Cryopreservation and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue is a fertility-preserving treatment offered to prepubertal girls and women of reproductive age who are at risk of developing premature ovarian insufficiency (1). The treatment is offered at specialist centres in more than 20 different countries (2). In many countries removal of ovarian tissue is offered at several centres, while cryopreservation, storage and autotransplantation is undertaken mainly at a selected few centres (3, 4).

One of the most frequent causes of premature ovarian insufficiency is gonadotoxic therapy – chemotherapy and radiotherapy – during cancer treatment. The ovaries are particularly sensitive to alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide, busulfan, dacarbazine and procarbazine (5, 6). Patients who are to undergo haematopoietic stem cell transplantation are at particularly high risk of developing premature ovarian insufficiency due to the conditioning regimen, which consists of high-dose treatment with alkylating agents and total body irradiation (5). Other causes of premature ovarian insufficiency include benign haematological disorders, autoimmune conditions and genetic conditions, which, in themselves or by virtue of the treatment required (cytostatic therapy or stem cell transplantation) increase the risk of premature ovarian insufficiency.

Reproductive ability can be preserved through cryopreservation of oocytes, embryos or ovarian tissue. The method chosen is contingent on the patient's age, risk of premature ovarian insufficiency and how quickly the treatment needs to commence (7). For prepubertal girls and women whose treatment must be initiated rapidly, cryopreservation of ovarian tissue is the only option to preserve fertility, but specific criteria must be used for selection of patients (8, 9).

Ovarian tissue is harvested laparoscopically by removing one ovary or by taking biopsies of one or both ovaries. The cortical tissue is then frozen in small fragments. If the patient is in remission from their condition after treatment is completed, and has developed premature ovarian insufficiency, the ovarian tissue can be transplanted autologously to the remaining ovary or to the pelvic wall. When endocrine function is restored, the woman has the possibility of becoming pregnant spontaneously or by assisted reproductive technology. Autotransplantation of frozen ovarian tissue has been reported from 21 different countries, and in 2018 a total of 360 autotransplantations were performed in 318 patients (2). A number of studies point to pregnancy rates of 20–30 % after autotransplantation of ovarian tissue (10–12), and more than 130 live births following autotransplantation of ovarian tissue have been reported worldwide (2, 13).

The Nordic countries have chosen different principles for organising the cryopreservation of ovarian tissue. In Sweden and Finland, the procedure is regional, whereas in Denmark and Norway it is centralised at a national level (14). In Norway, fertility-preserving cryopreservation of ovarian tissue had been authorised since 2004, and the treatment is centralised at Oslo University Hospital, which has a nationwide function with regard to cryopreservation, storage and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue (15, 16). A total of 236 patients have undergone cryopreservation of ovarian tissue at Oslo University Hospital, and 30 autotransplantations have been performed between 2004, when the procedure was initiated, and 2020, whereby seven of the patients succeeded in becoming pregnant and eight children were born (T. Tanbo, personal communication, March 2021).

The main criteria for offering patients cryopreservation and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue remain controversial, and the aim of this study was therefore to shed more light on which patients are offered this treatment.

