Main findings

In 2018, three prescriptions were rediscovered in Henrik Ibsen's wallet. Two had been issued by his doctor, Edvard Bull, in 1903.

The prescriptions show that he used potassium iodide, potassium bromide and uricedin, likely for arteriosclerosis, insomnia and constipation.

Ibsen's medical treatment was in line with medical science at the time.

Henrik Ibsen's daughter-in-law, Bergliot Ibsen (1869–1953), bequeathed a number of his personal possessions to the Ibsen Society (1). The plan was to transform Venstøp farm, Ibsen's childhood home, into a museum, with his possessions forming its core collection (2, 3). One of the items was a wallet containing three prescriptions. We have previously written about Ibsen's health (4), his doctors (5) and the medication orders he wrote (6), but back in 2006, we were unaware of the prescriptions. What medications are involved, what was the treatment for and could it have been harmful to him?

Material and method

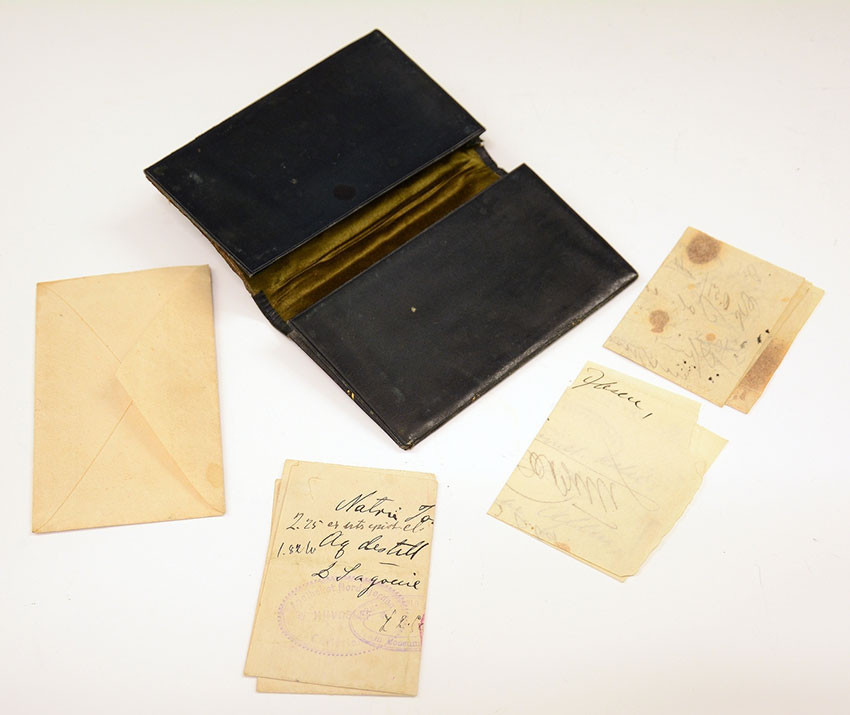

The Henrik Ibsen Museum has published eleven images of the wallet and its contents on the Digital Museum website (Figure 1) (1). The prescriptions were found during the cataloguing of items in 1953, as noted in the cataloguing protocols, but they were put back in their place without being shared or analysed. The wallet measures 12 × 7.9 cm and is made of green leather, with two compartments and moss green lining. The exterior is adorned with gold-trimmed edges (1).

We used available information about Henrik's (1828–1906) and his wife Suzannah Ibsen's (1836–1914) health, and linked this to the medical literature of the time, especially textbooks and handbooks. The first edition of the pharmacology textbook from 1905 was a particularly important source (7).

The prescriptions

The wallet, which may have actually been a folder for storing prescriptions, contains three prescriptions, one of which was issued in Italy, and an envelope. Two of the prescriptions were written by Ibsen's doctor, Edvard Bull (1845–1925). We present these first.

