A woman in her forties developed left-sided pain in her ear and pharynx, which worsened when swallowing and talking. Multidisciplinary assessment led to a final diagnosis, which turned out to be a rare condition for which early detection is crucial for a favourable treatment outcome.

A woman in her forties was referred to a maxillofacial surgery department by a dental specialist in oral surgery. The woman had a history of asthma and used an inhaler with asthma medication (ipratropium bromide 40 µg × 4, beclomethasone/formoterol 100/6 µg up to × 4 as needed) and a contraceptive pill. She did not smoke or use snus and did not drink alcohol. She reported that two months earlier she had a relatively rapid onset of left-sided ear fullness. She consulted her GP, who put her on sick leave and prescribed a course of antibiotics (phenoxymethylpenicillin 660 mg × 4 perorally for one week) due to suspected otitis media. Four days later, she experienced severe pain in the external auditory canal on the same side. Mild redness was observed in the ear canal, but there was no rash or other signs of external otitis, and C-reactive protein (CRP) was < 5 mg/L (reference range 0–4). She remained afebrile upon repeated examination by her GP.

Otalgia and a sensation of fullness can occur in various conditions, including acute otitis media, external otitis, cerumen obliterans and other obstructive processes in the ear. Examination of the outer ear and otoscopy should be performed. Furthermore, maxillary sinusitis can, in rare cases, cause referred pain from the ear via the trigeminal nerve (1). However, with sinusitis, symptoms such as nasal discharge and/or congestion and possibly fever would be expected.

Ciprofloxacin/fluocinolone acetonide ear drops (2 mg/mL) were tried twice a day for a week to treat redness in the ear canal, and decongestant phenylpropanolamine tablets (50 mg × 2 as needed) were prescribed for suspected sinusitis. Due to the lack of improvement, the patient returned to her GP four days later, who prescribed a combination nasal spray with antihistamine and corticosteroid (Dymista, 137 µg/50 µg × 2) and clindamycin capsules (150 mg × 4 for one week). However, this still did not alleviate the symptoms and the patient was subsequently referred to the Department of Otolaryngology. A CT of the head, sinuses and neck with intravenous contrast was performed, with normal findings except for possible pathology in the second molar in the upper left jaw (tooth 27). The patient was referred to a dental specialist in oral surgery for an assessment of dental status and the temporomandibular joint. The oral surgeon found no evidence of pathology in the teeth. A clinical examination of the temporomandibular joint was conducted, and for diagnostic purposes, local anaesthesia was administered to the left temporomandibular joint without relieving the pain.

A variety of conditions in the oral cavity can cause facial pain, such as odontogenic infections, cracks and fractures in teeth and other oral medical conditions (2, 3). As these were ruled out through clinical examination, an examination of the temporomandibular joint and surrounding structures was performed. Temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) is an umbrella term for various diagnoses in the temporomandibular joint and surrounding structures, such as temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis, disc displacement, arthritis and myalgia of the masticatory muscles. Symptoms and findings vary depending on the specific diagnosis, but pain during opening and chewing, trismus and clicking or grinding sounds are common. Ear symptoms are also common in these patients. This may be due to the close anatomical relationship or shared nerve innervation (4), and a sensation of fullness or pressure in the ear occurs in about three-quarters of patients (5). Ear pain has been reported as present in over half of those with TMD (5). Although our patient experienced pain and a sensation of fullness, both clinical examination and imaging found no indication of symptoms being due to TMD.

The oral surgeon referred the patient to the maxillofacial surgery department. During consultation with the maxillofacial surgeon, the patient stated that the pain had gradually worsened and was affecting her sleep. She said that talking and swallowing triggered the pain and that it could last from minutes to several hours. No facial redness or swelling was observed. Upon examination, palpation tenderness was noted in the ear canal and numbness in the left nasal floor, along with reduced sensitivity in the posterior third of the tongue on the left side, and a burning sensation when touching the palate on the same side. No pain upon palpation of the styloid processes in the tonsil and posterior pharyngeal wall (which can be present in pain caused by elongated styloid processes, known as Eagle syndrome) (6).

The findings gave reason to suspect neuropathic pain in the supply region of the glossopharyngeal nerve.

