Main findings

In the period from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2022, the number of locum contracts in Regular GP surgeries in Norway increased from 916/year to 5003/year (446 % in total).

The largest increase in locum contracts per regular general practitioner (GP) list (at 669 %) took place in the least central municipalities. Here, the locum periods also tended to be of shorter duration, applied to full-time positions and were more often linked to lists with no permanent GP.

The workload of GPs is increasing (1), and the county governors, municipalities and the GPs themselves have expressed concern about the sustainability of the Regular GP Scheme (2). Problems in recruiting doctors are encountered both in the least central and the most central municipalities in Norway (2). Figures from the Norwegian Directorate of Health showed that as of November 2023, altogether 216 052 inhabitants had no regular GP (3).

The high number of inhabitants who have no permanent GP is described as a crisis for the Regular GP Scheme (4, 5).

Locum doctors add flexibility to the Regular GP Scheme (6). A locum doctor is a substitute doctor with authorisation who fills a completely or partly vacant position over a limited period of time (7). There may be several reasons for the use of locum doctors (8). In the Regular GP Scheme, substitution normally occurs when a GP is absent because of specialisation training, parental or sick leave, or other work, such as research. A study conducted in 2014 showed that 65 % of the locum contracts were in full-time positions (8).

Shortage of GPs in the municipalities is a further important reason for using locums. Many regular GPs resign, more of them retire at an earlier age, and there are problems in recruiting new GPs (9). The number of doctors registered in the 'locum' category in the GP Registry increased from 1 157 in 2017 to 1 710 in 2021, an increase of 48 % (10). Frequent use and change of locums may weaken the continuity of the doctor-patient relationship, which for patients is associated with increased use of health services and medication, as well as higher mortality (11).

In the regular GP service, the proportion of consultations that listed inhabitants have with their own GP in the course of one year has remained stable in Norway over time: from 63 % in 2006 to 65 % in 2021 (12). There were nevertheless some geographical variations in this proportion, whereby 46 % of the consultations in the regular GP service took place with patients' own GP in the least central areas and 70 % in the most central areas in 2021. This is because inhabitants in the least central areas tend to be more frequently entered on lists that have no permanent GP than inhabitants in the most central areas.

There is little evidence-based knowledge about the recruitment, organisation, use and consequences of locum doctors in the regular GP service (8, 9, 13). The GPs and the municipalities are completely dependent on locum doctors to provide adequate available health services (14). The locums cover a staffing shortfall that will occur at any time. An international review article from 2019 points out that much of the research on the use of locum doctors is flawed and of low quality, and that there is limited empirical support for common assumptions regarding lower quality and poorer patient safety arising from the use of locum doctors (15). The objective of this study was to investigate the scope and prevalence of registered locum contracts in the Regular GP Scheme in the years 2016‒22, with a particular focus on their distribution by centrality.

Material and methods

Data material

We applied to the GP Registry for data for all regular GP lists and associated locum contracts. The GP Registry contains data going back to 2001, but short-term locum contracts were not registered until 2016. The changes to registration practices came into force in 2016, after which locum contracts for a duration of at least one month and 20 % of a full-time position were entered into the registry. In 2018, this was further specified to apply to all locum contracts down to one day's duration. We chose to restrict our analyses to the period from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2022.

The GP Registry provided us with two data sets – lists of regular GPs and lists of locum contracts. The lists of regular GPs contained the variables contract ID, municipality number and whether the list had a permanent GP or not. Lists of regular GPs with a permanent doctor specified the doctor's gender, specialty, permanent salary (yes/no) and age. The lists of locum contracts contained contract IDs, start and end dates and percentage of full-time position. Locum contracts with insufficient information on the percentage of full-time position were excluded. As regards position percentage, we chose to split the locum contracts into two groups: those that applied to a 100 % position and those that applied to a smaller full-time percentage. Using the contract ID as the key, the data sets were linked in the SPSS statistics application (IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 28.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Analyses

We have used Statistics Norway's centrality classes for municipalities (16), which is based on travel time to workplaces and service functions in all inhabited census units. Municipalities in centrality class 1 are most centrally located, and municipalities in centrality class 6 are least central. We have grouped the municipalities in three composite groups by centrality (1‒2, 3‒4 and 5‒6). Furthermore, within these composite centrality groups we have compared the development in registered locum contracts, the duration of these contracts and the percentage of full-time work. Since locum doctors mainly substituted for GPs who were absent from their own list, and to highlight trends in the various centrality groups, we divided the number of locum contracts by the number of GPs in each centrality class (17).

