MAIN FINDINGS

At St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim, 30-day mortality after emergency laparotomy was 8.2 % in the period between 1 January 2015 and 1 April 2020.

Emergency surgery was performed within the scheduled timeframe for 83.9 % of patients.

Emergency laparotomies are associated with higher mortality, more postoperative complications, and longer hospital stays than elective laparotomies (1–4). The most common abdominal surgical conditions requiring emergency laparotomy are perforation and obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract (5).

In recent years, much has been done to improve the outcomes of elective surgery, whereas similar progress has yet to be made for emergency surgery (6). In 2012, the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit launched an extensive project in England and Wales aimed at improving the management of patients undergoing emergency laparotomy (7). For hospitals in England and Wales that wish to offer emergency laparotomy it is now mandatory to record process measures and outcomes for all such surgeries performed. Around 25 000 patients are included in this registry each year, and it is now the most comprehensive registry for emergency laparotomies in Europe (8, 9). By identifying risk factors and optimising internal hospital procedures, 30-day postoperative mortality was reduced from 11.8 % to 9.3 % for this patient group over a five-year period (8).

Few studies have examined emergency laparotomies in Scandinavian patient datasets (10). The purpose of this study was to survey patient characteristics, hospital care pathways, and mortality for patients undergoing emergency laparotomies at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients over 18 years of age who underwent emergency laparotomy or laparoscopy at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim, in the period between 1 January 2015 and 1 April 2020. Inclusion and exclusion criteria from the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (8,11) were applied (Box 1).

Key criteria, shown below, were taken from the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (11).

Inclusion criteria:

Patients over 18 years of age who underwent emergency surgery (scheduled for within 6, 24 or 72 hours) in the stomach, small intestine, large intestine and/or rectum for ischaemia, bleeding, perforation, obstruction or infection/abscess, at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim

Emergency revision surgery for complications of elective gastrointestinal surgery

Exclusion criteria:

Patients under 18 years of age

Patients who underwent surgery at Røros or Orkdal Hospitals

Elective surgery

Surgery for primary pathology of the oesophagus, spleen, kidneys or urinary tract, gallbladder, biliary tract, liver or pancreas

Surgery with appendicitis as the primary indication

Surgery due to injury or trauma

Surgery for gynaecological or vascular conditions

Patients were identified using St Olav's Hospital's operation planning system (Op-Plan). Patients over 18 years of age who were scheduled to undergo emergency surgery within 6, 24 or 72 hours, on the basis of St Olav's Hospital guidelines (see Appendix 1), were considered for inclusion in the study. Procedures with codes related to the digestive system and spleen according to the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP) (12) and that potentially met the inclusion criteria (see Appendix 2) were considered for inclusion. Information on these patients was reviewed manually by searching the hospital's electronic medical records system, DocuLive.

Patient and surgery characteristics, date of death, and information on the hospital care pathway were retrieved from the hospital's electronic medical records system. Patient characteristics included age, sex, body mass index, number of regular medications, smoking status, preoperative cardiovascular and respiratory status, preoperative ECG, ASA classification, and any history of abdominal surgery, here defined as all previous operations involving opening of the abdominal cavity. The patient's preoperative ECG was categorised as: no abnormality; atrial fibrillation with frequency 60–90 beats/min; and atrial fibrillation with frequency over 90 beats/min. Cardiovascular status was classified as: no heart failure; use of diuretics or antihypertensives; use of anticoagulants or presence of peripheral oedema; and cardiomegaly. Respiratory status was categorised as: no dyspnoea; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) stage 1–2; COPD stage 3; and COPD stage 4. To determine whether the surgeon and assistant(s) were specialty registrars or specialists in gastrointestinal surgery, the dates of any relevant specialist qualifications were retrieved from the health personnel registry and compared to the date of surgery.

