Konrad Wagner and the conflict at the Department of Anatomy during the occupation

Main findings

During World War II, the Norwegian Nazi Party (Nasjonal Samling) attempted to exploit academic circles in order to promote its ideology, leading to tensions and conflicts at the University of Oslo.

At the Department of Anatomy, prosector Konrad Wagner sought support from the Norwegian Nazi Party in 1941 to have Professor Kristian Schreiner removed from his position.

The conflict created a rift within the department, escalating into a political issue that ultimately led to Wagner's resignation and the end of his research career.

The conflict illustrates how personal disagreements and political pressure can pose a threat to the scientific autonomy of a university during an occupation.

There are many reasons for the continued interest in World War II. Most of those who witnessed the war are now gone, archives are being declassified and new information is coming to light. Moreover, the current international situation brings the threat of war into sharp focus.

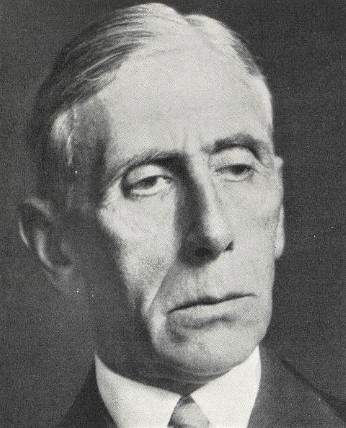

When Norway became involved in the war in April 1940, there was only one university in the country. Initially, the University of Oslo was mostly left in peace, but during the autumn of 1940, tensions mounted (1, p. 166). In September, Norwegian Nazi Party member Professor Ragnar Skancke (1890–1948) was appointed acting Minister of Church and Education, and it did not take long before he clashed with the university leadership (2, p. 108). He lacked authority, both at the university and with the Nazis. This became evident in a conflict at the Department of Anatomy in 1941 (Figure 1). The dispute was primarily between two departmental employees: prosector Konrad Wagner (1900–56), who was pro-German, and Professor Kristian Schreiner, a member of the Norwegian resistance (1874–1957) (Figure 2).

Referred to at the time as 'the Wagner-Schreiner matter', the conflict involved both the Faculty of Medicine and the university's central administration. Wagner felt that he was being excluded from the work at the department. Although the individual events seemed trivial, the conflict threatened to paralyse teaching, exams and other activities at the department (2, pp. 138 - 141). It soon escalated into something much more than a personnel issue, particularly in relation to the power dynamics between the university's leadership and the Ministry of Church and Education, as Wagner and others began contacting Skancke and the Ministry directly, bypassing the usual chain of command. The Norwegian Nazi Party (Nasjonal Samling) sought to use the matter as a platform for a larger political showdown, including attempts to force Schreiner out of his professorship (2, p. 134).

Several sources reference the conflict, and it is described as legendary in the book on the history of the Faculty of Medicine (3). The dispute attracted considerable attention at the time, both within the university and externally (4, 5), and it ended with Wagner resigning. According to the historian Jorunn Sem Fure, who has written about the history of the University of Oslo during the war (2), it was at the Faculty of Medicine that the greatest personal conflicts with political overtones occurred. She highlights the Wagner-Schreiner matter (2, pp. 138 - 141), but no detailed account of it seems to exist.

Material and method

We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, the media archive Retriever, the digital archive of the newspaper Aftenposten, the National Archives of Norway's digital archives and the National Library of Norway's online collection. Jorunn Sem Fure's book about the university during the war has been an important background source (2). The rector of the university at the time, Didrik Arup Seip (1884–1963), published a review of the conflict in his memoir Hjemme og i fiendeland, shortly after the war (6, pp. 143–162).

We examined the University of Oslo's archive in the National Archives of Norway (7). The treason trials with Wagner (8) and Klaus Hansen (9) were accessed via the National Archives' digital archive. Our largest source there is Wagner's treason trial, comprising 421 digitised pages (8). Some documents from the Wagner-Schreiner matter are also stored at the former Department of Anatomy.