The duration of the locum contracts was calculated from the start and end dates, and was reported in number of days. We estimated the mean and a 95 % confidence interval (CI) for duration in the different centrality groups.

Research ethics

Sikt – Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research has approved the data management plan and the data protection measures for the study (ref. #702775, dated 18 November 2021). All information has been processed anonymously and in compliance with the data protection regulations.

Results

Prevalence of locum contracts

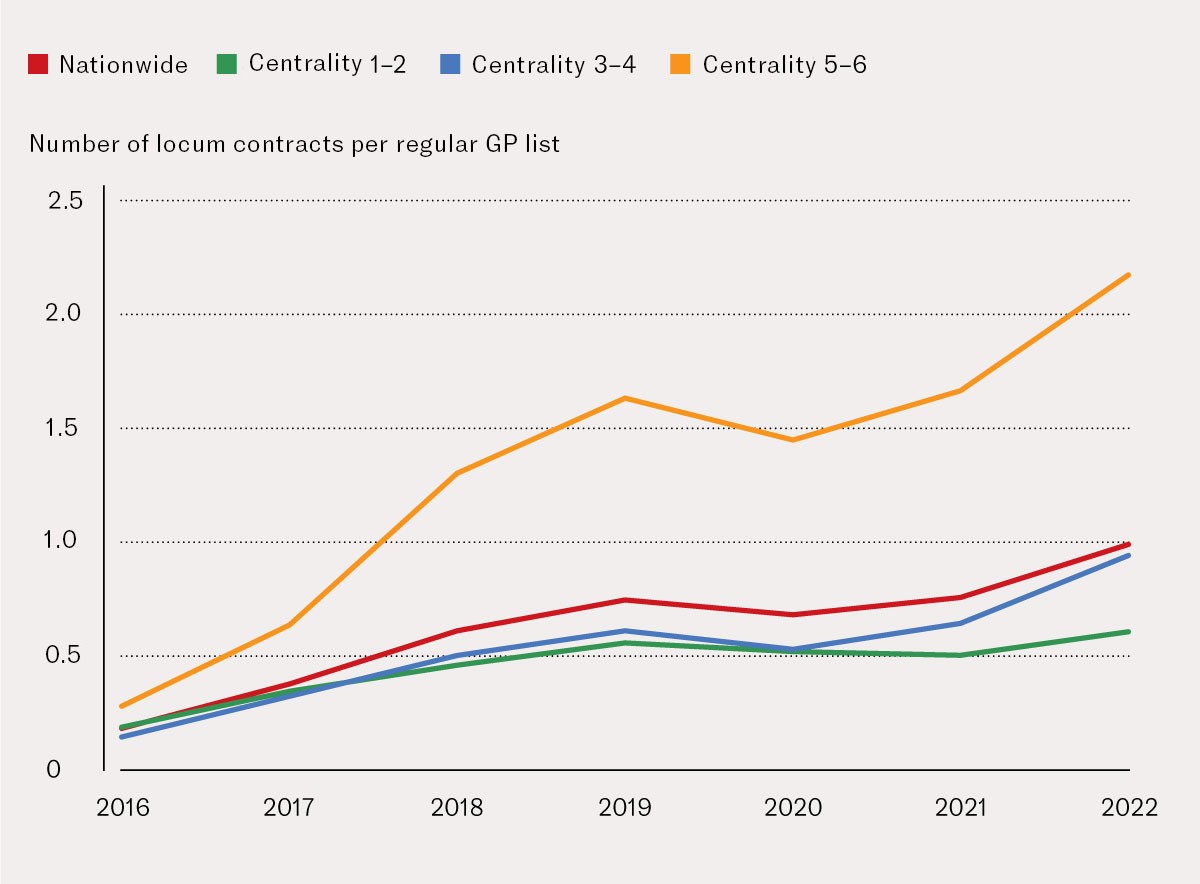

A total of 38 617 regular GP lists with unique contract IDs and 21 541 associated locum contracts were registered in the period from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2022. Altogether 123 locum contracts had no information on percentage of full-time position and were therefore excluded, so that the analyses were based on 21 418 locum contracts. During the period studied, the number of registered locum contracts increased from 916 in 2016 to 5003 in 2022 (446 % in total). Figure 1 shows the development in registered locum contracts per year divided by the number of regular GP lists in Norway as a whole and in the different centrality groups. The increase from 0.282 in 2016 to 2.17 in 2022 was highest in centrality group 5‒6 (669 % in total).