Material and method

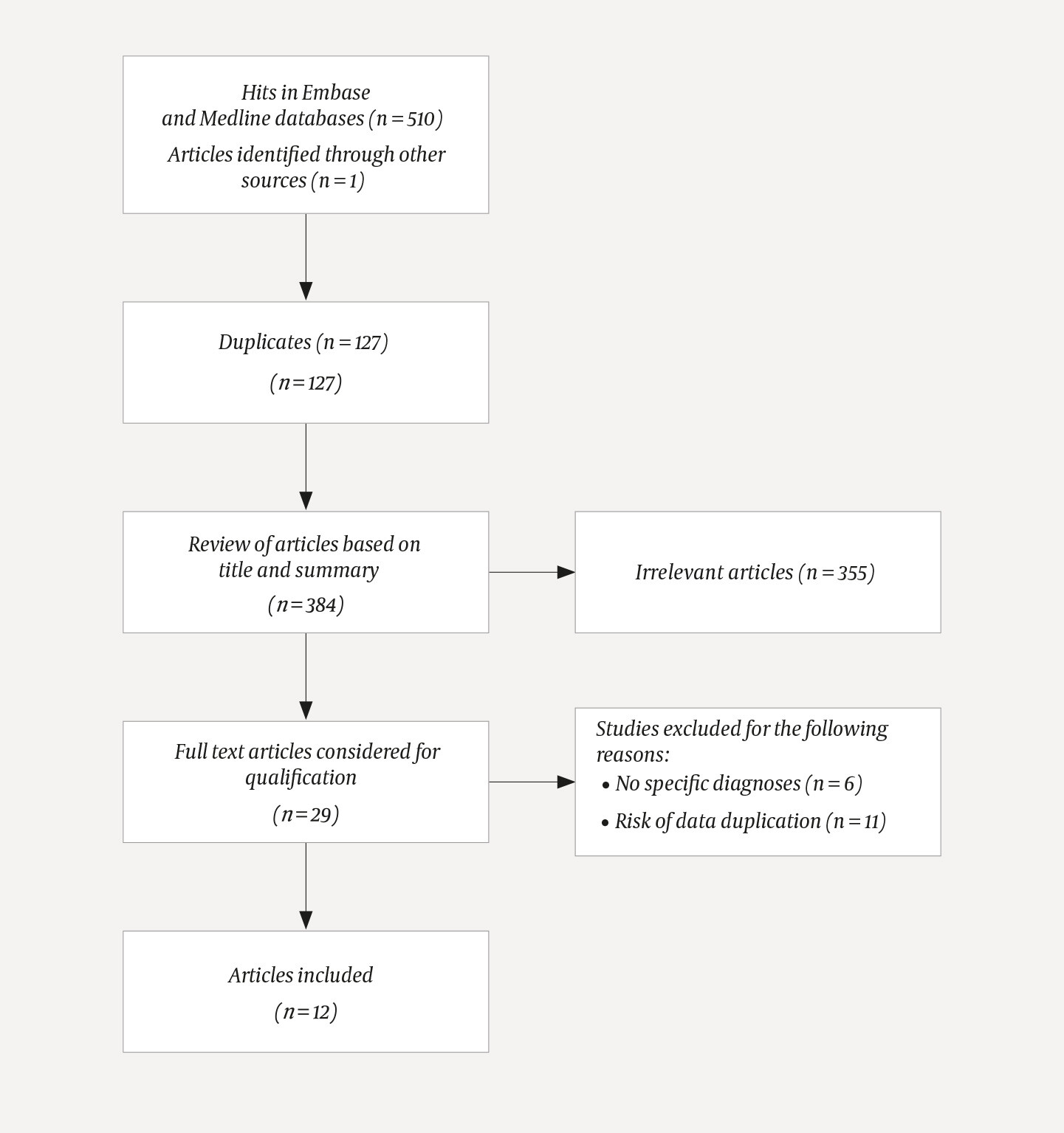

We conducted a search in the Embase and Medline databases with the keywords 'cryopreservation', 'transplantation' and 'ovary' as well as the free text words 'cryopreservation', 'transplantation', 'ovary', 'fertility preservation', 'cryopreserved ovarian tissue' and 'ovarian tissue cryopreservation in various combinations (see Appendix 1). The search was concluded on 16 June 2021 and was limited to articles published after 1 January 2010. A total of 511 articles were reviewed. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the literature search.

Title and abstract were assessed in 384 articles in order to find studies with indications for cryopreservation and/or autotransplantation of ovarian tissue. Animal experiments and studies that did not present specific diagnoses, and where indications were not central to the summary, were excluded. Articles not written in English (n = 1), articles that were only available as conference papers (n = 21), and articles to which the library had no full-text access (n =2), were excluded. Case studies were excluded to reduce the risk of data duplication. All the authors of this article have read the summaries, but the final selection was made by Gjeterud and Fedder.

