This case report describes airway aspiration of a foreign body in a child. The child initially presented with mild respiratory symptoms but rapidly progressed to respiratory failure and life-threatening complications.

A two-year-old child was referred to the emergency department by their general practitioner (GP) due to respiratory symptoms. The father reported that the child had been coughing for two weeks without any additional symptoms. However, two days before admission, the child's condition deteriorated, they were less active and the cough worsened. The GP suspected a viral respiratory infection and referred the child to the paediatric department at the hospital.

The duty paediatricians examined the child upon arrival. The child was alert but pale and fatigued. Breathing was laboured with intercostal and subcostal retractions. On auscultation, wheezing and crackles were heard from the lungs. The respiratory rate was 80 - 90 breaths per minute (reference range 25 - 35). Heart auscultation findings were normal, and the pulse was 180 beats per minute (90 - 130). Oxygen saturation was 74 % on room air and 95 % with 7 litres of oxygen on a mask. The child was afebrile.

The blood tests showed CRP 214 mg/L (<5), white blood cells 16.9 × 109/L (3.5–14.0 × 109/L), capillary pH 7.42 (7.35–7.45), and pCO2 4.2 kPa (4.7–5.9).

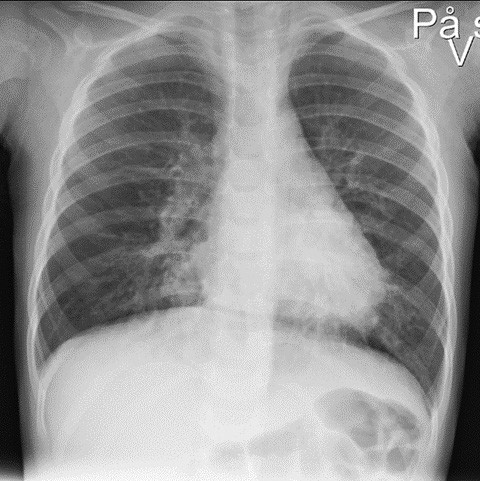

The condition was interpreted as pneumonia, and the patient was admitted to the paediatric ward. A total of 315 mg of penicillin was administered intravenously, and high-flow nasal cannula therapy was started at a rate of 15–25 litres per minute and 40 % oxygen supplementation. Inhalations with 3 ml NaCl and 2.5 mg of salbutamol had an uncertain effect. Chest X-ray showed perihilar opacities (Figure 1). After five hours, the child appeared more fatigued but was still aware of their surroundings. Breathing entailed wheezing with prolonged expiration. The duty paediatrician noted diminished breath sounds on the right side.

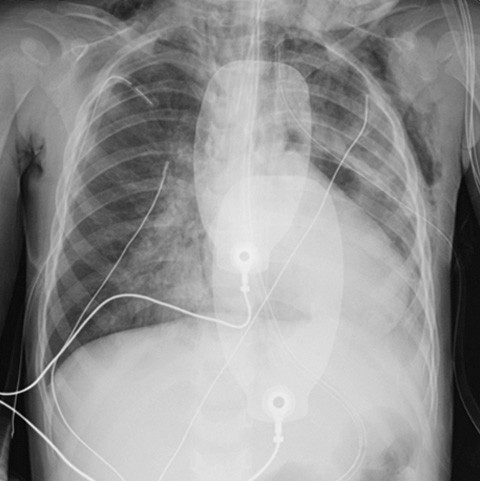

A total of 48 mg of intravenous hydrocortisone was administered, along with more frequent inhalations of NaCl and salbutamol in the same dose as before. A capillary blood gas test at this time showed a pH of 7.29 and PCO2 of 6.7 kPa. The child was transferred to the intensive care unit. Swelling in the neck was observed. A new chest X-ray showed pneumomediastinum and soft tissue emphysema in the neck and left side of the chest.

The child's condition had now deteriorated to the point of extreme fatigue and severe respiratory compromise, leading to the joint decision by the paediatricians and anaesthesiologists that intubation was necessary. The child was premedicated with ketamine, fentanyl and rocuronium bromide and was intubated by an anaesthesiologist 11 hours after admission. Immediately after intubation, condensation was observed in the tube, and the response from end-tidal CO2 measurement indicated correct tube placement. However, there were minimal chest movements and weak, bilateral breath sounds. The child was placed on a ventilator with ketamine and propofol infusion, along with bolus doses of fentanyl and cisatracurium, but required unacceptably high pressures and volumes. As a result, the patient was manually ventilated with 100 % oxygen supplementation. Nevertheless, satisfactory ventilation or oxygenation could not be achieved. Oxygen saturation (SpO2) remained around 70 %. Arterial blood gas at this point showed a pH of 6.8, PO2 16.4 kPa and PCO2 24 kPa.