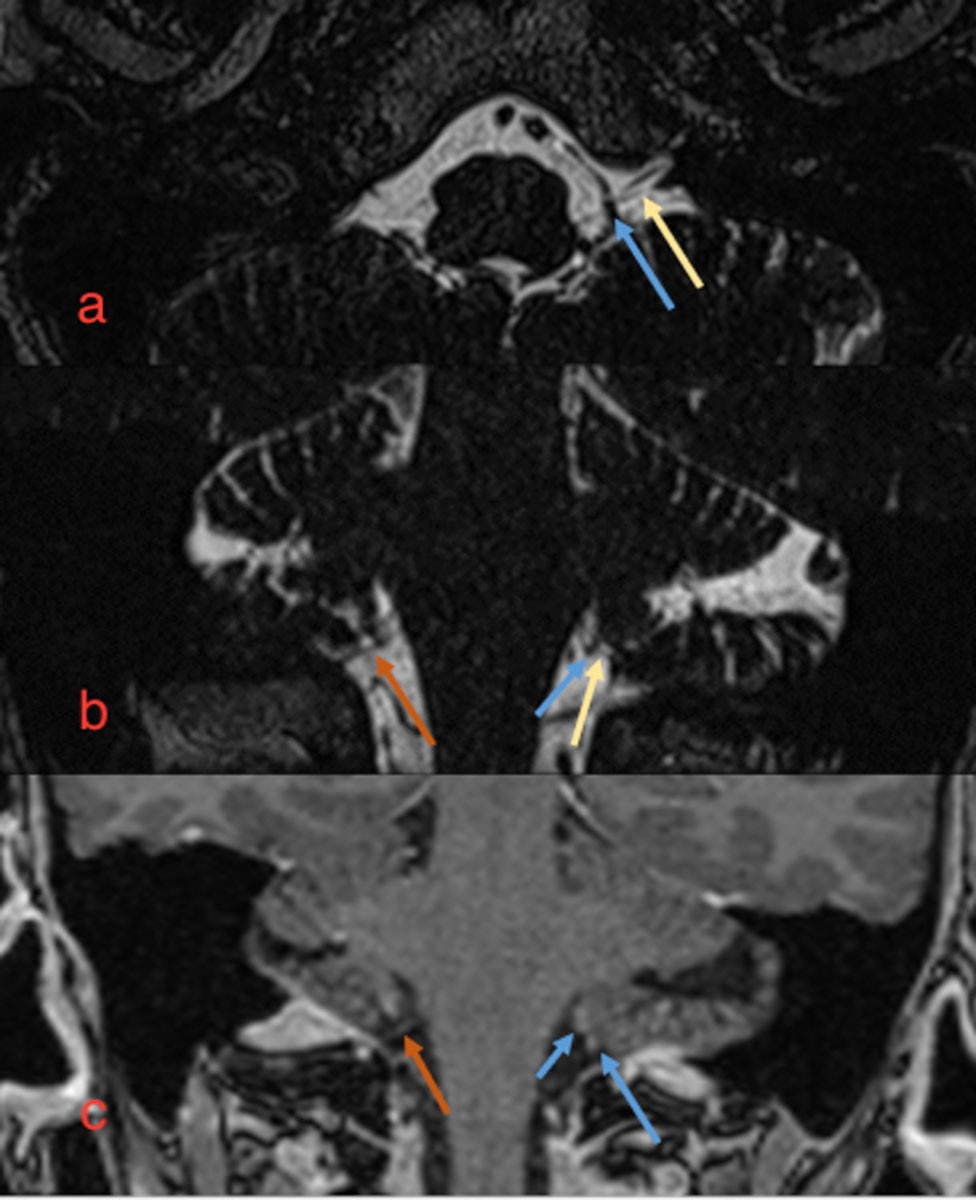

The maxillofacial surgeon suspected glossopharyngeal neuralgia and referred the patient for MRI with intravenous contrast to assess whether there were signs of nerve compression from surrounding blood vessels. MRI (3D T2 turbo spin echo and fat-suppressed T1 after intravenous contrast) of the head and skull base revealed asymmetry around the glossopharyngeal nerve. The course of the nerve on the right side was unremarkable, while several small vascular structures were observed along the nerve on the left side at the cerebellopontine angle. These were interpreted as small pial veins (Figure 1). No arteries were observed in relation to the nerve or signs of denervation of the stylopharyngeus. A small, round contrast uptake was noted at the dura in the foramen magnum on the left side, prompting further examination with CT angiography of pre- and intracerebral vessels to rule out an aneurysm. CT showed normal pre- and intracerebral arteries and no aneurysmal dilation of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. Bilateral elongated styloid processes were observed.

