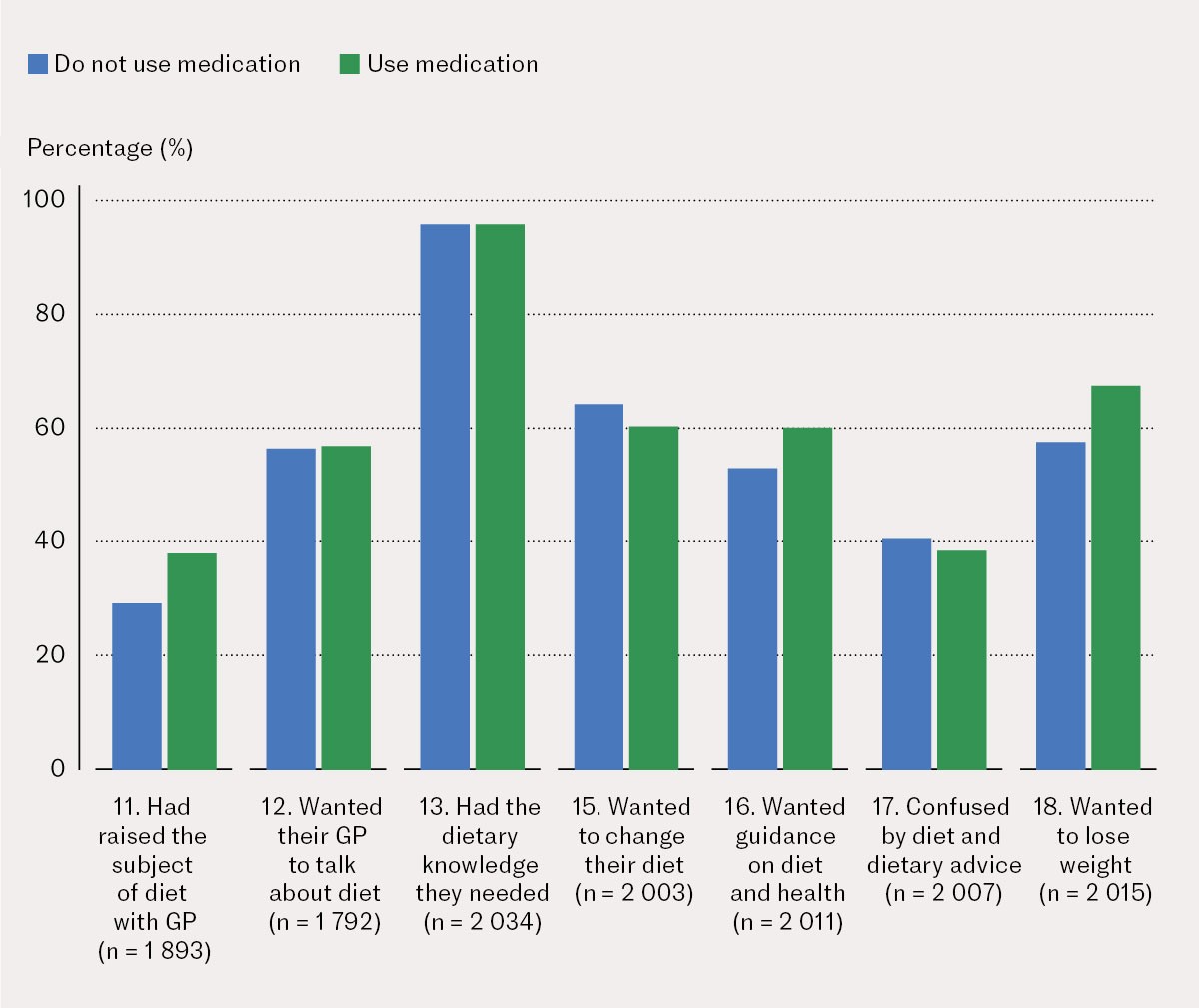

A total of 845 (41 %) patients used medication for a chronic condition. Of these, 295 (38 %) reported raising the subject of diet, compared to 328 (29 %) who did not use such medication. Of those who used medication for a chronic condition, 486 (60 %) indicated a desire to receive advice/guidance on how diet impacts on their health, compared to 637 (53 %) who did not use such medication (Figure 1).