The primary indication for surgery was established based on information in the medical records, the operation note, and diagnosis codes at discharge. In cases with more than one indication, the primary indication was assigned in the following order: 1) ischaemia, 2) perforation, 3) bleeding, 4) obstruction, 5) infection/abscess, and 6) other. 'Other' includes operations that could not be clearly defined as due to indications 1–5, but which were nevertheless encompassed by the more specific inclusion criteria of the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit, such as laparotomy due to major abdominal wound dehiscence (11). Malignancy was graded according to the TNM classification system (13). Cancers with direct attachment to intra- and/or retroperitoneal organs at the time of surgery were categorised as abdominal.

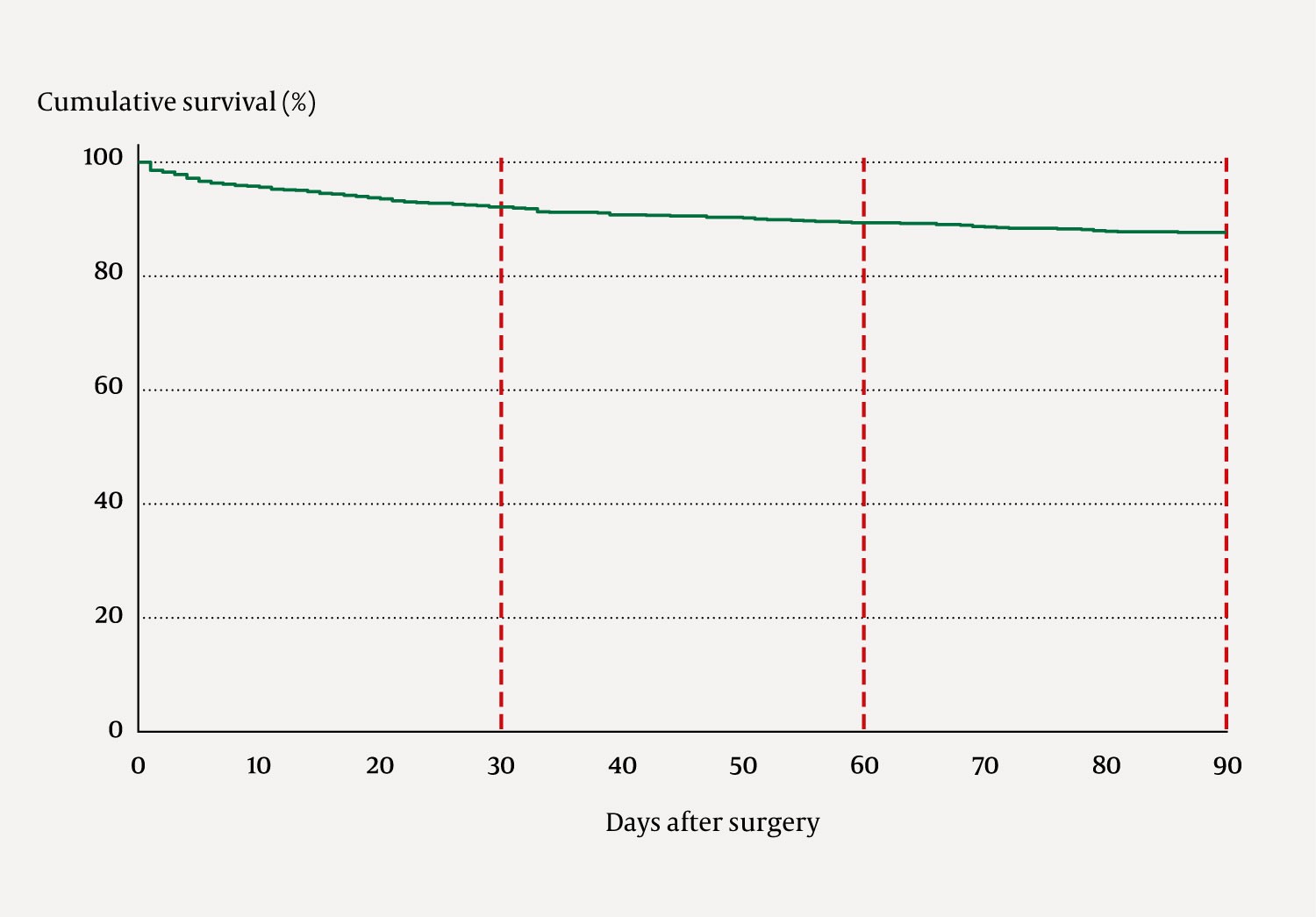

Observed postoperative mortality at 72 hours, and at 30, 60 and 90 days, was calculated based on the date of death. Mortality was presented as a Kaplan-Meier survival curve. The number of patients with missing data for each characteristic was recorded. Data were analysed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC College Station, TX, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

Representatives of the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics Central Norway (REK Central) considered the project to be a quality assurance study and thus outside their remit. The data protection officer and the head of the Surgical Clinic at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim, found no grounds for a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA). The data were stored in an encrypted domain, accessible only to those involved in the project.