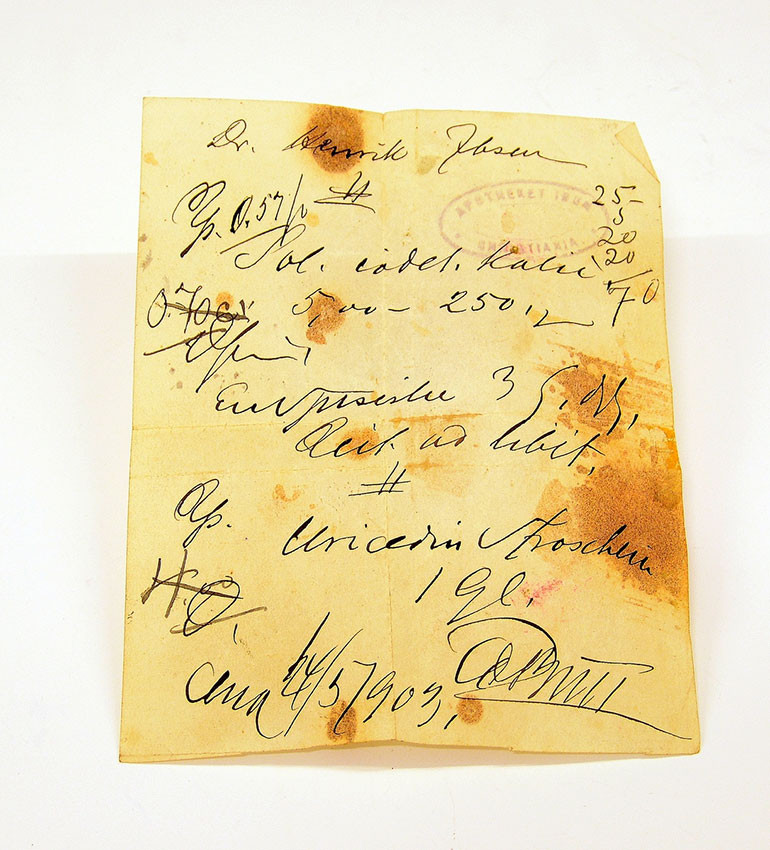

Prescription 1 (Figure 2)

Bull's handwriting is distinctive and relatively easy to read:

Dr. Henrik Ibsen

#

Sol. iodet. kalii

5,00 - 250

En Spiseske 3 G. dgl. [One tablespoon 3 times daily]

Reit. ad libit. [Rep. ad libit.]

#

Uricedin Stroschein

1 Gl.

Chra 24/5 1903 Edv. Bull

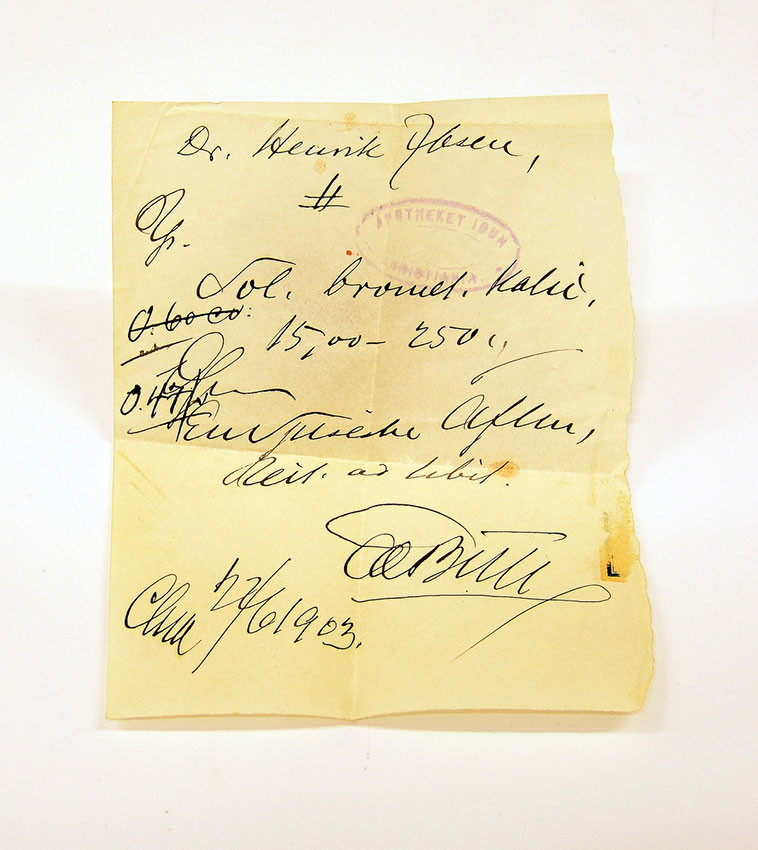

Prescription 2 (Figure 3)

This prescription was written just under a month after the first one:

Dr. Henrik Ibsen

#

Sol. bromet. kalii

15,00 - 250

En Spiseske Aften [One tablespoon evening]

Reit. ad libit. [Rep. Ad libit.]