Logistic regression analysis for the desire to receive advice/guidance on how diet affects health showed that younger patients, men and patients with a lower level of education were more likely to want advice/guidance (Table 3). There was no difference in the desire to receive dietary guidance between patients born in Norway and others, or between patients with and without children of their own. Those who wanted to lose weight and those using medication for a chronic condition were more likely to want dietary guidance. The highest probability of wanting dietary guidance was found among patients who wanted to lose weight (odds ratio 2.62; 95 % confidence interval 2.14 to 3.20).

Table 3

Probability (odds ratio and 95 % confidence interval (CI)) of wanting advice/guidance about how diet affects health, and proportion (%) of respondents indicating that they wanted this, based on responses from patients in the waiting rooms of GP practices in Western Norway. Significant findings are highlighted.

| Wanted guidance (%) | Unadjusted odds ratio (95 % CI) | Adjusted1 odds ratio (95 % CI) (n = 1 850) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | (n = 1999) | |||

| 18–29 | 60 | 1 | 1 | |

| 30–39 | 58 | 0.90 (0.66 to 1.24) | 1.01 (0.69 to 1.47) | |

| 40–49 | 57 | 0.87 (0.63 to 1.21) | 0.87 (0.58 to 1.30) | |

| 50–59 | 54 | 0.78 (0.56 to 1.08) | 0.64 (0.43 to 0.98) | |

| 60–69 | 57 | 0.87 (0.63 to 1.20) | 0.74 (0.48 to 1.12) | |

| 70+ | 51 | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.94) | 0.56 (0.36 to 0.86) | |

| Sex | (n = 1 953) | |||

| Female | 53 | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 60 | 1.34 (1.11 to 1.62) | 1.41 (1.15 to 1.73) | |

| Do you have children of your own? | (n = 1 940) | |||

| No | 60 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 54 | 0.80 (0.65 to 0.98) | 0.80 (0.60 to 1.05) | |

| Country of birth | (n = 1 975) | |||

| Norway | 56 | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 56 | 1.00 (0.76 to 1.31) | 0.98 (0.72 to 1.32) | |

| Highest completed education | (n = 1961) | |||

| Primary/lower secondary school | 67 | 1 | 1 | |

| Upper secondary school or vocational school | 59 | 0.70 (0.49 to 0.99) | 0.68 (0.46 to 0.99) | |

| University/university college | 50 | 0.49 (0.34 to 0.70) | 0.51 (0.34 to 0.74) | |

| I want to lose weight | (n = 1 980) | |||

| No | 41 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 65 | 2.67 (2.22 to 3.22) | 2.62 (2.14 to 3.20) | |

| Medication use | (n = 2 006) | |||

| No | 53 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 60 | 1.33 (1.11 to 1.59) | 1.42 (1.11 to 1.81) | |

1Adjusted for the other variables in the table.

When adjusting for a desire to lose weight and medication use, younger patients were more likely than older patients to have raised the subject of diet and how this affects their health (Table 4). There was no disparity between men and women, while patients without children were more likely than those with children to have raised the subject of diet with their GP.

Table 4

Probability (odds ratio and 95 % confidence interval (CI)) of having previously raised the subject of diet with a GP, and proportion (%) who responded that they had done this, based on responses from patients in the waiting rooms of GP practices in Western Norway. Significant findings are highlighted.

| Had raised the subject of diet with GP | Unadjusted odds ratio (95 % CI) | Adjusted1 odds ratio (95 % CI) (n = 1 732) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | (n = 1 890) | |||

| 18–29 | 35 | 1 | 1 | |

| 30–39 | 33 | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.32) | 1.03 (0.69 to 1.54) | |

| 40–49 | 38 | 1.13 (0.80 to 1.60) | 1.10 (0.72 to 1.67) | |

| 50–59 | 37 | 1.10 (0.78 to 1.56) | 0.97 (0.63 to 1.51) | |

| 60–69 | 30 | 0.81 (0.57 to 1.15) | 0.67 (0.42 to 1.06) | |

| 70+ | 27 | 0.68 (0.49 to 0.96) | 0.49 (0.30 to 0.78) | |

| Sex | (n = 1 847) | |||

| Female | 32 | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 34 | 1.12 (0.92 to 1.37) | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.29) | |

| Do you have children of your own? | (n = 1 837) | |||

| No | 38 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ja | 31 | 0.73 (0.59 to 0.92) | 0.70 (0.52 to 0.93) | |