Duration of locum contracts

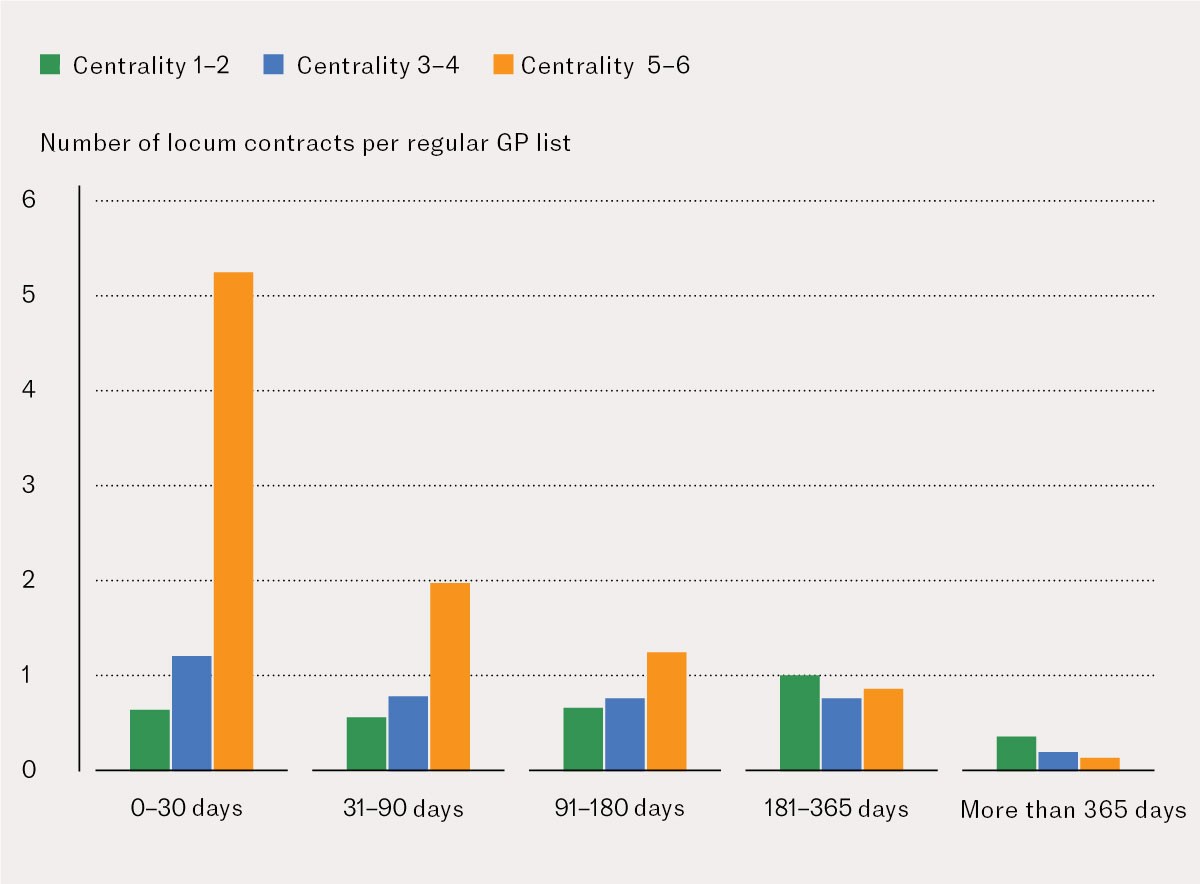

Figure 2 shows how the duration of locum contracts per regular GP list varied by centrality. On average, the locum periods in centrality group 1‒2 were 195 days (95 % CI: 190‒200); in group 3‒4, 130 days (95 % CI: 127‒134), and in group 5‒6, 67 days (95 % CI: 64‒69)