Chra 22/6 1903 Edv. Bull

Analysis

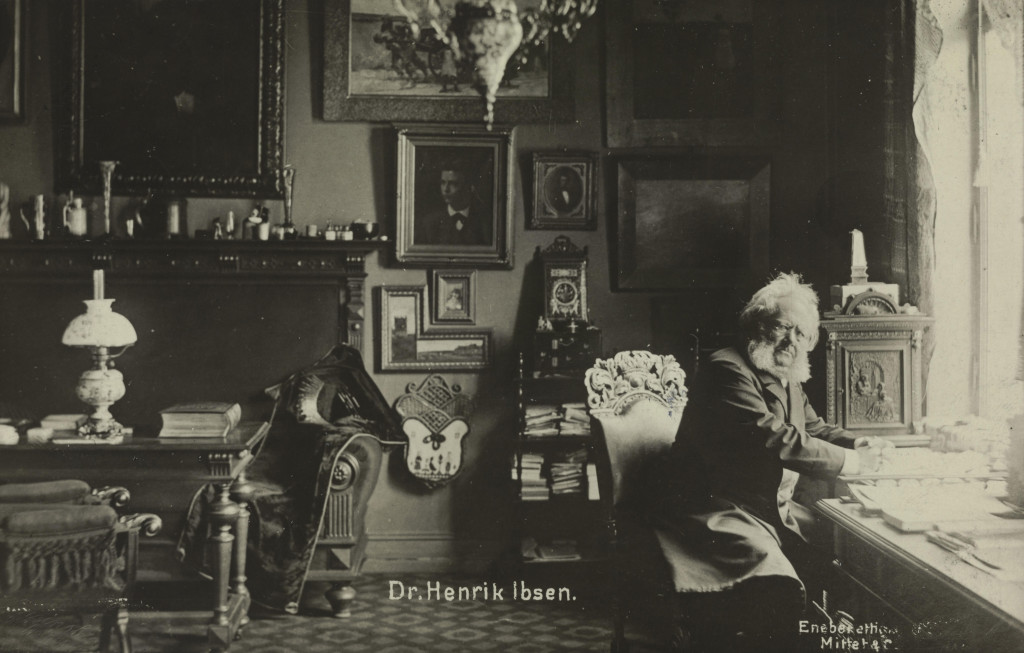

Both prescriptions are stamped 'Apotheket Idun Christiania', which was the name of Ibsen's nearest pharmacy. It opened in 1887 and was located at Løkkeveien 11 in Kristiania (now Oslo), at the end of Arbiens gate (now Arbins gate) (6). Ibsen probably did not collect the prescriptions himself, as by 1903 he would not have been strong enough for that. As Bull put it: 'He was a man broken by illness'. He could 'walk a little with the help of a cane', had trouble speaking, his memory and intelligence were impaired, and his mood was 'extremely irritable' (4).

The first prescription is dated 24 May 1903, the very day that Edvard Bull became Ibsen's doctor. This was a Sunday, which aligns with the written account from Bull's son, Francis Bull (1887–1974), describing how his father 'visited his famous patient every day, Sunday included' (8). The son's account also suggests that there was urgency in securing a new doctor, as problems had arisen with the previous one. According to Bergliot Ibsen, she was the one who arranged it: 'After that, I walked up to Dr Edvard Bull, who came immediately' (5).

Bull qualified as a doctor in 1870, making him the eighth doctor in Norway, and obtained his doctorate five years later. He worked for several years at Norway's national hospital (Rikshospitalet) before becoming a family doctor in Norway's capital city, where he built an extensive practice. Over time, his practice became dominated by patients from Kristiania's upper class and its artistic community (5).

One of the medications on the prescription was Sol. iodet. kalii (solutio iodeti kalii), which is a solution of potassium iodide (iodetum kalicum). The Norwegian term used for this in Ibsen's day was jodkalium (6). The other medication was uricedin.

The active ingredients

Potassium iodide

Ibsen's own orders for medication, which we described in the 2006 article, included sodium iodide (6). It was used for syphilis, arteriosclerosis, tuberculosis and several other conditions (7, pp. 416–7). Edvard Bull's prescription is for potassium iodide. At the time, these substances were considered to have approximately the same effect (7, p. 415). In 2006, we did not know why Ibsen used one rather than the other. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832–1910) claimed that Ibsen used potassium iodide, and that it was Bull who 'performed a miracle' and treated him with this remedy, which 'in France has been found to treat calcification' (9). And it seems that Bjørnson was right. Bull prescribed potassium iodide when he became Ibsen's doctor in May 1903.

But why did Ibsen order sodium iodide a few years earlier (6)? We cannot know for sure, but it must be considered in light of the Italian prescription that was written for Ibsen's wife, which we discuss towards the end of this article.

It is also unclear why Bjørnson was so enthusiastic about the effects of potassium iodide. There is no reason to believe that the active substance accomplished 'a miracle'. It is doubtful that it had any clinical effect at all, so Bjørnson's enthusiasm may perhaps reflect a more general sense that Ibsen was finally receiving 'more attentive medical assistance', as Bull himself wrote (5).