The university hospital was contacted regarding treatment with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and it was decided to send the ECMO team to the local hospital.

While awaiting the team's arrival, inhaled 20 ppm nitric oxide was administered (1). A new inhalation of 2.5 mg of salbutamol, along with 120 mg of intravenous theophylline and 625 mg of magnesium sulphate was also administered, but no improvement was observed in the patient. Circulatory stability was maintained with an infusion of 0.1 µg/kg/min adrenaline, but there was a life-threatening ventilation issue. It was decided to insert bilateral chest drains due to vital indications, as minimal breath sounds were heard and there were clinical and radiological signs of worsening emphysema. A subsequent chest X-ray showed increasing opacity, pneumomediastinum and emphysema (Figure 2). The antibiotic treatment was changed to a combination of 625 mg of cefotaxime and 120 mg of clindamycin intravenously.

The ECMO team arrived at the local hospital four hours after intubation. Bronchoscopy revealed a significant amount of mucus and swollen mucous membranes. Adequate ventilation was subsequently achieved, allowing transport to the university hospital without ECMO treatment. A pulmonologist at the university hospital performed a bronchoscopy under anaesthesia, which lasted four hours and resulted in the removal of two lodged foreign bodies in the left upper lobe and middle lobe bronchi. These appeared to be fragments of almonds. During a subsequent conversation with the patient's parents, it emerged that the child had eaten granola with almonds at kindergarten two days before admission, the same day the situation became more severe.

The child was extubated after two days in the paediatric intensive care unit. In the following week, the child required high-flow nasal cannula therapy at night, intermittent CPAP treatment during the day and chest physiotherapy. A CT of the chest showed total atelectasis of the right middle lobe and left lower lobe. The child was discharged from the hospital with a plan for inhalation therapy and a subsequent check-up with bronchoscopy.

Discussion

Nuts are the most common cause of foreign body aspiration in children, with the highest incidence between the ages of 1 and 3 years (2, 3). Coughing, wheezing and choking/gagging can be symptoms of foreign body aspiration but may also indicate respiratory infections (3, 4). Fever is typically associated with infections, which our patient did not have. However, CRP was elevated, which is not necessarily the case in foreign body aspiration.

Most children who are evaluated for suspected foreign body aspiration undergo a chest X-ray (> 80 %), and 30–50 % of these are reported to have normal findings (3, 5). Our patient's X-ray showed signs of infection but no suspicion of a foreign body. Given the two-week history of coughing, it is possible, in hindsight, that the child may also have had a mild viral respiratory infection.

The patient may have had partially obstructed airways upon arrival. It is possible that the positive pressure ventilation after intubation displaced the foreign bodies, leading to almost complete airway obstruction and a ball-valve effect, causing the persistently high pCO2 level (6).

Foreign body aspiration can have a fatal outcome (7, 8), and the condition of the child in our case report was life threatening. Bronchoscopy is necessary to remove the foreign body in cases of aspiration (4, 9). Foreign body aspiration should always be considered in children with unusual presentations of respiratory symptoms.

The patient's parents have consented to publication of the article.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Inhaled nitric oxide therapy in children. Paediatr Respir Rev 2005; 6: 190–8. [PubMed]

- 2.

Molla YD, Mekonnen DC, Beza AD et al. Foreign body aspiration in children at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, a two year retrospective study. Heliyon 2023; 9. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21128. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Sink JR, Kitsko DJ, Georg MW et al. Predictors of Foreign Body Aspiration in Children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016; 155: 501–7. [PubMed]

- 4.

Stevens R, Kelsall-Knight L. Clinical assessment and management of children with bronchiolitis. Nurs Child Young People 2022; 34: 13–21. [PubMed]

- 5.

Hutchinson KA, Turkdogan S, Nguyen LHP. Foreign body aspiration in children. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne 2023; 195: E333.

- 6.

Kenth J, Ng C. Foreign body airway obstruction causing a ball valve effect. JRSM Short Rep 2013; 4.. [PubMed]

- 7.

Mîndru DE, Păduraru G, Rusu CD et al. Foreign Body Aspiration in Children-Retrospective Study and Management Novelties. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023; 59: 1113. [PubMed]

- 8.

Rodríguez H, Passali GC, Gregori D et al. Management of foreign bodies in the airway and oesophagus. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2012; 76 (Suppl 1): S84–91. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Fidkowski CW, Zheng H, Firth PG. The anesthetic considerations of tracheobronchial foreign bodies in children: a literature review of 12,979 cases. Anesth Analg 2010; 111: 1016–25. [PubMed][CrossRef]