Percentage of full-time equivalent in locum contracts

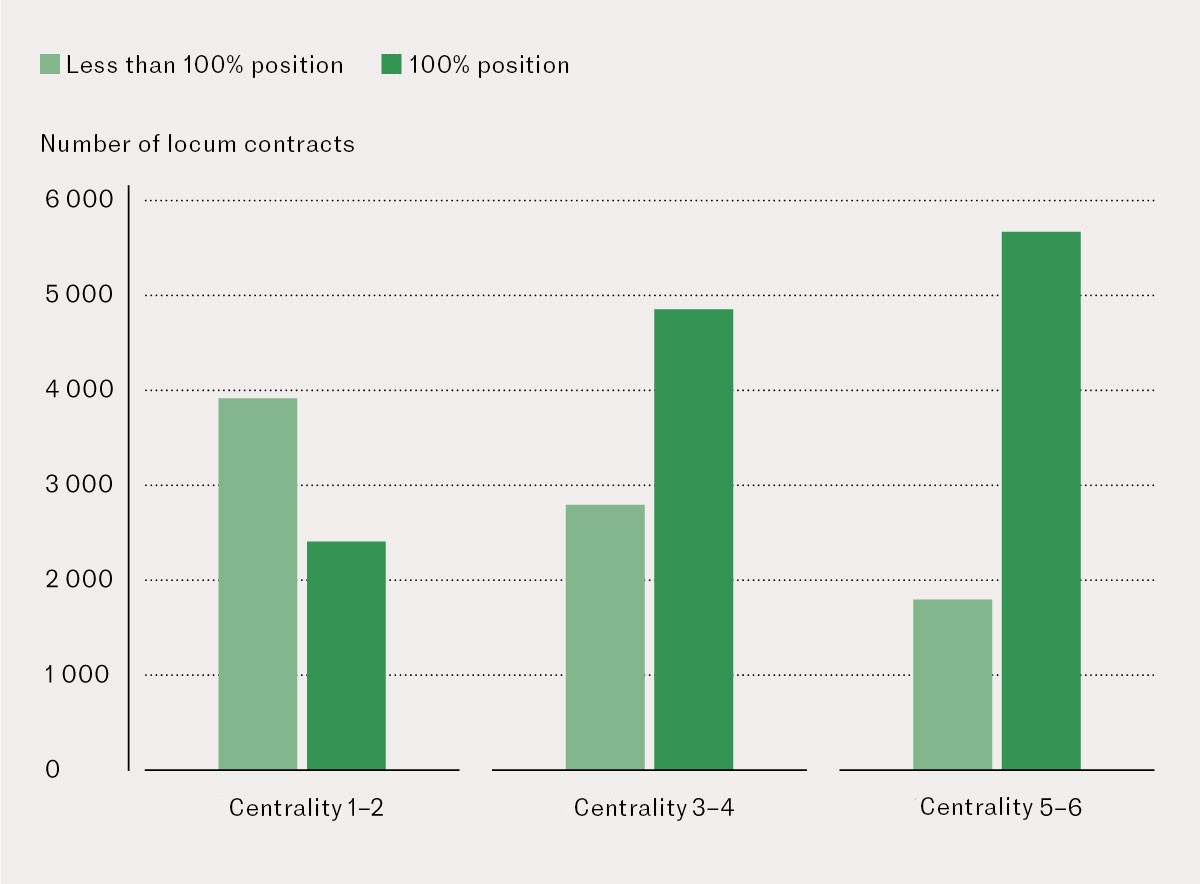

Figure 3 shows the percentage of full-time equivalent in the locum contracts by the different centrality groups. In centrality group 5–6, the proportion of locum contracts for full-time positions was 100 % higher than in centrality group 1–2.