The pharmacology textbook describes the two iodine preparations as quite similar (7, p. 413). Potassium iodide was a well-established remedy that had been in use since the 1820s and 'was widely used in medicine', according to documentation from 1896 (10, p. 67). Potassium iodide was the most commonly used form of iodine for internal use, as it typically did not irritate the mucous membranes or otherwise harm digestion (11, p. 331). Sodium iodide was newer, dating back to the 1890s (6).

It was not uncommon to write 'Rep. ad libit.' (repeat ad libitum) on prescriptions, allowing Ibsen to continue this medication as long as he wished ('as desired') rather than the doctor having to renew his prescriptions. Bull likely anticipated that Ibsen would be using these medications for a long time to come. This was a practical solution and undoubtedly reflected Bull's trust in Ibsen. Perhaps that is why there was no need for further prescriptions? In any case, these were the only two prescriptions from Bull that were found in 1953.

The pharmacy worked out the cost of the potassium iodide solution, as seen by the calculation at the top right. It includes the active ingredient, packaging, preparation costs, etc. Calculations like this were common when making medications according to prescriptions (Inger Lise Eriksen, personal communication).

One tablespoon of the potassium iodide solution was to be taken three times a day (7, p. 418). A tablespoon was approximately 15 grams (7, p. 538). '5,00–250' indicates that 5 grams of the medication was to be weighed and added to water until the total weight reached 250 grams (7, p. 558).

Uricedin

The second preparation on the prescription from 24 May 1903 is uricedin, which was a mixture of sodium sulphate, sulphate chloride and sulphate citrate, as well as lithium citrate (12, 13). It was a relatively new remedy, registered in Germany in 1894 (14), and was produced by the company J.E. Stroschein in Berlin, which Bull specified on the prescription. Counterfeit versions circulated on the market, so doctors were encouraged to indicate the manufacturer's name.

In 1895, The Lancet reported positive effects for the treatment of gout. Hugo Langstein, a doctor at a spa resort in Teplitz-Schönau, claimed to have achieved good results after testing it on himself first (15). Ten years later, the range of indications had expanded significantly (16), but the common denominator was uric acid diathesis, leaving patients predisposed to illnesses such as kidney stones and gout due to acidic urine (17). The remedy was available in Norway and was listed in the Index medicamentorum as late as 1945 (18).

However, it seems that the remedy soon fell into disrepute. As early as 1904, it was said that uricedin had no specific effect, 'but is expensive' (19). A British professor reported a laxative effect, but despite its pleasant purgative action in chronic gout, he believed that the remedy would likely be poorly received due to exaggerated claims about its benefits (16). In JAMA in 1907, it was concluded that it was snake oil, and the remedy was labelled a nostrum (20) – a type of medicine that was ineffective or untested, and marketed with dubious or exaggerated claims. In Norway, such remedies were referred to as arcane (6).

If it was indeed gout that was the indication, it is conceivable that Suzannah was the recipient. She had been suffering for many years, and by around 1900, she was so weak from gout that she struggled to walk (21). However, it is unlikely that Bull would have added a medication for Suzannah to her husband's prescription.

Bull only provided the briefest of instructions about how the remedy should be used: one glass, while potassium iodide was to be taken three times daily. It was also not repeated ad libitum. The main ingredient was sodium sulphate or Glauber's salt (20), which was a laxative (7, p. 354). With Ibsen's decreasing activity after his strokes, it is quite likely that this treatment was indicated. Ibsen was already familiar with laxatives, such as the stomach remedy Brandt's Swiss pills (6).

Bull himself believed in the therapy, as he wrote: 'the initiated treatment began to have a favourable effect on his condition' and 'During treatment, his condition gradually improved' (4).

Potassium bromide

The second prescription is dated 22 June 1903, less than a month after the first. It concerns only one medication: Sol. bromet. kalii (solutio brometi kalii), which is a solution of potassium bromide (brometum kalicum).

Potassium bromide had been in use as a sedative and soporific remedy since the mid-19th century, and was widely used until the early 20th century when it was replaced by medications with fewer side effects. This is consistent with Bergliot Ibsen's account that Dr Bull 'immediately came and comforted my poor mother-in-law and gave Ibsen a sedative so he could rest and sleep. Before Dr Bull was his doctor, Ibsen would endlessly wander from one room to another during the night. Now he was able to sleep' (5).

Potassium bromide had two main indications: as a sedative and antispasmodic, and as a hypnotic. The combination of calming and sleep-inducing effects may have been beneficial in Ibsen's case. The sleep was restful and free from the typical aftereffects commonly associated with most other hypnotics (22, pp. 88–91).