A total of 29 articles were read in full text. Altogether 17 articles were excluded due to the absence of specific diagnoses or the risk of data duplication, also including systematic review articles and meta-analyses (see Appendix 2). Some review articles had been based on previously published studies and also presented results from the authors' own studies. We included only primary studies with indications of diagnoses. After exclusion of the above, 12 articles were included (Table 1) (3, 12, 15, 17)(17–25).

Table 1

Overview of included studies with specified indications for cryopreservation and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue.

| Reference | Cryopreservation, number of patients | Most frequent diagnoses for cryopreservation | Autotransplantation, number of patients | Most frequent diagnoses for autotransplantation | Cryopreservation, number of patients (< 18 years) | Most frequent diagnoses for cryopreservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jadoul et al., 2017 | 545 | Lymphoma (n = 127), benign/ borderline ovarian tumour | (21)1 |

|

|

|

| Tanbo et al., 2015 | 164 | Breast cancer (n = | 2 | Lymphoma (n = 2) |

|

|

| Jadoul et al., 2010 |

|

|

|

| 58 | Sarcoma (n = 14), leukaemia (n = 14), lymphoma (n = 12) |

| Poirot et al., 2019 (18) |

|

|

|

| 418 | Neuroblastoma (n = 93), benign haematological disorders (n = |

| Lotz et al., 2020 (19) |

|

|

|

| 102 | Lymphoma (n = 34), leukaemia (n = 20), sarcoma (n = 17) |

| Kristensen et al., 2021 | 944 | Breast cancer (n = | 104 | Breast cancer (n = | 242 | Sarcoma (n = 52), leukaemia (n = 46), lymphoma (n = 38) |

| Gracia et al., 2012 | 21 | Leukaemia (n = | (13)1 |

|

|

|

| Lotz et al., 2016 (22) | 147 | Lymphoma (n = |

|

|

|

|

| Oktay et al., 2010 (23) | 59 | Lymphoma (n = | 3 | Breast cancer (n = 1), lymphoma (n = 1), |

|

|

| Hoekman | 69 | Breast cancer (n = | 7 | Breast cancer (n = |

|

|

| Dittrich et al., 2015 (3) |

|

| 20 | Lymphoma (n = |

|

|

| Shapira et al., 2020 |

|

| 60 | Lymphoma (n = 34), benign disorders (n |

|

|

1Number given in parentheses is not included in the present study due to risk of data duplication or absence of a specific diagnosis.

Due to inclusion in some of the articles of patients of all ages with no reporting of specific diagnoses for the different age groups, there is an overlap of around 90 patients between the present study's distribution of patients in the categories 'patients 0–44 years' (n = 1 947) and 'patients aged less than 18 years' (n = 820).

Results

Indications for cryopreservation

The results for cryopreservation in the age group 0–44 years are shown in Table 2, left-hand column (12, 15, 20)(20–24). Together the studies show diagnoses for a total of 1 947 patients in the age range from six months (12) to 44 years (23). Of the individual diagnoses reported, breast cancer was the most frequent indication for cryopreservation of ovarian tissue (694 of 1 947, 36 %), followed by lymphoma (416 of 1 947, 21 %). In Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands and the United States, breast cancer was the most common indication (15, 20, 21, 23, 24), while lymphoma was the most common in Belgium and Germany (12, 22). In total, malignant diseases constituted 86 % of the indications, and benign disorders 13 %. The remaining diagnoses were other, unclassified indications.