Locum contracts for lists with no permanent GP

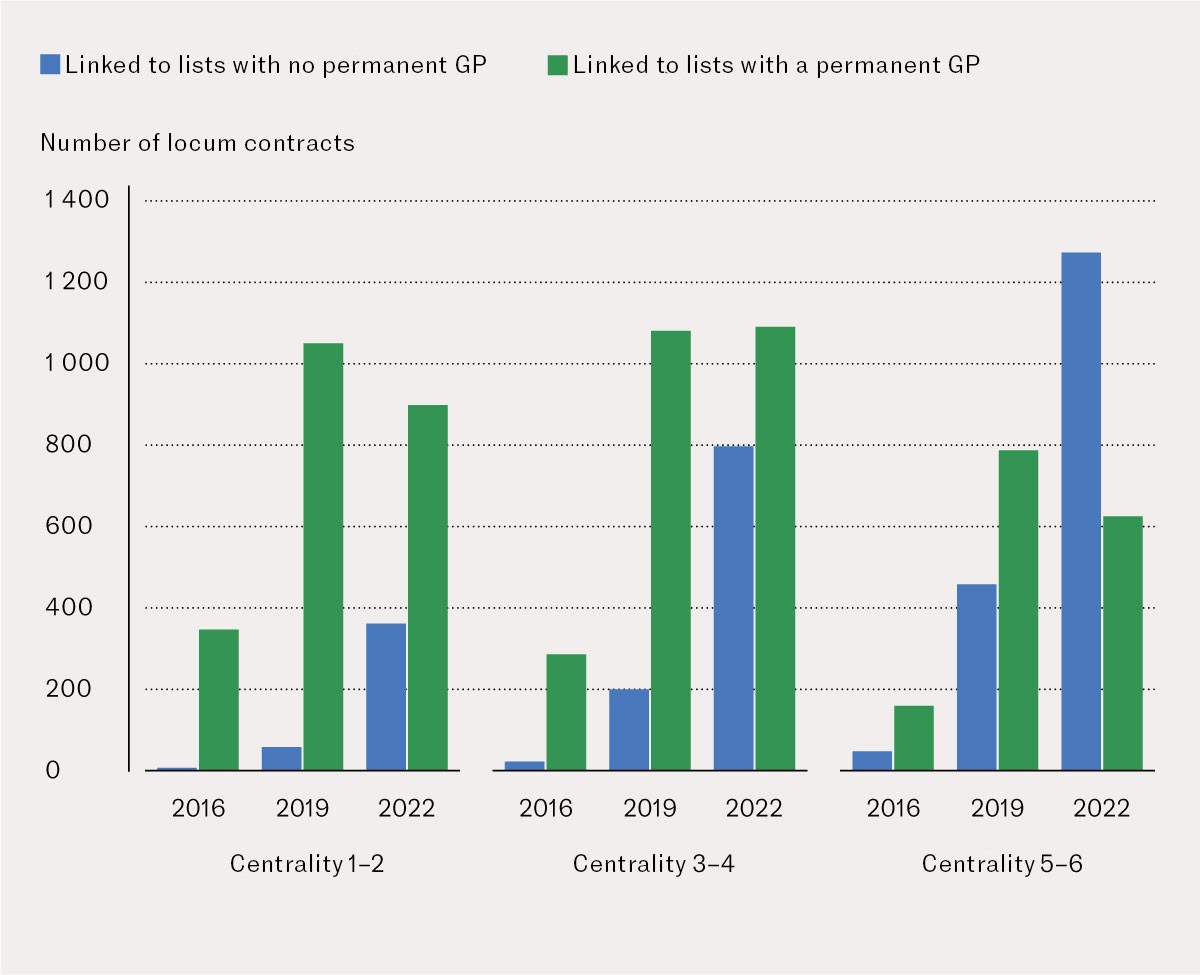

In the study period, the number of locum contracts per list with no permanent GP increased from 0.5 in 2016 to 4.7 in 2022 (by 840 % in total). Figure 4 shows the number of locum contracts linked to lists with and without a permanent GP in 2016, 2019 and 2022. The number of locum contracts linked to lists that had no permanent GP increased by 50 locum contracts per year on average (108 %) in centrality group 1–2, by 111 locum contracts (97 %) in centrality group 3–4, and by 175 contracts (80 %) in centrality group 5–6. For locum contracts linked to lists with a permanent GP, the average annual increase in the respective centrality groups amounted to 79 (21 %), 115 (32 %) and 66 (36 %) locum contracts.

Discussion

Using data from the GP Registry, this registry study finds that the annual number of locum contracts in Norway has increased by 446 % from 2016 to 2022. The relative increase was highest in rural areas, with a 669 % increase in the number of locum contracts per regular GP list during the study period in centrality group 5–6. Short duration of the locum contracts and a growing number of lists with no permanent doctor are driving up the use of locums in the least central areas when compared to more centrally located areas. The locum contracts in central areas are characterised by lower percentages of full-time positions and longer duration.

These findings are in line with the study undertaken by the Norwegian Directorate of Health in 2022, which links the increase in the use of locums to the growth in the number of lists with no permanent doctor (18). Furthermore, the national quality indicator Duration of the municipality's contracts with regular GPs shows that nationwide, the median duration of regular GP contracts fell from 9.3 years in 2016 to 7.8 years in 2022. This adds to the impression of reduced continuity in the regular GP service at the national level (19). The quality indicator has not been estimated at the municipal level for the different centrality classes.