Results

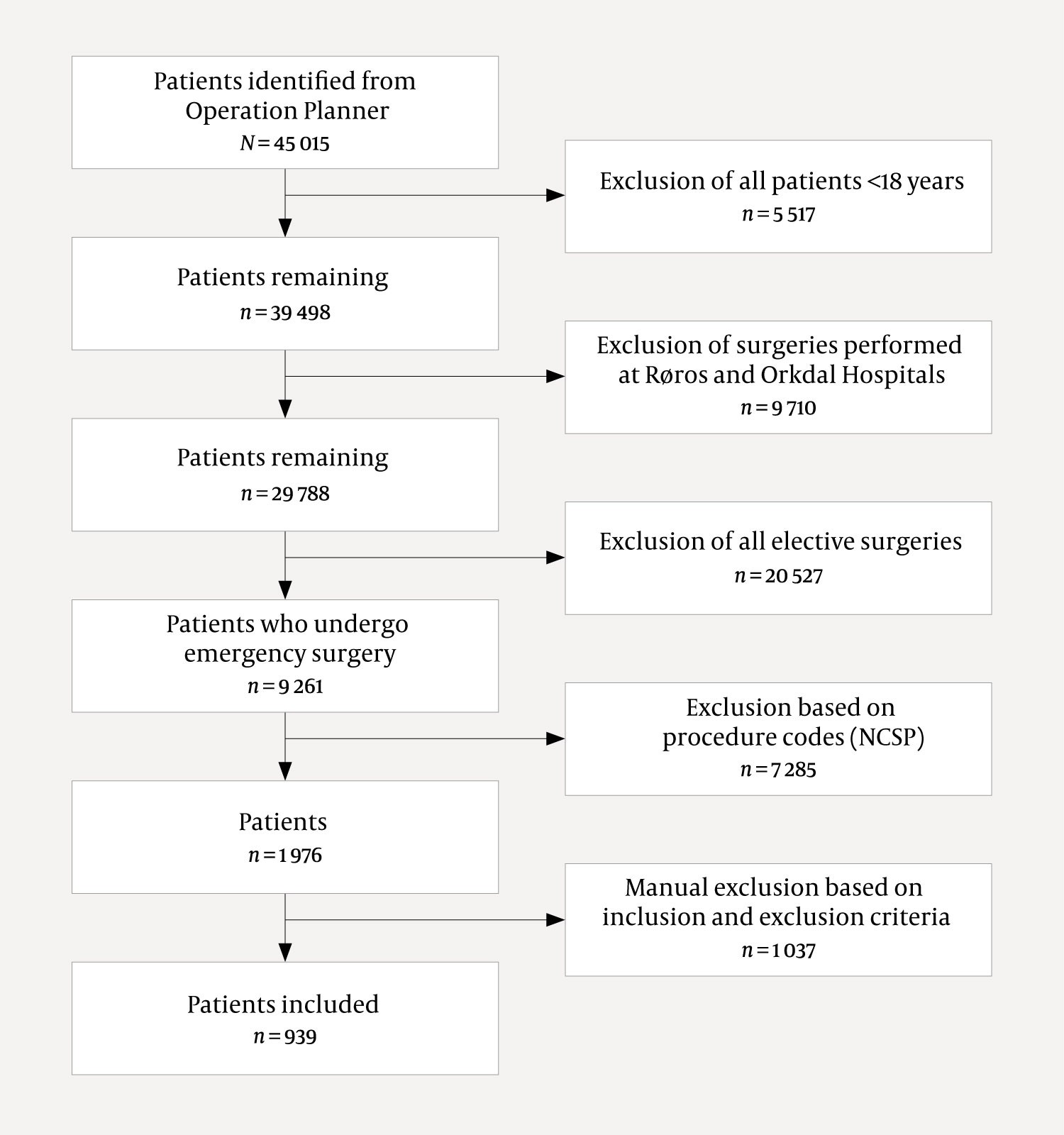

A total of 45 015 patients underwent surgery at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim, in the period from 1 January 2015 to 1 April 2020. Of these, 5 517 patients were excluded because they were under the age of 18. A further 9 710 surgeries were excluded because they were performed at Orkdal and Røros Hospitals, and another 20 527 were excluded because they were elective. Following selection based on procedures codes, a total of 1 976 patients remained. Of these, 939 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1), of whom 891 (94.9 %) had undergone laparotomy and 48 (5.1 %) laparoscopic surgery.

The median (interquartile range) age of the patients included was 68 years (54–76). The observed 30-day mortality was 8.5 % for women and 7.9 % for men (Table 1). Mortality increased with age and was highest for the age group 80 years and above (16.6 %). Patients who underwent surgery based on a primary indication of ischaemia had the highest 30-day mortality (17.7 %), followed by those whose primary indication for surgery was perforation (12.7 %) (Table 2). For patients with atrial fibrillation with a ventricular rate above 90 beats per minute, 30-day mortality was 19.0 %.

Table 1

Characteristics of patients who underwent acute laparotomies and laparoscopies at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim, between January 2015 and April 2020. Number (n) and percentage (%).

|

| All patients, n (%) | 30-day mortality n (%)1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 939 (100) | 77 (8.2) | ||

| Age group (years) |

|

| ||

|

| 18–39 | 83 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

| 40–49 | 84 (9.0) | 1 (1.2) | |

|

| 50–59 | 134 (14.3) | 2 (1.5) | |

|

| 60–69 | 209 (22.3) | 19 (9.1) | |

|

| 70–79 | 248 (26.4) | 25 (10.1) | |

|

| 80+ | 181 (19.3) | 30 (16.6) | |

| Sex |

|

| ||

|

| Female | 483 (51.4) | 41 (8.5) | |

|

| Male | 456 (48.6) | 36 (7.9) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) |