Konrad Adolf Wagner

Konrad Wagner was the youngest of seven siblings. His parents established a commercial market garden in Hønefoss in the 1890s, where the large family grew up. As a medical student, Wagner found his calling in physical anthropology, which at that time was a core subject within anatomy. He was employed as an assistant at Oslo University's Department of Anatomy in 1921 (8, p. 400), where he conducted his first scientific work (8, p. 86). This was an assignment given to him by Schreiner: 'What do our skeletal findings from the Middle Ages tell us about the height and proportions of Norwegians at that time?' Wagner was awarded the Skjelderup Gold Medal, a university research prize, for this work in 1924 (10).

Department of Anatomy

After completing his medical degree in 1926, Wagner continued working at the Department of Anatomy. Prosector Jan Jansen (1898–1984) was set to spend two years studying abroad (11), with Wagner standing in for him. Wagner published his first international paper in 1927, which was a continuation of his research as a student. The work entailed an examination of 3534 long limb bones and 73 skeletons (12). This time, he was awarded the Professor Voss Grant (13, p. 85), a prize for medical dissertations. In 1929, Wagner travelled to the United States on a Rockefeller scholarship. Schreiner arranged for him to have 'a place in the laboratory of one of America's renowned anatomists' (8, p. 140), but it is not clear who this was or where Wagner stayed. Upon his return to Norway in 1931, Wagner took up a permanent position of prosector in anatomy. The academic staff consisted of only four people: Professors Schreiner and Otto Lous Mohr (1886–1967), along with prosectors Wagner and Jansen (13, pp. 80–81).

In 1935, Wagner published his first article in English, in which he described a new instrument for measuring the internal skull diameter (14). Once again, he received the Professor Voss Grant, as recognition of this work (13, p. 85). Wagner was clearly not afraid to stand by his professional opinions. As the second opponent in 1935, he sought to reject the doctoral thesis of dentist Ingjald Reichborn-Kjennerud (1901–81). According to newspaper reports, Wagner's critique was 'fierce', sparking a 'rather heated debate' over a lack of rigor in the evidence presented (15). In 1938, he defended his own doctoral thesis 'The Craniology of the Oceanic Races' (16). The study was an analysis of skulls from Oceania, including Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, New Zealand and various groups of islands in the Pacific (17). Many of the skulls stored at the University of Oslo had been collected during an expedition to Australia in the 1890s. Wagner had examined the rest of the material at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. The second opponent, Fredrik Leegaard (1891–1970), stated that it was one of the best academic theses he had ever encountered (18). Wagner was yet again awarded the Professor Voss Grant (13. 86).

In 1939, Schreiner, Mohr and Jansen nominated Wagner for membership in the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. They described his series of anthropological works as being distinguished by 'meticulous thoroughness and a critical evaluation of all results, conducted using modern statistical methods' (19, p. 360).

The Wagner–Schreiner matter

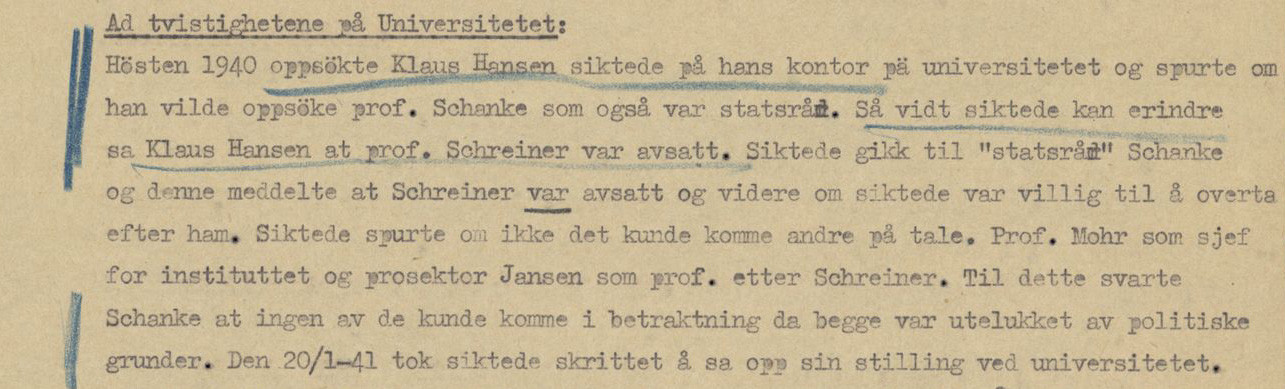

From the autumn of 1940, the authorities attempted to Nazify the university. Two new regulations introduced that autumn would play a significant role in this. In October, the Ministry of Church and Education was granted the right to make political appointments to academic positions, and in December, the state retirement age was lowered from 70 to 65 years. A key, albeit controversial, figure behind the scenes was pharmacology professor Klaus Hansen (1895–1971), who caused considerable turmoil within the faculty and actively supported the German side during the occupation (2). Among his main opponents were none other than the anatomy professors Schreiner and Mohr.