Bull prescribed a tablespoon of potassium bromide in the evening, which had the desired effect. He wrote that sleep was 'splendid'. Ibsen went to bed early, fell asleep immediately, and slept all night without moving until well into the morning (23).

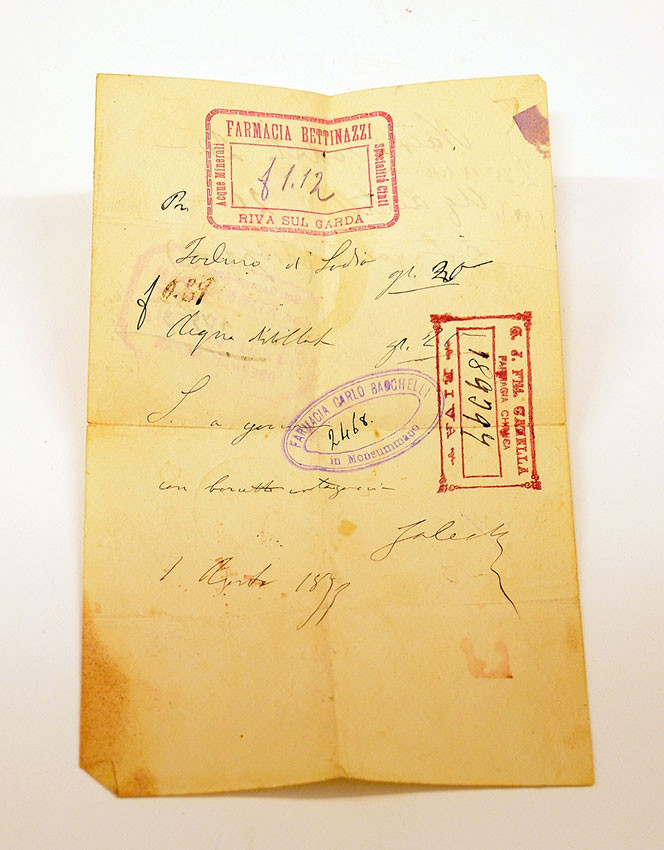

The Italian prescription

In the prescription folder, there are two documents with Italian text. One is an empty envelope from a pharmacy (farmacia chimica) called Canella, which indicates that the establishment operated in the field of mineral water, carbonated drinks and seltzer (acque minerali, gasose e seldtz). They had their own specialties, both Italian and foreign (specialita proprie, nazionali ed estere), and produced acqua di cedro (lemon liqueur). At the very bottom of the envelope is the name 'Riva', which is probably the location of the pharmacy, likely to be Riva del Garda, a port town at the northwestern end of Lake Garda in Italy. Due to the mild climate, the area was used as a spa resort, and Suzannah had visited there previously (24, p. 92).

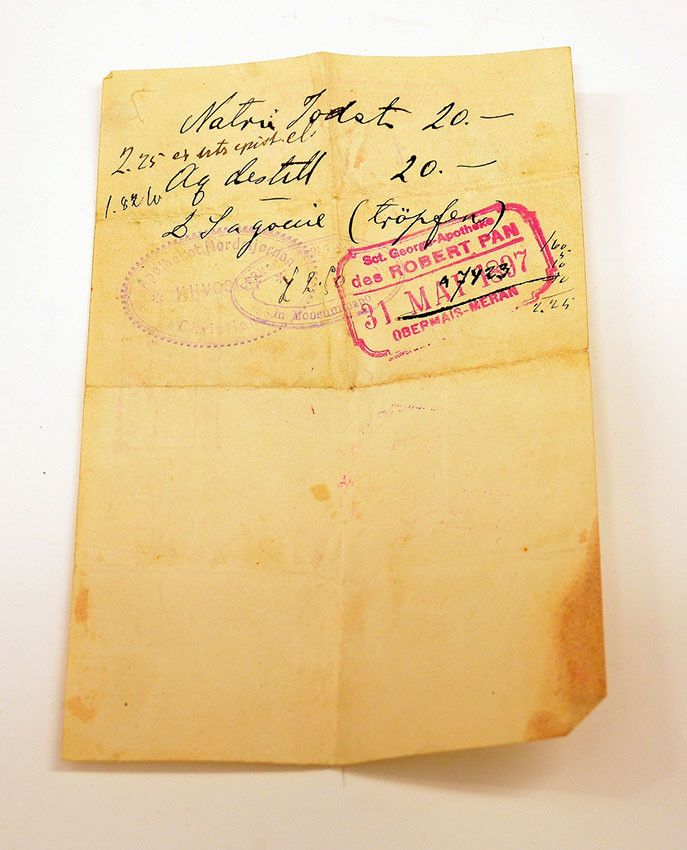

The second document is a prescription that is more difficult to interpret than the Norwegian ones. On the front, it states that sodium iodide should be mixed with aqua destillata (distilled water) and taken as drops (Figure 4):