|

| ||

|

| < 18.5 (underweight) | 62 (6.9) | 8 (12.9) | |

|

| 18.5–24.9 (normal weight) | 413 (45.7) | 42 (10.2) | |

|

| 25.0–29.9 (overweight) | 284 (31.5) | 16 (5.6) | |

|

| 30.0–34.9 (obesity) | 90 (10.0) | 4 (4.4) | |

|

| ≥ 35 (severe obesity) | 54 (6.0) | 1 (1.9) | |

|

| Missing data | 36 |

| |

| Previous abdominal surgery |

|

| ||

|

| Yes | 641 (68.3) | 46 (7.2) | |

|

| No | 298 (31.7) | 31 (10.4) | |

| Number of regular medications |

|

| ||

|

| 0 | 170 (18.1) | 4 (2.4) | |

|

| 1–3 | 292 (31.1) | 11 (3.8) | |

|

| 4–6 | 226 (24.1) | 22 (9.7) | |

|

| 7–9 | 157 (16.7) | 20 (12.7) | |

|

| 10+ | 94 (10.0) | 20 (21.3) | |

| Smoker2 |

|

| ||

|

| Yes | 188 (22.5) | 16 (8.5) | |

|

| No | 648 (77.5) | 39 (6.0) | |

|

| Missing data | 103 |

| |

| Preoperative ECG |

|

| ||

|

| No abnormality | 838 (89.2) | 61 (7.3) | |

|

| Atrial fibrillation, 60–90 beats/min | 22 (2.3) | 1 (4.6) | |

|

| Atrial fibrillation, > 90 beats/min | 79 (8.4) | 15 (19.0) | |

| Cardiovascular status |

|

| ||

|

| No heart failure | 503 (53.6) | 22 (4.4) | |

|

| Diuretics or antihypertensives | 343 (36.5) | 40 (11.7) | |

|

| Peripheral oedema/anticoagulants | 90 (9.6) | 13 (14.4) | |

|

| Cardiomegaly | 3 (0.3) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Respiratory status |

|

| ||

|

| Ingen dyspnoea | 773 (82.3) | 53 (6.9) | |

|

| COPD stage 1–2 | 115 (12.3) | 12 (10.4) | |

|

| COPD stage 3 | 37 (3.9) | 9 (24.3) | |

|

| COPD stage 4 | 14 (1.5) | 3 (21.4) | |

| ASA classification |

|

| ||

|

| ASA class 1 | 10 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

| ASA class 2 | 187 (19.9) | 1 (0.5) | |

|

| ASA class 3 | 493 (52.6) | 21 (4.3) | |

|

| ASA class 4 | 241 (25.7) | 51 (21.2) | |

|

| ASA class 5 | 7 (0.8) | 4 (57.1) | |

|

| Missing data | 1 |

| |

| Malignant disease stage |

|

| ||

|

| Intra-abdominal cancer |

|

| |

|

|

| None | 647 (68.9) | 32 (5.0) |

|

|

| T1 - 4N0M0 | 50 (5.3) | 3 (6.0) |

|

|

| T1 - 4N1 - 3M0 | 50 (5.3) | 4 (8.0) |

|

|

| T1 - 4N0 - 3M1 | 154 (16.4) | 32 (20.8) |

|

| Extra-abdominal cancer | 38 (4.1) | 6 (15.8) | |

1Percentage of each subgroup

2Patient is an active smoker at the time of surgery, stated in the medical records

Table 2

Surgical characteristics for acute laparotomies and laparoscopies performed at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim, between January 2015 and April 2020. Number (n) and percentage (%).

|

|

|

| All patients, n (%) | 30-day mortality n (%)1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 939 (100) | 77 (8.2) | ||

| Underwent preoperative CT scan |

|

| ||

|

| Yes | 828 (88.2) | 64 (7.7) | |

|

| No | 111 (11.8) | 13 (11.7) | |

| Primary indication |

|

| ||

|

| Ischaemia | 85 (9.1) | 15 (17.7) | |

|

| Perforation | 220 (23.4) | 28 (12.7) | |

|

| Bleeding | 51 (5.4) | 4 (7.8) | |

|

| Obstruction | 488 (52.0) | 28 (5.7) | |

|

| Infection/abscess | 18 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

| Other | 77 (8.2) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Time at which surgery began |

|

| ||

|

| 00:00–07:59 | 136 (14.5) | 13 (9.6) | |

|

| 08:00–11:59 | 247 (26.3) | 12 (4.9) | |

|

| 12:00–17:59 | 309 (32.9) | 29 (9.4) | |

|

| 18:00–23:59 | 247 (26.3) | 23 (9.3) | |

| Surgical specialisation level2 |

|

| ||

|

| Specialist |

|

| |

|

|

| Gastroenterological surgery | 456 (48.6) | 40 (8.8) |

|

|

| General surgery | 141 (15.0) | 11 (7.8) |

|

|

| Other specialisation | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| Non-specialist | 338 (36.0) | 26 (7.7) | |