| Country of birth | (n = 1 869) | |||

| Norway | 32 | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 39 | 1.34 (1.00 to 1.78) | 1.18 (0.86 to 1.61) | |

| Highest completed education | (n = 1 855) | |||

| Primary/lower secondary school | 30 | 1 | 1 | |

| Upper secondary school or vocational school | 33 | 1.15 (0.80 to 1.67) | 1.15 (0.76 to 1.72) | |

| University/university college | 33 | 1.11 (0.77 to 1.62) | 1.21 (0.80 to 1.82) | |

| I would like to lose weight | (n = 1 852) | |||

| No | 26 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 37 | 1.67 (1.36 to 2.05) | 1.44 (1.16 to 1.80) | |

| Medication use | (n = 1889) | |||

| No | 29 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 38 | 1.49 (1.22 to 1.80) | 2.13 (1.63 to 2.77) | |

1Adjusted for the other variables in the table.

Patients who wanted to lose weight or who used medication for a chronic condition were more likely to have raised the subject of diet with their GP, and patients using medication for a chronic condition were most likely to have done so (odds ratio 2.13; 95 % CI 1.63 to 2.77).

Discussion

In this survey, we found that even though more than half of the patients wanted the subject of diet to be raised, only one-third indicated that they had raised the subject in a GP consultation. Among patients using medication for a chronic condition, 60 % reported wanting advice on how diet affects their health. There is ample evidence that dietary interventions have potential in such contexts (1–11). Nevertheless, only 38 % of these patients had raised the subject of diet. We found a significantly higher proportion of patients who wanted dietary guidance among younger patients, men, those with a lower level of education, patients who wanted to lose weight and patients using medication for a chronic condition.

Two out of five reported being confused by diet and dietary advice. Meanwhile, only 4 % reported lacking the necessary knowledge. A population survey conducted by Norstat showed that only 59 % of respondents were aware of the Norwegian Directorate of Health's dietary advice (17, p. 44). This suggests a possible need in the population for more evidence-based information about diet.

Despite the goal of the Coordination Reform for GPs to play a more active role in preventive health care (12), there has been a decline in preventive efforts among GPs in Norway (18). An increasing proportion of the population is also receiving preventive pharmacotherapy for cardiovascular diseases (19). These patients are candidates for targeted information about the benefits of a healthy diet as an alternative or supplement to medication (9). Based on a range of recommended guidelines, GPs must prioritise which interventions and guidelines are most relevant for different patients (20).

Around 60 % of the study participants reported wanting to lose weight. The proportion of men and women with overweight or obesity (BMI > 25) in Norway in 2020 was 59 % and 47 %, respectively (21). A qualitative study based on interviews with eight adults with overweight found that they wanted their GP to raise the subject of overweight, but experienced that the GP either did not do this, quickly closed down discussion on the subject, or simplified the problem (13). The interviewees also had an expectation that GPs would be knowledgeable about overweight and measures for weight regulation, as well as a shared responsibility for helping to prevent negative weight development.

Our findings pointed towards patient groups who were more likely to consider diet an important subject and who may be more receptive to guidance (22). Participants with a lower level of education wanted more information about diet. Focussing on this group can help reduce social inequalities, as those with a higher level of education tend to have a healthier diet (17). Men were more likely to want dietary guidance than women. This should be viewed in light of the fact that morbidity and mortality rates are higher for men as a whole.

The 83 % response rate was a strength of our study, and we can consider the study population to be representative of adults in GP consultations. Anonymous data collection reduced the risk of various response biases (23). Sensitivity analyses indicated robust findings (results not shown).

A weakness of the study was the use of non-validated questions/questionnaires, where, for example, the order of the questions may have influenced the responses (24). Furthermore, the concept of diet was not defined in the patient information or in the questionnaire and was open to individual interpretation. Another limitation of the study was that we cannot know if there was alignment between those who wanted dietary guidance and those who needed it. Language problems may have been a barrier to participation. Any disparities between different migrant groups were not captured in the study.

We found that many patients were concerned about diet, and half wanted guidance on how diet affects health. However, only one-third reported raising the subject of diet in their GP consultation. In addition, the majority reported a desire to lose weight. The desire to receive dietary guidance was more common among younger patients, men, those with a lower level of education, those who wanted to lose weight and those who used medication for a chronic condition. Such knowledge can be useful for primary healthcare providers to determine when a focus on diet can be particularly beneficial.