Hansen wrote to Minister Skancke on 20 December pointing out that Schreiner was 66 years old and thus 'fell below the age limit'. The position should therefore be considered vacant. He suggested that a practical solution would be for Schreiner to be dismissed at the end of 1940, with Wagner subsequently taking over (9, p. 175). The minister also wished to dismiss Schreiner, who was a troublesome figure for the occupation authorities. Students who were sympathisers of the Norwegian Nazi Party had repeatedly reported him to the Ministry for making statements that were allegedly politically charged (2, p. 149). At the same time, Wagner was approached by Hansen, who asked if he was willing to contact Skancke about the professorship that would soon be vacant (Figure 3). Wagner did so, but he wanted to 'make it clear to everyone at the university that this was a political appointment'. Given the circumstances, he argued, the appointment would inevitably be seen as political, so this would be the best way to deal with it (8, p. 299).

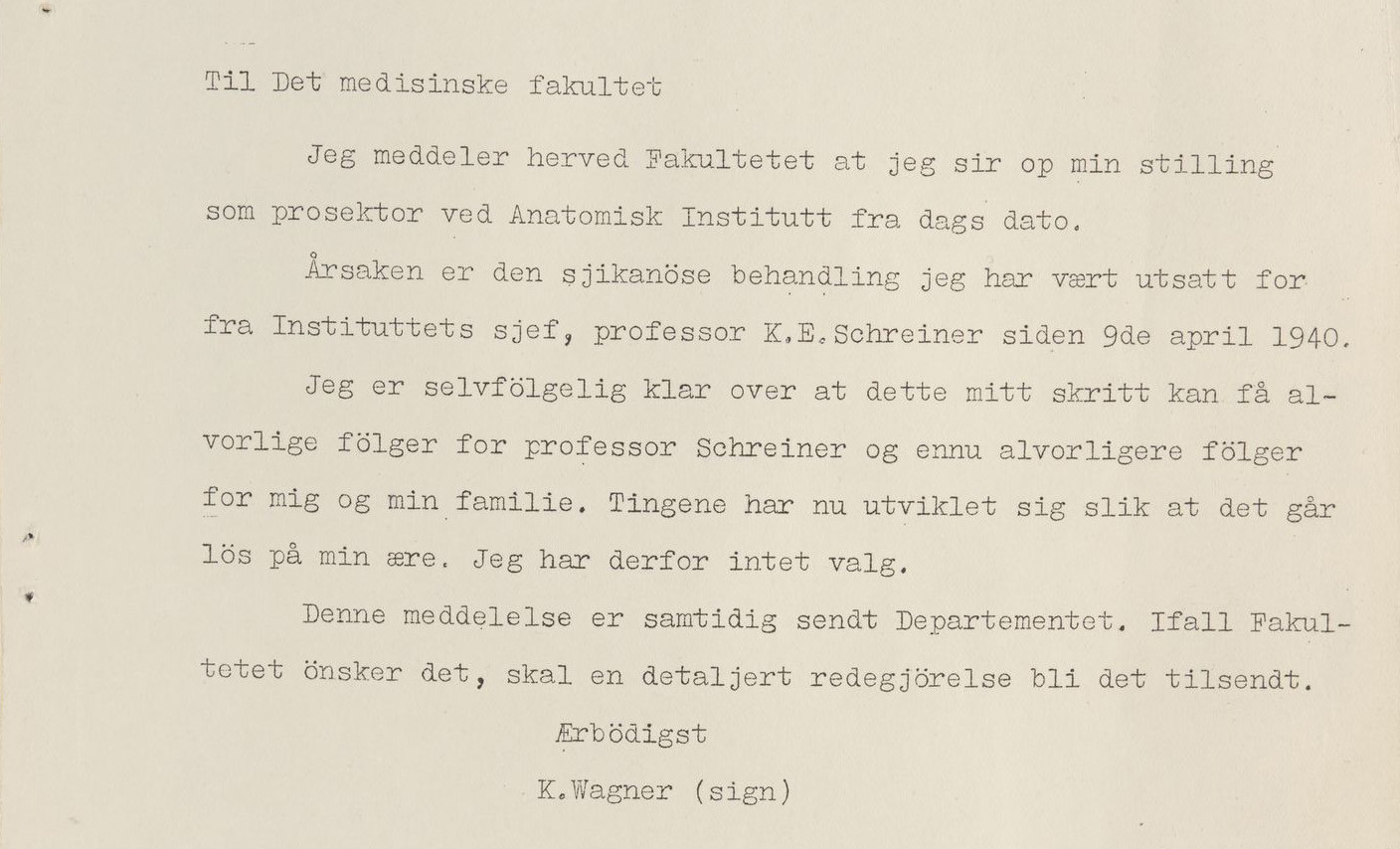

In January 1941, Wagner came into open conflict with his boss and mentor, Schreiner. Wagner resigned from his position on 20 January 1941 (Figure 4). The reason, according to Wagner, was the 'harassment' Schreiner had subjected him to since April 1940, and he believed that 'the political situation' had been a contributing factor (6, p. 58). The criticisms of Schreiner were relatively trivial. Didrik Arup Seip described them as 'ridiculous trivialities' in his memoir (6, p. 148). For instance, Schreiner had conveyed a practice message through a technical assistant with whom Wagner had a strained relationship. Over the winter, the matter escalated, and there was correspondence back and forth and a series of meetings (2, p. 140). Jansen believed the accusations were 'trivialities that seemed ridiculous', but he argued they had to be taken seriously 'because they were being systematically framed within a political context that they in no way had' (Jansen's emphasis) (8, p. 124). Schreiner felt that Wagner had always had a tendency to exaggerate trivial matters (8, p. 144). Initially, Schreiner was prepared to settle the conflict (8, p. 62), but this changed over the course of the winter. 'Any cooperation with a man who has behaved like Dr Wagner is, of course, impossible' (8, pp. 134 - 6). Wagner's behaviour would, under normal circumstances, have led to immediate suspension, wrote Seip, but as things stood, 'we had no choice but to pursue the matter' (6, p. 155). He had clashed with almost all his colleagues, behaved in a threatening manner toward subordinates and been disloyal to the department's leadership (2, p. 140).