Table 2

Indications used for cryopreservation of ovarian tissue in patients aged 0–44 years and patients aged less than 18 years, as well as indications used for autotransplantation of ovarian tissue. A small group of patients may appear both in the columns 0–44 years and < 18 years. The figures are from studies published from 2010. Number (percentage of total).

| Indications used |

| Cryropreservation |

| Autotransplantation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Patients 0–44 years | Patients < 18 years |

|

| ||

| Breast cancer |

| 694 (36) |

|

| 53 (27) | |

| Lymphomas |

| 416 (21) | 94 (12) |

| 74 (38) | |

|

| Hodgkin lymphoma |

| 61 (3) |

|

| 37 (19) |

|

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

| 16 (1) |

|

| 14 (7) |

|

| Unclassified lymphomas |

| 339 (17) | 94 (12) |

| 23 (12) |

| Haematological malignancies |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| Leukaemia, myelodysplastic syndromes |

| 112 (6) | 156 (19) |

| 10 (5) |

|

| Other |

|

| 11 (1) |

|

|

| Sarcomas |

| 149 (8) | 125 (15) |

| 11 (6) | |

| Malignant gynaecological diseases |

| 154 (8) | 3 (0,4) |

| 17 (9) | |

| Malignant neurological diseases |

| 62 (3) | 166 (20) |

| 3 (2) | |

|

| Neuroblastoma |

| 1 (0) | 104 (13) |

|

|

|

| Cancer of the central nervous system |

| 61 (3) | 62 (7) |

|

|

| Malignant gastrointestinal diseases |

| 53 (3) |

|

| 7 (4) | |

| Other |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| Wilms' tumour |

|

| 19 (2) |

|

|

|

| Benign haematological disorders |

| 39 (2) | 124 (15) |

| 6 (3) |

|

| Benign gynaecological disorders, borderline ovarian tumour |

| 101 (5) | 32 (4) |

|

|

|

| Genetic diseases |

| 25 (1) | 5 (0,6) |

| 4 (2) |

|

| Systemic disease |

| 55 (3) | 47 (6) |

| 11 (6) |

|

| Other benign disorders |

| 35 (2) | 38 (5) |

|

|

|

| Other malignant diseases |

| 10 (1) |

|

|

|

|

| Other, unclassified |

| 42 (2) |

|

|

|

| Total |

| 1 947 | 820 |

| 196 | |

The second column in Table 2 shows the most frequent indications for cryopreservation of ovarian tissue in patients aged less than 18 years with diagnoses from a total of 820 patients (17–20). The most frequent indications were haematological malignancies (261 of 820, 32 %), primarily leukaemia (156 of 820, 19 %), malignant neurological diseases (166 of 820, 20 %), sarcomas (125 of 820, 15 %) and benign haematological disorders (124 of 820, 15 %). Malignant diseases constituted altogether 74 % and benign disorders 26 % of the total diagnoses in this age group.

Indications for autotransplantation

The results from the included studies are shown in Table 2 (3, 15, 20, 23)(23–25). These reported a total of 196 patients who had undergone autotransplantation of ovarian tissue. Among these, lymphoma was the most frequent indication (74 of 196, 38 %), followed by breast cancer (53 of 196, 27 %). This distribution was most pronounced in the studies from Belgium, the United States, Israel and Germany (3, 25). In the study from Denmark, breast cancer was the most frequent indication (20) (Table 1).

Discussion

This literature review shows that until now, breast cancer and lymphoma have been the most frequent indications for cryopreservation and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue. This can be explained by the fact that these cancer diagnoses are globally among the most common in patients aged less than 40 years (26), and that the risk of autotransplantation of malignant cells in relation to these diagnoses is considered to be minimal (27). For patients aged less than 20 years, leukaemia, cancer of the central nervous system and lymphoma are among the most frequent cancer diagnoses worldwide (26), which may further explain why these diagnoses are frequent indications for cryopreservation in this age group. In addition, the proportion of benign disorders was highest in patients aged less than 18 years (indication in one of four patients).