Stringer et al. (6) claim that the use of locums will continue increasing, because the locums are better paid, have a smaller workload and greater autonomy than permanently employed doctors. In Norway, some learning objectives in the new specialist training programme in general practice (the institution service) imply that specialty registrars will need a locum for at least six months. Parental and sickness leave among doctors also contribute to the need for locums. The analyses show that the use of locums levelled off in 2020–21, possibly because of changes in the pattern of absence resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic (fewer doctors on educational leave and less access to locums from Sweden and Denmark because of closed borders). An increasing need for locums could be associated with higher workloads, meaning that partly, regular GPs need relief in the form of part-time locums, and partly that regular GPs resign from their position and it may take some time before permanently employed doctors can take over their lists.

Authorities in the UK have been taking the challenges involved in increased use of locums seriously, and in 2018 they produced a practical guide for the use of locum doctors (20). For the above reasons and based on our findings, we believe that such a guide, adapted to the Norwegian health services in rural and urban areas, could be useful. The municipalities spend a lot of time and resources on searching for, hiring and following up locums. A guide could provide useful support for these efforts.

Some municipalities are making deliberate efforts to reduce the need for locums. Nordkapp municipality has successfully practised a supernumerary approach in its regular GP service (21). Another example is Senja municipality, where the municipality has attempted to reduce the use of locums by increasing basic staffing levels, curtailing the patient lists, adapting the working day and introducing rotation positions for GPs (also known as 'North Sea positions' (22). The municipal administration assumes that this will give the doctors more time for their patients, flexible solutions adapted to each doctor and thereby a reduced need for locums.

Registration practices for locum contracts before 2016 have undoubtedly limited the management information available to the health authorities regarding the true use of locums in the Regular GP Scheme. The tightening of the registration practice means that the observed increase may be conditioned by this change. We believe that the amendment to the registration practice in 2018 has been less significant than the change introduced in 2016, and deem it to have been insightful to study the period 2016‒2022. A further weakness is that the GP Registry does not distinguish between different types of locums ‒ whether they are permanent locums, employed by the municipality or leased from a temporary staffing agency. Nor did we have access to other descriptive data on the locums. Our analyses were unable to identify locum contracts that applied to the same doctor on multiple occasions, or whether the same locum held several different positions with a low full-time equivalent percentage for different regular GP lists in the same surgery. We are thus unable to draw any conclusions when it comes to continuity.

Conclusion

This study shows that the GP Registry contains useful nationwide information on the prevalence and development of locum contracts in the Regular GP Scheme from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2022, but lacks details that can provide more insight into this essential part of the labour force in the health services. We found geographical variations, whereby the least central areas of the country had the highest proportion of locum contracts per regular GP list, the highest growth, the shortest duration and largest full-time equivalent percentage when compared to more centrally located areas. Increased use of locums in the Regular GP Scheme in the least central areas represents a challenge to equal access to health services. Future research should focus on revealing the causes of increased use of locums, the reasons why some doctors choose to work as locums, as well as the consequences to the patients of increased use of locums. The use of locums should also be elucidated from the perspective of other users, such as the municipal and other healthcare personnel in the regular GP surgeries, out-of-hours services and nursing homes.

This project was funded by the Norwegian Medical Students Association, the Programme for Research on Rural Medicine ('The Programme') and the Norwegian Centre for Rural Medicine.

The article has been peer reviewed.

- 1.

Theie M, Lind L, Skogli E. Fastlegeordningen i krise - hva sier tallene Oslo. https://www.legeforeningen.no/contentassets/1f3039425ea744adab5e11ac5706b85a/fastlegeordningen-i-krise-hva-sier-tallene-endelig-rapport.pdf Accessed 26.10.2021.

- 2.

Helsedirektoratet. Handlingsplan for allmennlegetjenesten Årsrapport 2021. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/handlingsplan-for-allmennlegetjenesten-arsrapport-2021 Accessed 22.3.2023.

- 3.

Helsedirektoratet. Handlingsplan for allmennlegetjenesten - månedsrapport november 2023. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/handlingsplan-for-allmennlegetjenesten-manedsrapport-november-2023 Accessed 25.11.2023.

- 4.