The Ministry concluded that 'due to how the situation unfolded, no further action would be necessary'. In April, Wagner was informed that Schreiner's dismissal 'would not be pursued, and the question of appointing him as professor was therefore moot'. Wagner remained formally in his position as prosector until the summer of 1941, but his involvement in teaching ceased in April (8, p. 406–8).

It was not just individual incidents at the department that made the situation unbearable for Wagner. For him, it was excruciating to hear 'all the toxic talk about the things that were dear to me (...) I'm glad that it's finally over' (8, p. 122). Wagner had also been pro-German before the war. This was widely known, but as a scientist, he did not want to take an active part in political activities, and he therefore distanced himself from the Norwegian Nazi Party until September 1941 (8, p. 400). During the situation, Wagner had also renounced his membership in the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. He returned his diploma in February 1941 and asked to be removed from the membership register (19, p. 407).

In the spring semester of 1942, a new chapter in the matter unfolded. A proposal was made to reinstate Wagner as a lecturer in anatomy. Minister Skancke supported the proposal, but the new prorector, Adolf Hoel (1879–1964), advised him to let the matter drop in order to avoid a new major conflict. 'He followed my advice, and Wagner did not return.' (20, p. 50)

The verdict in Wagner's treason trial shows that the court gave a brief and concise description of the events. It describes what happened in April 1940 as 'some episodes' that were relatively insignificant. The judgement states that Wagner perceived this as attempts by Schreiner and Jansen to exclude him from the work at the department, 'which was obviously not the intention'. Wagner misunderstood what had happened, and he exaggerated the episodes, resulting in him acting 'rather recklessly' towards Schreiner. These events, along with Wagner's continued sympathy for the occupying forces and the Norwegian Nazi Party, led to a 'chilly relationship' between Wagner, Schreiner and their colleagues at the department. Wagner felt excluded, and the verdict notes that 'he became nervous and was out of kilter' (8, p. 402).