The MRI and CT findings strengthened the suspicion of glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Due to elongated styloid processes, Eagle syndrome was considered as a differential diagnosis. However, there was no direct tenderness upon intraoral palpitation, and the pain was not triggered by neck rotation and lateral bending, as is typical for the condition. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia was therefore considered the most likely diagnosis.

The patient was referred to a neurologist who initiated treatment with carbamazepine (200 mg × 2) for neuropathic pain, but this was discontinued due to adverse effects in the form of abdominal pain and constipation. The neurologist noted that the patient was now experiencing left-sided pain in the ear and throat throughout the day. The pain could improve for a few hours during the day, only to reoccur. The patient was still on sick leave due to the pain and was unable to perform her daily activities. Neurological examination confirmed sensory loss in the tongue and palate, and there was loss of pharyngeal reflex on the left side. Pregabalin (50 mg × 3) was prescribed.

Due to the intolerable pain, and in order to further investigate the condition, the patient was admitted to the neurology department two months after the initial assessment by the maxillofacial surgeon and three months after the onset of symptoms. At that time, she had been on pregabalin for three days with no improvement. A weight loss of 6.5 kg was reported since the onset of pain. Besides the impairments in the pharynx and palate, the neurological examination was normal. The patient underwent a chest CT, spinal puncture and blood tests to rule out neuroinflammatory and infectious causes, such as neurosarcoidosis and neuroborreliosis. All findings were normal, and her SARS-CoV-2 test was negative.

The patient was started on oxcarbazepine (titrated up to 300 mg × 2) for pain relief. She was also prescribed a 'cream mixture' consisting of 10 mL paracetamol syrup (24 mg/mL) and 10 mL of Xylocain gel (2 %) mixed with a little cream, which she could take 20–30 minutes before each meal. Eleven days after discharge, the patient contacted the neurology department again. She was distressed due to the worsening pain in her throat, palate and left ear, along with increasing problems with eating and drinking. The pain made it difficult for the patient to talk and use her mouth, and her swallowing was severely restricted.

The symptoms were interpreted as an exacerbation of the underlying condition, with the pain profile evolving from trigger-induced, paroxysmal pain to more continual pain with paroxysmal exacerbation.

The patient was recommended further titration of oxcarbazepine and an increase in the frequency of the cream mixture. Paracetamol 1 g × 4, etoricoxib 90 mg × 1 and amitriptyline 25 mg × 1 were also prescribed. The patient was referred for evaluation for decompression surgery due to glossopharyngeal neuralgia and was assessed by a neurosurgeon five months after the onset of symptoms. The condition was diagnosed as glossopharyngeal neuralgia with neuropathy. The clinical picture was deemed consistent with the MRI findings of arteries adjacent to the glossopharyngeal nerve on the left side, and the patient was referred for microvascular decompression surgery. Surgery took place six months after the onset of symptoms. Peroperatively, a large calibre vein was found along the entire course of the glossopharyngeal nerve on the left side, consistent with the MRI findings. The vein was separated and fixed away from the nerve. The postoperative period was uneventful, except for some nausea and dizziness. The patient was discharged to a local hospital after two days for further mobilisation. At a neurology check-up eleven weeks after surgery, the patient reported a significant improvement in pain, with shorter and less intense episodes than previously. One year after surgery, she experienced further improvement, and two years after surgery she continues to improve. She still sometimes experiences discomfort when exposed to the cold and when feeling tired. She underwent rehabilitation to normalise tongue and swallowing motor function, and her body weight has returned to normal (following a total weight loss of 10 kg up to the operation).