Consensus and evidence

The literature review shows that the distribution of the various diagnoses with a view to cryopreservation and autotransplantation varies between different countries, which seems to indicate a lack of consensus regarding which patients should be offered the treatment. This is primarily due to insufficient evidence as to which patients will derive the most benefit from it. It remains unclear how many patients develop premature ovarian insufficiency following gonadotoxic treatment, and who will benefit most from frozen ovarian tissue. The offer of fertility-preserving treatment is dependent on an individual assessment of each patient's disease, reproductive background and personal wishes, which may vary from one country to another as well as between centres. In Denmark, ovarian tissue is transplanted autologously into women to improve a diminished ovarian reserve, without the woman necessarily having experienced premature ovarian insufficiency. Moreover, autotransplantation is also performed to re-establish the ovaries' natural hormone production (10). This is, however, a resource-intensive alternative to regular hormone replacement therapy.

A Norwegian original article published by Johansen et al. in 2018 reported that 20 of 74 patients (27 %) developed premature ovarian insufficiency in connection with cancer therapy following cryopreservation of ovarian tissue (16). It is difficult to predict exactly which patients will develop premature ovarian insufficiency after gonadotoxic treatment. A Danish study showed that 72 % of the women who attempted to become pregnant after cancer therapy and cryopreservation of ovarian tissue were successful (28). This may partly explain why the usage rate, i.e. the number of patients who receive ovarian tissue transplantation, is relatively low – around 5 % (4, 15, 25) – despite the large quantity of ovarian tissue that is frozen. Long-term studies are needed to clarify the risk of premature ovarian insufficiency and the usage rates in these patients.

Contraindications

A number of studies have analysed the risk of autotransplantation of malignant cells that are potentially present in frozen ovarian tissue, and the risk of recurrence of the primary tumour (27). Good results are reported following treatment for breast cancer, lymphoma and sarcomas, where the risk of recurrence following autotransplantation is considered minimal (27).

Autotransplantation of ovarian tissue from patients with acute leukaemia or ovarian cancer is, however, described as high-risk (29–31). Twelve women with leukaemia have received autotransplantation of ovarian tissue globally with no recurrence of the disease (20), (32–36). Individual fragments of ovarian tissue can be examined for cancerous cells before autotransplantation, but there is no guarantee that the fragments to be transplanted are cancer-free, as at the present time this cannot be tested with available assays. Among the 360 autotransplantations worldwide, one case of recurrence of granulosa cell tumour associated with autotransplantation of ovarian tissue has been reported (31). However, ovarian cancer is a rare indication for cryopreservation, as clinicians are hesitant to perform autotransplantation for this diagnosis (27).

Radiotherapy may affect the blood supply in the pelvic region and lead to an atrophic endometrium and reduced function of the uterine muscle, which in turn can complicate a potential pregnancy (37). The outcome of autotransplantation of ovarian tissue in patients who have undergone radiotherapy directed to the pelvic region is therefore uncertain, and in some cases the procedure is contraindicated (37). Shapira et al. reported that a patient treated for colorectal cancer with radiation doses up to 45 Gy gave birth prematurely, whereas patients who received total body irradiation with doses less than 20 Gy gave birth at term without complications. No patients with cervical cancer became pregnant (25). Dittritch et al. showed similar results for patients treated for anal cancer (3). Here the patients received a radiation dose of 50 Gy, which corresponds to an organ dose of more than 30 Gy directed to the uterus. Among four women with anal cancer, none became pregnant after autotransplantation, despite regular menstruation (3).

Weaknesses

A large proportion of articles were excluded due to absence of specific diagnoses or risk of data duplication, and therefore our study does not provide a complete overview of patients treated with cryopreservation and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue as described in the literature. Beyond this, it has not been possible to describe the indications with absolute precision, as the included articles do not use the same diagnostic distribution. A small proportion of patients appear in both the categories 'patients aged 0–44 years' and 'patients aged less than 18 years', as it is difficult to avoid data duplication, but the distribution nevertheless provides an impression of the differences between the two age groups.