Why did all this happen?

The history of the university published in 1961 commented on the conflict as follows: 'An attempt to undermine Professor Schreiner by exploiting the poor relationship between him and one of his prosectors, K. Wagner, who was of German descent, was unsuccessful' (1, p. 168). This is not entirely accurate. Everyone agreed that Wagner and Schreiner had had a good relationship. Schreiner had been like a father figure to him, helping and supporting him ever since Wagner arrived at the department 20 years earlier.

At the former Department of Anatomy, there are two copies of Wagner's doctoral thesis with dedications. One reads: 'Dr. med. Jan Jansen, kindly from K.W.,' and the other: 'K. E. Schreiner, from your devoted K. Wagner'. The difference in warmth is clear. It was actually the poor relationship with Jansen that was at the heart of the issue. Schreiner felt that anyone who knew Jansen would find it hard to understand how Wagner could have developed such a deep personal antagonism towards him (8, p. 140). In Schreiner's view, the explanation lay in Wagner's 'long-standing jealousy towards his colleague, a feeling that had intensified as the decision about which of the two prosectors would succeed him drew nearer' (8, p. 140).

This jealousy dated back to the problems that had arisen during Wagner's time in the United States. 'Unfortunately, Wagner behaved in a way that made it impossible to allow him to continue working in the laboratory, and likewise ended any opportunity for his scholarship to be renewed. His conduct also placed me personally in a very uncomfortable position both with the American colleague in question and with the director of the Rockefeller Institute', wrote Schreiner (8, p. 142). The specifics of this are not revealed. This unfortunate situation was in stark contrast to Jansen's studies abroad, which had yielded significant scientific results and brought valuable new insights to the department, profoundly impacting neuroanatomical research in Norway, as noted by Schreiner. Jansen had worked with Professor C.J. Herrick (1868–1960) in Chicago for nearly two years, followed by three months with Professor C.U. Ariëns-Kappers (1877–1946) in Amsterdam (21).

However, Schreiner believed that Wagner's time in the United States had little lasting impact. Wagner had 'looked back with bitterness on his study period in America, which had only brought disappointment and no major scientific results'. Jansen's success after his time abroad, both in securing funding from Rockefeller to build a neuroanatomical laboratory and in attracting young, talented researchers, had been a thorn in Wagner's side. Wagner had mentioned this to Schreiner several times. 'He has painted a picture of the situation he would face if Dr Jansen were to become my successor. The prospect of such a possibility has obviously caused him the utmost concern' (8, p. 142–4).

Wagner and Jansen had known each other for a long time and, in many ways, had kept track of each other's careers. In terms of research, they focused on different branches of anatomy: Wagner on anthropology, Jansen on neuroanatomy. They also took different paths during the war: Wagner became a Nazi, while Jansen was an active resistance fighter (11). Perhaps jealousy played a role, as Schreiner suggested. But since Wagner and Jansen were competing for an upcoming professorship, it could also have been a natural rivalry (2). The conflicts were both personal and political. Schreiner described Wagner as 'a critical and highly competent scientist, well-qualified to take over a professorship in anatomy'. Jansen and Wagner 'were about equal in terms of qualifications', so it was uncertain what outcome a selection committee would reach (8, p. 400). However, in 1945, Jansen emerged as 'the obvious successor to Professor Schreiner' (22). He was the only applicant (23). Wagner found no support in the faculty, which stated that the accusations he had made against Schreiner were highly defamatory and entirely unfounded, and they lamented the use of such unseemly language by one of the university's academics (8, p. 150).

After Wagner left the university, he became the Secretary-General of the Norwegian Medical Association. When the association was Nazified in 1941 and renamed the Norwegian Medical Federation, most doctors terminated their membership (24). Wagner left the Federation in the autumn of 1943 and volunteered for the German medical service. He was called up in January 1944 and assigned to the SS Polizei Division as an Obersturmführer (equivalent to a first lieutenant) (8, p. 30). Before long, he was deployed to Greece for six months, after which he accompanied the German army's retreat through Romania, Hungary and Slovakia (8, p. 162 - 4). In January 1945, he returned home and worked at a German medical practice in Oslo until April 1945 (8, p. 410).