Discussion

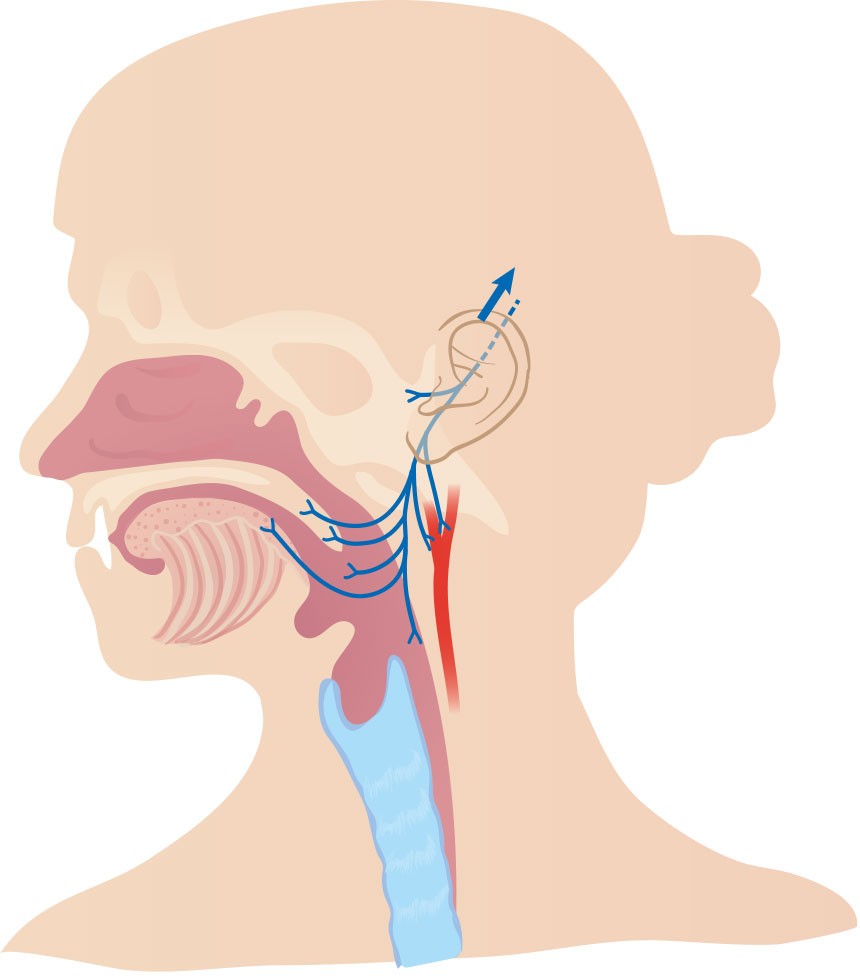

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is a rare condition that causes pain in the innervation area of the ninth cranial nerve, the glossopharyngeal nerve (Figure 2). The annual incidence of the condition is 0.7 per 100,000 and it affects both women and men (7, 8). It is characterised by intense, intermittent and sharp, unilateral pain in the base of the tongue, pharynx, tonsil area and/or at the mandibular angle, often radiating to the ipsilateral ear (9). The pain can be located both in front of and behind the ear (10). Glossopharyngeal neuralgia typically presents with brief pain episodes lasting seconds to a few minutes, but in some cases, aching pain can persist between neuralgia episodes (9–11). The pain can be triggered by chewing, swallowing, talking, yawning and coughing (9). This often leads to weight loss, as experienced by our patient (9, 12). When the condition involves virtually constant pain, with or without paroxysmal exacerbation, it is referred to as painful glossopharyngeal neuralgia. The clinical picture of our patient progressed from typical glossopharyngeal neuralgia to painful glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia can occur secondary to compression of the glossopharyngeal nerve from a tumour in the cerebellum/pons area, aneurysm, extracranial tumour in the oropharynx, elongation of the styloid processes (Eagle syndrome), dissection of the vertebral artery, tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess (9, 13). Eagle syndrome is caused by elongated styloid processes (> 30 mm) causing compression of nearby nerve structures, resulting in pain in the throat when swallowing, typically aggravated by neck rotation and lateral bending (6). In our patient, CT showed elongated styloid processes, but there were no signs of compression on the glossopharyngeal nerve. This, along with the absence of typical clinical findings, ruled out Eagle syndrome as the cause, and the elongated styloid process was interpreted as a normal variant. However, MRI revealed close proximity between the glossopharyngeal nerve and a blood vessel in the posterior cranial fossa, which is indicated as a common cause of glossopharyngeal neuralgia (9, 13).

In cases where medication is not effective, surgical options such as microvascular decompression or nerve section (neurotomy) may be considered (14). Microvascular decompression involves a microsurgical procedure in the posterior cranial fossa where the vein adjacent to the glossopharyngeal nerve is separated from surrounding structures, while neurotomy sacrifices nerve function to achieve pain relief (15). Alternatively, stereotactic radiosurgery with targeted radiation and destruction of the nerve may be effective, but this carries the risk of complications from radiation damage (15). Microvascular decompression is, however, the first choice in terms of neurosurgery. The procedure has a good pain-relieving effect, but a poorer prognosis has been reported in patients with venous compression of the nerve, as in our patient (16).