Natr. Iodet. 20 –

Aq destill 20 –

S a gocie (tröpfen)

The prescription was collected three times: twice in Italy and once in Norway. The first stamp is dated 31 May 1897, at Sct. George-Apotheke des Robert Pan in Obermais, a district in Meran, South Tyrol. This aligns with what we know about the travel route of Suzannah and her son Sigurd on their way to a spa resort in Italy in 1897: they took the train to Copenhagen on 1 May, then continued on 8 May to Berlin and Munich, and from there to Meran and Monsummano (24, p. 398).

They stayed in Meran from 18 May to 22 June (24, p. 398) at the Schloss Labers Hotel, where they had resided previously. Ibsen himself was at home in Norway. He did not travel abroad after 1891, except for trips to Copenhagen and Stockholm for his 70th birthday celebrations in 1898 (Erik Edvardsen, personal communication). There can be no doubt, therefore, that this is Suzannah's prescription. We do not know why she used sodium iodide – gout was not a common indication for it.

The destination in 1897 was the spa resort at Monsummano, located between Florence and Lucca. In 1849, a cave named Grotta Giusti was discovered. It was 248 metres long and 12 metres wide, and was naturally divided into four chambers with varying temperatures. The baths were particularly popular among gout and rheumatism sufferers (24, p. 343). A stay there was referred to as a 'cave treatment'. The second stamp is from a pharmacy in Monsummano, called Farmacia Carlo Baccelli.

Ibsen enquired about Suzannah in a letter to Sigurd on 17 June: 'I am very eager to know how she is faring in Monsummano. Is the air good for her, and has she started the treatment yet?' (25) A couple of weeks later, he wrote: 'The main thing, of course, is how the cave treatment is benefitting you this year' (26). This was the golden age of spa treatments. According to the pharmacologist Poulsson, the benefits of spa trips were completely understandable due to several factors: the favourable climate, a structured routine, physical activity, time spent outdoors, a suitable diet, relief from the burdens of everyday life, suggestion, and the expertise of the spa doctors (7, p. 349).

In the letter dated 2 July, Ibsen explicitly wrote about the medication: 'The iodine tincture, which upset you in Labers, you should of course discard and get a new bottle down there.' This comment has led Ibsen scholars to believe that iodine tincture was a solution of iodine in alcohol, used to disinfect the skin (24, p. 411), but this is a misunderstanding. We can see from the prescription that the medication was given as drops for internal use.

In addition to unpleasant side effects after prolonged use, including iodism, it was also known to cause idiosyncratic reactions such as hypersensitivity within just a few hours of taking the first doses (7, pp. 414–5). A larger dose of iodine or iodine tincture could induce gastroenteritis due to the preparation's 'caustically irritating effect' on the ventricle and intestines (22, p. 96). It is possible that these were the issues Suzannah encountered.

The prescription bears stamps from two Italian pharmacies in Meran and Monsummano from the summer of 1897. Suzannah must have felt unwell from the treatment in Meran and evidently followed Henrik's advice to get a new bottle in Monsummano. There is also a third stamp from Apotheket Nordstjernen, located at Stortingsgata 6, which was established in 1866 by Hans Henrik Hvoslef (1831–1911). This was the Norwegian capital's seventh pharmacy, and we can see Hvoslef's name in the centre of the stamp (27). It is not clear when Sigurd and Suzannah returned from their spa trip to Italy, but the medication clearly continued even after she was back home, and the pharmacy must have accepted the Italian prescription. Curiously, the prescription is neither dated nor signed. Poulsson wrote that the patient's name can be omitted if the medication reveals an illness that the patient wishes to keep private (7, p. 534). This is probably not relevant here, as the prescription lacks most of the formalities: time, place, and the names of the patient and doctor. However, it was clearly intended to be understood in both Italian and German, as the word 'drops' is written in both languages (goccia and tröpfen). Some details are also given on the back of the prescription (Figure 5):

Iodino et Sodia [unclear specification] 20

Aqua distillat. [unclear specification] 20

S. a goucie [for drops]

con boccetta contagocce [with dropper bottle]

Jalech ... [illegible]

1. Agusto 1897 [?] [1 August 1897?]

It is not known why sodium iodide had to be prescribed again – the handwriting on the back is different from the front. The back is also stamped three times, but none of the stamps have a date. We interpret the handwritten date as 1 August 1897, so this must be the second side of the page, as the other side had a stamp from May 1897.