Charges and verdict

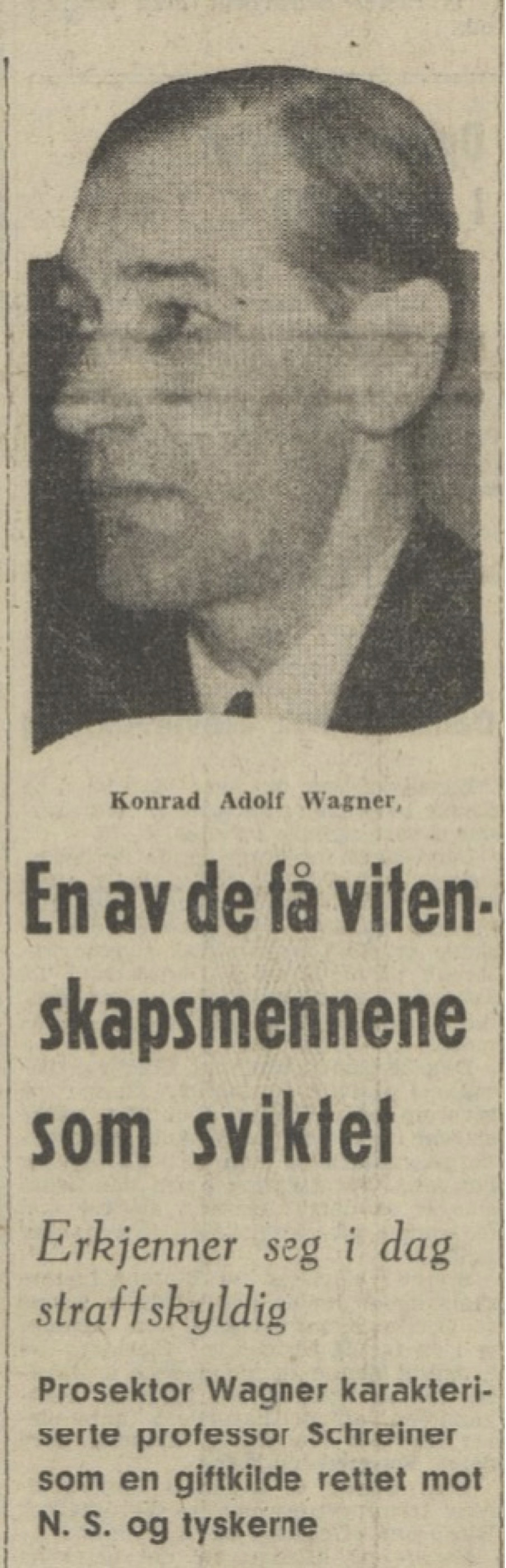

After the war, Wagner was charged with treason. The charges were partly based on his willingness to take over Schreiner's position (8, p. 398) and his membership in the Norwegian Nazi Party from 1941 to 1945. Additionally, in a letter to Minister Schanke in February 1941, Wagner had described Schreiner as a toxic influence working against the Norwegian Nazi Party and the National Socialist movement, accusing him of engaging in anti-state activities (8, p. 114). The case was tried in Oslo City Court over two days in March 1947 (25) (Figure 5). Schreiner was the only witness. Wagner pleaded guilty, which was unusual in treason trials (26).

The verdict differed from the prosecutor's recommendation on several key points. The court agreed with Wagner that there was no evidence to suggest that his letter to Minister Skancke had contributed to Schreiner's arrest in the autumn of 1941 (8, p. 410). As a mitigating factor, the court considered that Wagner had been 'severely impacted by the loss of his scientific career and, consequently, the future he had spent years studying for' (8, p. 412). The court remained detached from the conflicts with Schreiner, noting that the matter had been thoroughly addressed by the university and that it saw 'no reason to examine this aspect of the case further' (8, p. 406). The prosecutor called for a sentence of five years of forced labour and a fine of NOK 25,000. The court agreed with the sentence but reduced the fine to NOK 5000. Wagner was imprisoned twice: first, for nearly a year in custody from May 1945, and later serving his sentence for almost a year from November 1947 (8, p. 365). He was pardoned in March 1949.