The article is based on a student paper at the University of Bergen.

Thanks go to Kine Marie Fleime Møll, Kasper Olsen and Erlend Nåmdal for practical facilitation, and to Khadra Yasien Ahmed for translating the questionnaire into English. The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Iqbal K et al. Food groups and intermediate disease markers: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2018; 108: 576–86. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

Fadnes LT, Økland JM, Haaland OA et al. Estimating impact of food choices on life expectancy: A modeling study. PLoS Med 2022; 19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003889. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Lampousi AM et al. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2017; 32: 363–75. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G et al. Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2017; 105: 1462–73. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Bechthold A, Boeing H, Schwedhelm C et al. Food groups and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke and heart failure: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019; 59: 1071–90. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019; 393: 1958–72. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

WHO. Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight Accessed 1.5.2023.

- 8.

Schlesinger S, Neuenschwander M, Schwedhelm C et al. Food Groups and Risk of Overweight, Obesity, and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Adv Nutr 2019; 10: 205–18. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Helsedirektoratet. Legemidler ved primærforebygging av hjerte- og karsykdom. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/forebygging-av-hjerte-og-karsykdom/legemidler-ved-primaerforebygging-av-hjerte-og-karsykdom#legemiddelbehandling-avhoyt-blodtrykk-praktisk-informasjon Accessed 8.11.2023.

- 10.

Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): Lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 3230–6. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018; 391: 541–51. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

St.meld. nr. 47 (2008-2009). Samhandlingsreformen. Rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-47-2008-2009-/id567201/?ch=1 Accessed 1.2.2024.

- 13.

Juvik LA, Eldal K, Sandvoll AM. Personar med overvekt sine erfaringar i møte med fastlegen – ein kvalitativ studie. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2023; 143. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.22.0528. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Michie S. Talking to primary care patients about weight: a study of GPs and practice nurses in the UK. Psychol Health Med 2007; 12: 521–5. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Gimenez L, Kelly-Irving M, Delpierre C et al. Interaction between patient and general practitioner according to the patient body weight: a cross-sectional survey. Fam Pract 2023; 40: 218–25. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Nilsen L. Medisinstudenter i allmennpraksis innhenter forskningsdata. https://www.legeforeningen.no/om-oss/fond-og-legater/allmennmedisinsk-forskningsfond/forskningsnytt/medisinstudenter-i-allmennpraksis-innhenter-forskningsdata/ Accessed 2.11.2023.

- 17.

Helsedirektoratet. Utviklingen i norsk kosthold 2022. Rapport IS-3054. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/utviklingen-i-norsk-kosthold/Utviklingen%20i%20norsk%20kosthold%202022%20-%20Kortversjon.pdf/_/attachment/inline/b8079b0a-fefe-4627-8e96-bd979c061555:e22da8590506739c4d215cfdd628cfaaa3b2dbc8/Utviklingen%20i%20norsk%20kosthold%202022%20-%20Kortversjon.pdf Accessed 29.11.2023.

- 18.

Schäfer WL, Boerma WG, Spreeuwenberg P et al. Two decades of change in European general practice service profiles: conditions associated with the developments in 28 countries between 1993 and 2012. Scand J Prim Health Care 2016; 34: 97–110. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 19.

Danise LS, Bakken GV, Henjum K et al. Legemiddelforbruket i Norge 2018-2022. Data fra Grossistbasert legemiddelstatistikk.https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/856ff0c333114637a14978f135803d60/legemiddelforbruket-i-norge-2018-til-2022.pdf Accessed 5.11.2023.

- 20.

Johansson M, Guyatt G, Montori V. Guidelines should consider clinicians' time needed to treat. BMJ 2023; 380. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072953. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 21.

Abel MH, Totland TH. Kartlegging av kostholdsvaner og kroppsvekt hos voksne i Norge basert på selvrapportering – Resultater fra Den nasjonale folkehelseundersøkelsen 2020. https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/2021/rapport-nhus-2020.pdf Accessed 8.11.2023.

- 22.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51: 390–5. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Fadnes LT, Taube A, Tylleskar T. How to identify information bias due to self-reporting in epidemiological research. Internet Journal of Epidemiology 2009; 7: 1–9.

- 24.

Schwarz N. Self-reports: How the questions shape the answers. Am Psychol 1999; 54: 93–105. [CrossRef]