One of the stamps is from the pharmacy Farmacia Chimica Canelli, the same establishment that made the envelope in the prescription folder, and which may have been located near Riva del Garda. Perhaps this is where Suzannah and Sigurd obtained the prescription folder. The second stamp is also from there, Farmacia Bettinazzi. The last stamp is from Monsummano, where they collected the medication at Farmacia Carlo Bacchelli.

The prescription where both sides of the page are used has been stamped at five different pharmacies: one in Meran, two in Riva, one in Monsummano (collected twice) and one in Kristiania. If all of this took place in 1897, as it appears, it would follow that Suzannah could continue using this prescription once she returned to Norway. Perhaps it was something like this that led Dr Ibsen to take matters into his own hands in 1898 and start writing orders for medication for his gout-ridden wife (6)?

The Italian prescription from August 1897 is very precise: Solutio a goucie con boccetta contagocce, meaning the medication is to be taken as drops from a dropper bottle. Ibsen wrote the same on his order for medication: 'NB! In dropper bottle with pipette' (6). The small quantities that were likely being referred to were easily and accurately measured by counting the drops from a dropper bottle or using a pipette. However, we do not know why Ibsen ordered this himself. At the time, Christian Sontum (1858–1902) was the Ibsens' family doctor (5). They had an excellent relationship, and we would have thought Sontum would be the most likely person to write the family's prescriptions.

Between the first and second lines on the front side of the prescription, we believe it says 'ex vitr epist el', which could stand for ex vitreus epistomium elongatum, meaning a glass/bottle with an extended stopper, where ex vitreus indicates that the stopper is made of glass, and epistomium elongatum describes the form it takes. It was common to specify the type of packaging or clarify what the price related to (Inger Lise Eriksen, personal communication).

'a man broken by illness'

The last three years of Ibsen's life were marked by illness (4), and Suzannah also had significant health issues (21). The apartment on Arbiens gate was like a nursing home, with its own nurse and daily medical supervision.

Ibsen's health was a factor in his not receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature. When the Swedish Academy's Nobel Committee concluded its discussions on 14 September 1903 on whether it was possible to share the prize between Bjørnson and Ibsen, it decided that 'a division could easily be misunderstood, as both of these writers are too distinguished to receive only half the prize. Furthermore, since it has come to our attention, through reliable and completely trustworthy sources, that Ibsen is now a man broken by illness, with his life force fading, it seems less prudent from this perspective to nominate him for the Nobel Prize (...)' (28).

Summary

The prescriptions show that Ibsen used three medications, and he likely started taking them when Edvard Bull became his doctor in 1903: potassium iodide, potassium bromide and uricedin. Suzannah also used an iodine-based medication, but in the form of sodium iodide. It is unclear whether she had used this before 1897, but she was certainly prescribed it during her trip to Italy in the summer of that year, and continued using it after returning to Norway.

Ibsen's orders for medication in the period 1898–1901 were for sodium iodide and Brandt's Swiss pills (6). We originally thought these medications were for his own use, but now that we know Suzannah used sodium iodide, it is possible that Ibsen ordered them for his wife. The advertisement for Brandt's Swiss pills also emphasised that they were 'often taken by women due to their mild effects' (29), which could suggest they were intended for Suzannah. However, we know that after Suzannah's death in 1914, it was almost exclusively Henrik's possessions that were kept (Erik Edvardsen, personal communication). Among them is a box of Brandt's Swiss pills, which could indicate that Ibsen himself used them. It is entirely conceivable that Henrik used sodium iodide, perhaps prescribed by Dr Sontum, and that Dr Bull switched this to potassium iodide. But we cannot be certain.

Was the medication harmful to Ibsen? The answer is no, probably not. The medical treatment was in accordance with the medical standards of the time, as evidenced by comparisons with contemporary literature. Moreover, Bull showed an extraordinary commitment to Ibsen's health for the last three years, attending to the poet 'more than 1000 times' (23, p. 141). Ibsen was treated by a highly competent doctor who provided him with the best possible care. Iodine treatment was not without its risks (11, p. 331), but any problems or side effects of the medication would likely have been addressed. The bromine treatment was certainly beneficial as a sedative and sleeping aid. We have to assume that Bull made full use of the placebo effect.

We would like to thank Inger Lise Eriksen, former pharmacist and chair of the Norwegian Pharmaceutical History Museum, for interpreting the prescriptions, and Erik H. Edvardsen, conservator at the Ibsen Museum & Theatre, for his input to the article.

- 1.

Digitalt museum. Telemark museum. Lommebok. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021027937176/lommebok Accessed 19.7.2024.

- 2.