The last few years

The prosecutor argued that Wagner should be stripped of his medical licence for ten years, but the court rejected this, referring to 'a number of rulings' from the Supreme Court (27). Wagner advertised in the newspaper as a general practitioner in the spring of 1950, with a practice at his home address in Heggeli, Oslo (28). After that, there is little information about him. When the anniversary book for the students of 1919 was being prepared for their 30-year reunion, he refused to provide any information (29). He later moved back to Hønefoss, remarried in 1952 and died in March 1956 at the age of 55 (30) (Figure 6).

Discussion

The story of Konrad Wagner can be interpreted in several ways. He was a talented doctor and researcher who made things difficult for himself and, due to the war, became entangled in events that spiralled out of control. In a letter to the University Senate dated 20 February 1941, Schreiner wrote: 'The tensions that can arise between people who work together day in and day out over the years is not an extraordinary phenomenon'. However, he also stated that 'the tensions that have occurred at the Department of Anatomy in the last decade are all connected to prosector Wagner's relationships with other departmental employees' (Schreiner's emphasis) (8, p. 88).

Personal conflicts in the workplace are probably no less common today. Perhaps some of them are especially irreconcilable in academia. There are few positions to compete for and many sharp elbows. Was it convenient to push Wagner out when the opportunity arose? There is no evidence of that. For example, as late as 1939, Schreiner and Jansen had ensured that Wagner became a member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters (19, p. 360). Under National Socialism, physical anthropology became politicised, and it is conceivable that this could have caused professional divisions within the department. However, there is no evidence of any significant professional disagreements between Schreiner and Wagner.

When Mohr retired as a professor in 1951, Johan Torgersen (1906–78) was the only applicant to take his place. He had been a prosector at the department since 1946 (31) and had worked primarily in physical anthropology. Race studies and research on physical differences between human types had gained a poor reputation due to misuse and politicisation under National Socialism (32, 33). Consequently, the field of research became marginalised in the post-war period, but Torgersen continued the department's research traditions (32; 33, pp. 310 - 313). This would also have been an opportunity for Wagner if he had been able to continue at the department.

Our article is based solely on written sources, making it challenging to properly assess both the individuals involved and the broader context retrospectively. There are numerous questions we can only speculate on, such as what may constitute post-rationalisations in connection with the court case. However, there is much to suggest that Wagner was perceived as difficult in several relationships: during his study period in the United States, as Secretary-General of the Norwegian Medical Association (24) and at the Department of Anatomy. During the German occupation, the situation was tense, marked by uncertainty and fear, which also affected the work at the university. The divided opinions on the occupying power also created an environment in which conflicts could easily come to the fore and escalate.

In hindsight, it can be said that the Wagner–Schreiner matter had limited impact and no lasting consequences. It did not result in any political gains for Skancke, but it deepened the divide between supporters of the Norwegian Nazi Party and others at the Faculty of Medicine (2, p. 141). Minister Skancke could have imposed his will, but there were limits to how much power the Norwegian Nazi Party could wield without bringing the university's operations to a standstill (2, p. 19). Skancke was sentenced to death for treason, and on 28 August 1948 was the last person to be executed in the post-war trials. Klaus Hansen was sentenced to eight years of forced labour and permanently stripped of his professorship (9, p. 3623).

We would like to thank Per Holck for giving us access to the archives at the former Department of Anatomy.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Universitetet i Oslo: 1911-1961. Del 2. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1961.

- 2.

Fure JS. Universitetet i kamp: 1940-1945. Oslo: Vidarforlaget, 2007.

- 3.

Larsen Ø. Doktorskole og medisinstudium: Det medisinske fakultet ved Universitetet i Oslo gjennom 200 år (1814–2014). Oslo: Det norske medicinske Selskab, 2014: 270.

- 4.

Universitetet i Oslo. Årsberetning 1. juli 1941-30. juni 1942 samt universitetets matrikkel for 1942. Utgitt ved universitetets sekretær. Oslo: A.W. Brøggers boktrykkeri, 1948.

- 5.

Aksjonen mot professor Schreiner ved Anatomisk Institutt. Norsk Tidend (London) 27.5.1941.

- 6.

Seip DA. Hjemme og i fiendeland: 1940-45. Oslo: Gyldendal, 1946.

- 7.