Conclusion

This literature review shows that breast cancer and lymphoma have been the most frequent indications for cryopreservation and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue. Long-term experience and more outcomes from patients who have received autotransplantation of ovarian tissue will hopefully result in even better guidelines regarding which patients derive the greatest benefit from the treatment, and more consensus in this field.

The authors would like to thank Professor Emeritus Tom Tanbo at the Department of Reproductive Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, for information about cryopreservation and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue in Norway. The article has been peer-reviewed.

Main findings

Breast cancer and lymphoma were the most frequent indications for cryopreservation and autotransplantation of ovarian tissue.

Leukaemia, malignant neurological diseases, sarcomas and benign haematological disorders were the most common indications for cryopreservation of ovarian tissue in patients aged less than 18 years.

In patients less than 18 years of age, 26 % of the indications were benign disorders. The indications varied between different countries and centres.

- 1.

Veileder i gynekologi: Prematur ovarialinsuffisiens. Oslo: Norsk Gynekologisk forening, 2021. https://www.legeforeningen.no/foreningsledd/fagmed/norsk-gynekologisk-forening/veiledere/veileder-i-gynekologi/ Accessed 6.3.2021.

- 2.

Gellert SE, Pors SE, Kristensen SG et al. Transplantation of frozen-thawed ovarian tissue: an update on worldwide activity published in peer-reviewed papers and on the Danish cohort. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018; 35: 561–70. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Dittrich R, Hackl J, Lotz L et al. Pregnancies and live births after 20 transplantations of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a single center. Fertil Steril 2015; 103: 462–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Rosendahl M, Schmidt KT, Ernst E et al. Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue for a decade in Denmark: a view of the technique. Reprod Biomed Online 2011; 22: 162–71. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Stensvold E, Magelssen H, Oskam IC. Fertilitetsbevarende tiltak hos jenter og unge kvinner med kreft. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2011; 131: 1429–32. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

Dansk Fertilitetsselskab. Fertilitetsbevaring ved malign sygdom. https://fertilitetsselskab.dk/kliniske-guidelines-i-brug/ Accessed 10.3.2021.

- 7.

Dolmans MM, Donnez J. Fertility preservation in women for medical and social reasons: Oocytes vs ovarian tissue. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2021; 70: 63–80. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Storeng R, Abyholm T, Tanbo T. Kryopreservering av ovarialvev. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2007; 127: 1045–8. [PubMed]

- 9.

Wallace WH, Smith AG, Kelsey TW et al. Fertility preservation for girls and young women with cancer: population-based validation of criteria for ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1129–36. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Jensen AK, Kristensen SG, Macklon KT et al. Outcomes of transplantations of cryopreserved ovarian tissue to 41 women in Denmark. Hum Reprod 2015; 30: 2838–45. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Pacheco F, Oktay K. Current success and efficiency of autologous ovarian transplantation: A meta-analysis. Reprod Sci 2017; 24: 1111–20. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Jadoul P, Guilmain A, Squifflet J et al. Efficacy of ovarian tissue cryopreservation for fertility preservation: lessons learned from 545 cases. Hum Reprod 2017; 32: 1046–54. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Fertility preservation in women. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1657–65. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Tanbo T, Tinkanen H et al. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation among alternatives for fertility preservation in the Nordic countries - compilation of 20 years of multicenter experience. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016; 95: 1015–26. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Tanbo T, Greggains G, Storeng R et al. Autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue after treatment for malignant disease - the first Norwegian results. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015; 94: 937–41. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Johansen MS, Tanbo TG, Oldereid NB. Fertilitet etter kryopreservering av ovarialvev ved kreftbehandling. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2018; 138. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.17.0719. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 17.

Jadoul P, Dolmans MM, Donnez J. Fertility preservation in girls during childhood: is it feasible, efficient and safe and to whom should it be proposed? Hum Reprod Update 2010; 16: 617–30. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 18.