1Percentage of each subgroup

2Surgical specialisation status of registered personnel present during surgery

The observed postoperative mortality for the entire patient population was 2.6 % after 72 hours, 8.2 % after 30 days, 11.0 % after 60 days, and 12.7 % after 90 days (Figure 2). The median postoperative hospital stay was 10 days (interquartile range 6–18) while the mean was 14.5 days (SD 14.2). A total of 75 patients (8 %) were discharged to local hospitals for further treatment.

Emergency surgery was performed within the timeframe scheduled for 788 (83.9 %) patients. Overall, 734 patients (78.2 %) were scheduled to undergo emergency surgery within 6 hours, and 187 (19.9 %) within 24 hours, and these targets were met for 629 (85.7 %) and 145 (77.5 %) individuals, respectively. A preoperative CT scan was performed for 828 patients (88.2 %). At least one certified surgical specialist was present during the procedure for 601 patients (64.0 %).

Discussion

One of the objectives of this study was to examine the mortality rate for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim. In our patient material, the observed 30-day mortality rate was 8.2 %. In comparison, a systematic review of 33 studies of emergency laparotomy and laparoscopy found that 30-day mortality ranged from 0 % to 24%; Danish hospitals were among those with the highest mortality rates, with an average of 13.9 % (10).

Comparing studies on emergency laparotomy is challenging because both the surgeries and the patients themselves are highly heterogeneous. Differences in study inclusion criteria make it difficult to compare results between hospitals or countries, or over time. In our study, we therefore used the inclusion criteria from the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit, in which 30-day mortality was reported to be 9.3 % (8, 11).

The average postoperative stay at St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim, was 14.5 days, while the corresponding figure in the 2019 Sixth Patient Report of the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit, which included 24 823 patients, was 15.4 days. The shorter length of stay in our dataset was observed despite the fact that St Olav's Hospital had a higher proportion of patients with intra-abdominal cancer (27 % vs. 19 %), more patients over 65 years of age (60 % vs. 56 %), and more patients in higher ASA classes (26 % vs. 18 % with ASA class 4 or 5) (8).

In a Danish study with almost identical inclusion criteria, patients also tended to be in lower ASA classes than the patients at St. Olav's Hospital (1). One possible explanation may be differences in the way anaesthesiologists at St Olav's Hospital assign patients to ASA classes compared to their counterparts at hospitals in England, Wales and Denmark. It may also be that patients at St Olav's Hospital have a higher disease burden than patients at hospitals in England and Wales, as indicated by the higher proportion of patients with malignant disease in the current study (8). Although caution is required in drawing conclusions based on a retrospective review, our results suggest somewhat greater survival and shorter length of hospital stay for patients at St Olav's Hospital compared with international data.

This study has also identified areas that could be targeted by the Surgical Clinic at St Olav's Hospital to further reduce postoperative mortality after acute laparotomy. Early surgery is important to increase survival rates (14, 15). Among patients who were scheduled to undergo emergency surgery within 6 hours, 85.7 % were operated on within this timeframe, thereby meeting the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit's recommended minimum standard of 85 % (8). The Surgical Clinic aims for at least 90 % of patients scheduled for surgery within 6 or 24 hours to undergo surgery within the specified timeframe. Patients undergoing emergency laparotomies are often vulnerable elderly patients with multimorbidity, a group with high mortality risk. It is therefore necessary to identify, prior to surgery, those patients with the highest risk of death. Decisions can then be made collectively regarding the most suitable treatment level and surgical strategy, and on securing early access to surgery. Sufficient access to emergency operating theatres and personnel has been identified as one of the most important factors for good emergency surgery provision (16).