RA-S-2868 - Universitetet i Oslo, Kollegiet. Serie: F - Utskilte arkivserier. Serie: Fe - Universitetet under 2. verdenskrig. Stykke: L0015. Mappe: 0001 - Anatomisk Institutt, bl.a. saken Schreiner - Wagner.

- 8.

Landssvikarkivet, Oslo politikammer, RA/S-3138-01/D/Da/L0416/0004: Dommer, dnr. 2434 - 2440 / Dnr. 2440, 1945-1949: Konrad Adolf Wagner. Arkivverket.

- 9.

Landssvikarkivet, Oslo politikammer, RA/S-3138-01/D/Da/L0898/0002: Dommer, dnr. 3984 - 3985 / Dnr. 3985, 1945-1950: Klaus Gustav Hansen. Arkivverket.

- 10.

4 guldmedaljer utdelt ved universitetets aarsfest idag. Norges Handels- og Sjøfartstidende 2.9.1924: 3.

- 11.

Dietrichs E. Jan Birger Jansen – en grå eminense som har satt spor. Michael 2018; 15 (Supplement 22): 34–42.

- 12.

Wagner K. Mittelalter-Knochen aus Oslo: eine Untersuchung 3534 langer Extremitätenknochen, nebst 73 ganzer Skelette. Skrifter utgitt av Det Norske Videnskaps-Akademi i Oslo. Mat.-naturv. Klasse 1926, no. 7. Oslo: Dybwad, 1927.

- 13.

Getz B. Anatomisk institutt, Universitetet i Oslo: 1815-1965. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1965.

- 14.

Wagner K. Endocranial diameters and indices. A new instrument for measuring internal diameters of the skull. Biometrika 1935; 27: 88–132. [CrossRef]

- 15.

Reichborn-Kjennerud kreert til doktor. Halden Arbeiderblad 7.6.1935: 5.

- 16.

Wagner K. The craniology of the Oceanic races. Skrifter utgitt av Det Norske Videnskaps-Akademi i Oslo. Mat.-naturv. Klasse 1937 no. 2. Oslo: Dybwad, 1937.

- 17.

Doktordisputas. Norsk Magasin for Lægevidenskapen 1938; 99: 890–1.

- 18.

Doktordisputas om hodeskaller. Aftenposten (morgenutgave) 13.6.1938: 4.

- 19.

Amundsen L. Det norske videnskaps-akademi i Oslo 1857-1957. Del 2. Oslo: Aschehoug, 1960.

- 20.

Hoel A. Et oppgjør med landsmenn. Oslo: Minervaforlaget, 1954.

- 21.

Hougen B, red. Studentene fra 1917: biografiske opplysninger samlet til 30-års jubileet 1947. Oslo: Bokkomiteen, 1947.

- 22.

Jan Jansen. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 1945; 52: 437.

- 23.

Universitetet i Oslo. Årsberetning 1. juli 1945-30. juni 1946 samt universitetets matrikkel for 1946. Oslo: A.W. Brøggers boktrykkeri, 1952: 42–59.

- 24.

Haave P. I medisinens sentrum: Den norske legeforening og spesialistregimet gjennom hundre år. Oslo: Unipub, 2011: 140–4.

- 25.

En av de få vitenskapsmennene som sviktet. Dagbladet 11.3.1947: 1, 8.

- 26.

Prosektor Wagner svek universitetsfronten. Aftenposten 11.3.1947: 1.

- 27.

Hem E, Børdahl PE. Ragnhild Vogt Hauge – psykiater, pioner og NS-medlem. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2019; 139: 944–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 28.

Lege. Aftenposten 8.4.1950: 11.

- 29.

Andersen OD, red. Studentene fra 1919: biografiske opplysninger m.v. samlet til 30-års jubileet 1949. Oslo: Aas & Wahls boktrykkeri, 1950.

- 30.

Dødsfall. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 1956; 63: 277.

- 31.

Universitetet i Oslo. Årsberetning 1. juli 1952-30. juni 1953. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1956: 327–42.

- 32.

Larsen Ø. Johan Torgersen. Norsk biografisk leksikon. https://nbl.snl.no/Johan_Torgersen Accessed 20.8.2024.

- 33.

Kyllingstad JR. Rase: en vitenskapshistorie. Oslo: Cappelen Damm, 2023.