Østvedt E. Ibsenforbundet formål og oppgaver. I: Østvedt E, red. Ibsen-årbok 1952. Skien: Oluf Rasmussens boktrykkeri, 1952: 5–7.

- 3.

Ibsen-effekter til Skien. Varden 17.11.1953: 1–2.

- 4.

Frich JC, Hem E. Den fatale historie – Ibsens helse i hans siste år. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2006; 126: 1497–501. [PubMed]

- 5.

Hem E, Frich JC. Ibsens siste år – legene og deres krevende pasient. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2006; 126: 1502–6. [PubMed]

- 6.

Hem E, Andersen KE. En apotekerlærling krysser sitt spor – om Ibsens medisinbestillinger. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2006; 126: 3314–7. [PubMed]

- 7.

Poulsson E. Lærebog i farmakologi for læger og studerende. Kristiania: Aschehoug, 1905.

- 8.

Bull F. Tradisjoner og minner. Oslo: Gyldendal, 1945: 189.

- 9.

Bjørnson om Henrik Ibsen. Aftenposten: Ukens nytt 26.5.1906: 4–5.

- 10.

Illustreret konversationsleksikon: en haandbog for alle. Bd. 5: Irving-Kvægpest. Kjøbenhavn: Hagerups boghandel, 1896: 67.

- 11.

Greve M. Veileder i sundhed og sygdom: en haandbog med alfabetisk ordnede artikler. Lægebog for norske hjem. Kristiania: Cammermeyer, 1904.

- 12.

Urecidin. I: Merck's 1899 Manual of the Materia Medica. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41697/41697-h/41697-h.htm Accessed 19.7.2024.

- 13.

Uricedin. I: Aulde J, red. The American Therapist: a monthly record of modern therapeutics. Bd. 2: juli 1893–1894. New York: The American Therapist Publishing Company: 48.

- 14.

Uricedin. I: Norsk Kunngjørelsestidende 21.9.1931: 3.

- 15.

Uricedin in uric acid diathesis. Lancet 1895; 145: 50.

- 16.

Tirard N. Some clinical observations with new remedies. Lancet 1905; 165: 83–4. [CrossRef]

- 17.

Johnson FN. The first era in medicine. I: Johnson FN, red. The history of lithium therapy. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1984: 5–33.

- 18.

Schmidt L, Abildgaard H. Index medicamentorum 1945: fortegnelse over lægemidler med gruppe-inndeling. Oslo: Norges Apotekerforening, 1945: 524.

- 19.

Referater og oversættelser. Den medikamentøse behandling af nyresten. Medicinsk Revue 1904; 21: 367.

- 20.

Pharmacology. JAMA 1907; XLIX: 1788–9. [CrossRef]

- 21.

Ystad V. Suzannah Daae Ibsen. https://snl.no/Suzannah_Daae_Ibsen Accessed 19.7.2024.

- 22.

Hoch F. Pharmacologisk Compendium: udarbeidet i Henhold til de Nordiske Pharmacopoeer, for Medicinere, Pharmaceuter, Læger og Apotheker-Revisorer. Del 2. Christiania: Den Norske Forlagsforening, 1880.

- 23.

Bull E. Fra Henrik Ibsens tre sidste Leveaar. Optegnelser af Dr. med. Edv. Bull Juli 1906. Ms. 4º 3159. Håndskriftsamlingen, Nasjonalbiblioteket i Oslo. Gjengitt i: Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift 1994; 2: 140–50.

- 24.

Ibsen H. Henrik Ibsens skrifter: Innledning og kommentarer. Bd. 15. Oslo: Aschehoug, 2010.

- 25.

Henrik Ibsens skrifter, Universitetet i Oslo. Brev til Sigurd Ibsen 17.6.1897 (B18950617SiI). https://www.ibsen.uio.no/BREV_1890-1905ht%7CB18950617SiI.xhtml Accessed 19.7.2024.

- 26.

Henrik Ibsens skrifter, Universitetet i Oslo. Brev til Susanna Ibsen 2.7.1897 (B18950702SuI). https://www.ibsen.uio.no/BREV_1890-1905ht%7CB18950702SuI.xhtml Accessed 19.7.2024.

- 27.

Oslo byleksikon. Apoteket Nordstjernen. https://oslobyleksikon.no/side/Apoteket_Nordstjernen Accessed 19.7.2024.

- 28.

Svensén B, red. Nobelpriset i litteratur: nomineringar och utlåtanden 1901–1950. D. 28: 1901–1920. Stockholm: Svenska Akademien, 2001: 53.

- 29.

Apotheker Rich. Brandt's Schweizerpiller (annonse). Dagbladet 15.10.1892: 2.