Poirot C, Brugieres L, Yakouben K et al. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation for fertility preservation in 418 girls and adolescents up to 15 years of age facing highly gonadotoxic treatment. Twenty years of experience at a single center. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2019; 98: 630–7. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 19.

Lotz L, Barbosa PR, Knorr C et al. The safety and satisfaction of ovarian tissue cryopreservation in prepubertal and adolescent girls. Reprod Biomed Online 2020; 40: 547–54. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Kristensen SG, Wakimoto Y, Colmorn LB et al. Use of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in the Danish fertility preservation cohort. Fertil Steril 2021; 116: 1098–106. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 21.

Gracia CR, Chang J, Kondapalli L et al. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation for fertility preservation in cancer patients: successful establishment and feasibility of a multidisciplinary collaboration. J Assist Reprod Genet 2012; 29: 495–502. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 22.

Lotz L, Maktabi A, Hoffmann I et al. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation and retransplantation–what do patients think about it? Reprod Biomed Online 2016; 32: 394–400. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Oktay K, Oktem O. Ovarian cryopreservation and transplantation for fertility preservation for medical indications: report of an ongoing experience. Fertil Steril 2010; 93: 762–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 24.

Hoekman EJ, Louwe LA, Rooijers M et al. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation: Low usage rates and high live-birth rate after transplantation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020; 99: 213–21. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 25.

Shapira M, Dolmans MM, Silber S et al. Evaluation of ovarian tissue transplantation: results from three clinical centers. Fertil Steril 2020; 114: 388–97. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 26.

World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer today. https://gco.iarc.fr/ Accessed 20.5.2021.

- 27.

Dolmans MM, Masciangelo R. Risk of transplanting malignant cells in cryopreserved ovarian tissue. Minerva Ginecol 2018; 70: 436–43. [PubMed]

- 28.

Schmidt KT, Nyboe Andersen A, Greve T et al. Fertility in cancer patients after cryopreservation of one ovary. Reprod Biomed Online 2013; 26: 272–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 29.

Dolmans MM, Marinescu C, Saussoy P et al. Reimplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue from patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia is potentially unsafe. Blood 2010; 116: 2908–14. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 30.

Rosendahl M, Andersen MT, Ralfkiær E et al. Evidence of residual disease in cryopreserved ovarian cortex from female patients with leukemia. Fertil Steril 2010; 94: 2186–90. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 31.

Stern CJ, Gook D, Hale LG et al. Delivery of twins following heterotopic grafting of frozen-thawed ovarian tissue. Hum Reprod 2014; 29: 1828. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 32.

Meirow D, Ra'anani H, Shapira M et al. Transplantations of frozen-thawed ovarian tissue demonstrate high reproductive performance and the need to revise restrictive criteria. Fertil Steril 2016; 106: 467–74. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 33.

Shapira M, Raanani H, Barshack I et al. First delivery in a leukemia survivor after transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue, evaluated for leukemia cells contamination. Fertil Steril 2018; 109: 48–53. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 34.

Silber SJ, DeRosa M, Goldsmith S et al. Cryopreservation and transplantation of ovarian tissue: results from one center in the USA. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018; 35: 2205–13. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 35.

Sonmezer M, Ozkavukcu S, Sukur YE et al. First pregnancy and live birth in Turkey following frozen-thawed ovarian tissue transplantation in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who underwent cord blood transplantation. J Assist Reprod Genet 2020; 37: 2033–43. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 36.

Poirot C, Fortin A, Dhédin N et al. Post-transplant outcome of ovarian tissue cryopreserved after chemotherapy in hematologic malignancies. Haematologica 2019; 104: e360–3. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 37.

Teh WT, Stern C, Chander S et al. The impact of uterine radiation on subsequent fertility and pregnancy outcomes. BioMed Res Int 2014; 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/482968. [PubMed][CrossRef]