Hospitals that participated in the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit reduced their 30-day mortality from 11.8 % in 2013 to 9.3 % in 2019. The greatest reduction in mortality was in patients over the age of 65. This was due to improved identification of high-risk patients through measures such as the use of risk calculators for acute laparotomy (8). Requirements have also been introduced for senior consultants in anaesthesiology and surgery to be involved in pre- and perioperative care for high-risk patients. Compliance is assessed by measuring the percentage of such patients that are managed by senior consultants. Access to planned postoperative intensive care has also been improved for high-risk patients.

Finally, geriatricians are now involved to a greater degree in assessing vulnerability in the oldest patients (8). This may have led to greater use of conservative and palliative approaches rather than attempts at curative surgery. These factors are likely to be relevant not only to St Olav's Hospital but also to other Norwegian hospitals that perform emergency surgery. An essential prerequisite for implementing measures such as these is that data on the management and outcomes of this patient population are reviewed, discussed, and form the basis for any changes.

A strength of this study is that, with few exceptions, it features complete data on a well-defined group of patients, which reduces the possibility of selection bias. A weakness of the retrospective study design is that it is based on information in medical records. This made classification of multimorbidity in particular challenging, as information on this topic in the medical records was often incomplete.

This article had been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Tengberg LT, Cihoric M, Foss NB et al. Complications after emergency laparotomy beyond the immediate postoperative period - a retrospective, observational cohort study of 1139 patients. Anaesthesia 2017; 72: 309–16. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

Howes TE, Cook TM, Corrigan LJ et al. Postoperative morbidity survey, mortality and length of stay following emergency laparotomy. Anaesthesia 2015; 70: 1020–7. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Vester-Andersen M, Lundstrøm LH, Møller MH et al. Mortality and postoperative care pathways after emergency gastrointestinal surgery in 2904 patients: a population-based cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 860–70. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Liljendahl MS, Gögenur I, Thygesen LC. Emergency Laparotomy in Denmark: A Nationwide Descriptive Study. World J Surg 2020; 44: 2976–81. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Barrow E, Anderson ID, Varley S et al. Current UK practice in emergency laparotomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013; 95: 599–603. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

Stewart B, Khanduri P, McCord C et al. Global disease burden of conditions requiring emergency surgery. Br J Surg 2014; 101: e9–22. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

National Emergency Laparotomy Audit. About the Audit: Background. https://www.nela.org.uk/NELA_Background Accessed 9.5.2021.

- 8.

National Emergency Laparotomy Audit. Sixth Patient NELA Report. https://www.nela.org.uk/Sixth-Patient-Report#pt Accessed 9.5.2021.

- 9.

Kiernan AC, Waters PS, Tierney S et al. Mortality rates of patients undergoing emergency laparotomy in an Irish university teaching hospital. Ir J Med Sci 2018; 187: 1039–44. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Fagan G, Barazanchi A, Coulter G et al. New Zealand and Australia emergency laparotomy mortality rates compare favourably to international outcomes: a systematic review. ANZ J Surg 2021; 91: 2583–91. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

National Emergency Laparotomy Audit. Audit Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria. https://www.nela.org.uk/Criteria#pt Accessed 30.5.2021.

- 12.

Direktoratet for e-helse. NCMP, NCSP og NCRP. https://finnkode.ehelse.no/#ncmpncsp/0/0/0/-1 Accessed 6.6.2021.

- 13.

Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

- 14.

Buck DL, Vester-Andersen M, Møller MH. Surgical delay is a critical determinant of survival in perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg 2013; 100: 1045–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Huddart S, Peden CJ, Swart M et al. Use of a pathway quality improvement care bundle to reduce mortality after emergency laparotomy. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 57–66. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Kinnear N, Britten-Jones P, Hennessey D et al. Impact of an acute surgical unit on patient outcomes in South Australia. ANZ J Surg 2017; 87: 825–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]