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia shares similarities with other pain conditions in the face and head. Trigeminal neuralgia is also characterised by paroxysmal pain episodes (17). Unlike glossopharyngeal neuralgia, patients with trigeminal neuralgia experience pain in the supply region of the trigeminal nerve (17, 18). The maxillary or mandibular nerves are typically affected (19). These conditions can usually be differentiated by the distribution of pain and whether, as in our patient, this is triggered by swallowing, which is typical for glossopharyngeal neuralgia (18). The patient in our case study stated that talking and chewing were particularly painful, which can also occur in TMD (20). Studies have reported the presence of at least one sign of TMD in 40–75 % of adults in the general population (21). Classic symptoms of this condition include clicking or popping sounds from the temporomandibular joint, pain in this joint or masticatory muscles when opening wide, chewing or moving the joint, and varying degrees of trismus. Due to the close anatomical proximity of the temporomandibular joint to the ear, a large proportion of patients with TMD experience symptoms in the ear, such as pain, tinnitus and a sensation of pressure (22, 23). This condition thus has overlapping symptoms with glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Our case study shows that glossopharyngeal neuralgia can cause significant distress and reduced quality of life. It is important that doctors and dentists are aware of this condition so that investigation and treatment can be initiated promptly.

The patient has consented to publication of this article.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 2.

Døving M, Handal T, Galteland P. Bakterielle odontogene infeksjoner. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2020; 140. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.19.0778. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Ghurye S, McMillan R. Orofacial pain - an update on diagnosis and management. Br Dent J 2017; 223: 639–47. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Hernández-Nuño de la Rosa MF, Keith DA, Siegel NS et al. Is there an association between otologic symptoms and temporomandibular disorders?: An evidence-based review. J Am Dent Assoc 2022; 153: 1096–103. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Porto De Toledo I, Stefani FM, Porporatti AL et al. Prevalence of otologic signs and symptoms in adult patients with temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2017; 21: 597–605. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

Arntzen KG, Slowinska PD, Odeh F. Forkalkning i kjeveligament. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2018; 138. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.17.0923. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Katusic S, Williams DB, Beard CM et al. Incidence and clinical features of glossopharyngeal neuralgia, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945-1984. Neuroepidemiology 1991; 10: 266–75. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Bruyn GW. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Cephalalgia 1983; 3: 143–57. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1–211.

- 10.

Chawla JC, Falconer MA. Glossopharyngeal and vagal neuralgia. BMJ 1967; 3: 529–31. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Blumenfeld A, Nikolskaya G. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2013; 17: 343. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Amthor KF, Eide PK. Glossopharyngeusnevralgi. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2003; 123: 3381–3. [PubMed]

- 13.

Chen J, Sindou M. Vago-glossopharyngeal neuralgia: a literature review of neurosurgical experience. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2015; 157: 311–21, discussion 321. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Lu VM, Goyal A, Graffeo CS et al. Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia Treatment Outcomes After Nerve Section, Microvascular Decompression, or Stereotactic Radiosurgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2018; 120: 572–582.e7. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Pollock BE, Boes CJ. Stereotactic radiosurgery for glossopharyngeal neuralgia: preliminary report of 5 cases. J Neurosurg 2011; 115: 936–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Zheng W, Zhao P, Song H et al. Prognostic factors for long-term outcomes of microvascular decompression in the treatment of glossopharyngeal neuralgia: a retrospective analysis of 97 patients. J Neurosurg 2021; 137: 1–8. [PubMed]

- 17.

Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. BMJ 2014; 348 (feb17 9): g474. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 18.

Teixeira MJ, de Siqueira SRDT, Bor-Seng-Shu E. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia: neurosurgical treatment and differential diagnosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008; 150: 471–5, discussion 475. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 19.

Bennetto L, Patel NK, Fuller G. Trigeminal neuralgia and its management. BMJ 2007; 334: 201–5. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Khan M, Nishi SE, Hassan SN et al. Trigeminal Neuralgia, Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia, and Myofascial Pain Dysfunction Syndrome: An Update. Pain Res Manag 2017; 2017. doi: 10.1155/2017/7438326. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 21.

Scrivani SJ, Keith DA, Kaban LB. Temporomandibular disorders. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 2693–705. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 22.

Kusdra PM, Stechman-Neto J, Leão BLC et al. Relationship between Otological Symptoms and TMD. Int Tinnitus J 2018; 22: 30–4. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Tuz HH, Onder EM, Kisnisci RS. Prevalence of otologic complaints in patients with temporomandibular disorder. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 123: 620–3. [PubMed][CrossRef]