Allmennlegeforeningen. Utfordringene i fastlegeordningen. https://www.legeforeningen.no/foreningsledd/yf/allmennlegeforeningen/krisen-i-fastlegeordningen/ Accessed 1.4.2023.

- 5.

Sæther A, Nærø A. Kampen om fastlegene. VG 2017. https://www.vg.no/spesial/2017/fastleger/ Accessed 26.10.2021.

- 6.

Stringer G, Ferguson J, Walshe K et al. Locum doctors in English general practices: evidence from a national survey. Br J Gen Pract 2023; 73: e667–76. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Helfo. Vikar for lege. https://www.helfo.no/lege/avtale-om-direkte-oppgjor-for-lege/vikar-for-lege Accessed 5.2.2022.

- 8.

Abelsen B, Gaski M, Brandstorp H. Vikarbruk i fastlegeordningen. https://www.utposten.no/asset/2016/2016-06-30-33.pdf Accessed 1.2.2022.

- 9.

Grigoroglou C, Walshe K, Kontopantelis E et al. Locum doctor use in English general practice: analysis of routinely collected workforce data 2017-2020. Br J Gen Pract 2022; 72: e108–17. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Pedersen K, Godager G, Rognlien HD et al. Evaluering av handlingsplan for allmennlegetjenesten 2020–2024: Evalueringsrapport I, 2022. https://osloeconomics.no/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/HPA-evalueringsrapport-2022.pdf Accessed 5.7.2023.

- 11.

Sandvik H, Hetlevik Ø, Blinkenberg J et al. Continuity in general practice as predictor of mortality, acute hospitalisation, and use of out-of-hours care: a registry-based observational study in Norway. Br J Gen Pract 2022; 72: e84–90. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Delalic L, Grøsland M, Gjefsen HM. Kontinuitet i lege-pasientforholdet, Kunnskapsgrunnlag til Ekspertutvalget for gjennomgang av allmennlegetjenesten. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/6713b23f64b7482780fd013e63397516/kontinuitet-i-lege-pasientforholdet-kunnskapsgrunnlag-rapport-2023.pdf Accessed 2.7.2023.

- 13.

Harbitz MB, Stensland PS, Gaski M. Rural general practice staff experiences of patient safety incidents and low quality of care in Norway: an interview study. Fam Pract 2022; 39: 130–6. [PubMed]

- 14.

EY og Vista Analyse. Evalueringen av fastlegeordningen. https://vista-analyse.no/site/assets/files/6663/evaluering-av-fastlegeordningen---sluttrapport-fra-ey-og-vista-analyse.pdf Accessed 1.7.2023.

- 15.

Ferguson J, Walshe K. The quality and safety of locum doctors: a narrative review. J R Soc Med 2019; 112: 462–71. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

SSB. Standard for sentralitet. https://www.ssb.no/klass/klassifikasjoner/128 Accessed 25.3.2022.

- 17.

Statistisk sentralbyrå. Kommunehelsedata. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/12720/ Accessed 2.2.2023.

- 18.

Helsedirektoratet. Oppfølgning av Handlingsplan for allmennlegetjenesten 2020-2024, kvartalsrapport 4. kvartal 2021.https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/oppfolging-av-handlingsplan-for-allmennlegetjenesten-2020-2024-kvartalsrapport-4.kvartal-2021 Accessed 1.10.2023.

- 19.

Abelsen B, Gaski M, Brandstorp H. Varighet av fastlegeavtaler. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2015; 135: 2045–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Chapman R, Cohen M. Supporting organisations engaging with locums and doctors in short-term placements: A practical guide for healthcare providers, locum agencies and revalidation management services. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/supporting_locum_agencies_and_providers.pdf Accessed 2.4.2023.

- 21.

Gaski M, Abelsen B. Fastlegetjenesten i Nord-Norge. https://www.nsdm.no/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Endelig-versjon-3-mai-2018-Rapport-om-fastlegetjenesten-i-Nord-Norge.pdf Accessed 1.12.2023.

- 22.

Skoglund K, Hansen P, Andersen M et al. Har ansatt åtte leger på kort tid – mener de kan ha knekt koden på fastlegekrisa. NRK 22.8.2023. https://www.nrk.no/tromsogfinnmark/senja-kommune-mener-de-har-knekt-koden-pa-fastlegekrisa-1.16524464 Accessed 1.9.2023.