MAIN FINDINGS

Mini-gastric bypass yielded comparable results to other established methods for bariatric surgery in Norway, as highlighted by national quality indicators.

The study showed an average total weight loss of 33.1 % following mini-gastric bypass.

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes decreased from 38.3 % to 8.8 %, and the prevalence of dyslipidaemia decreased from 84.8 % to 44.0 % two years post-surgery.

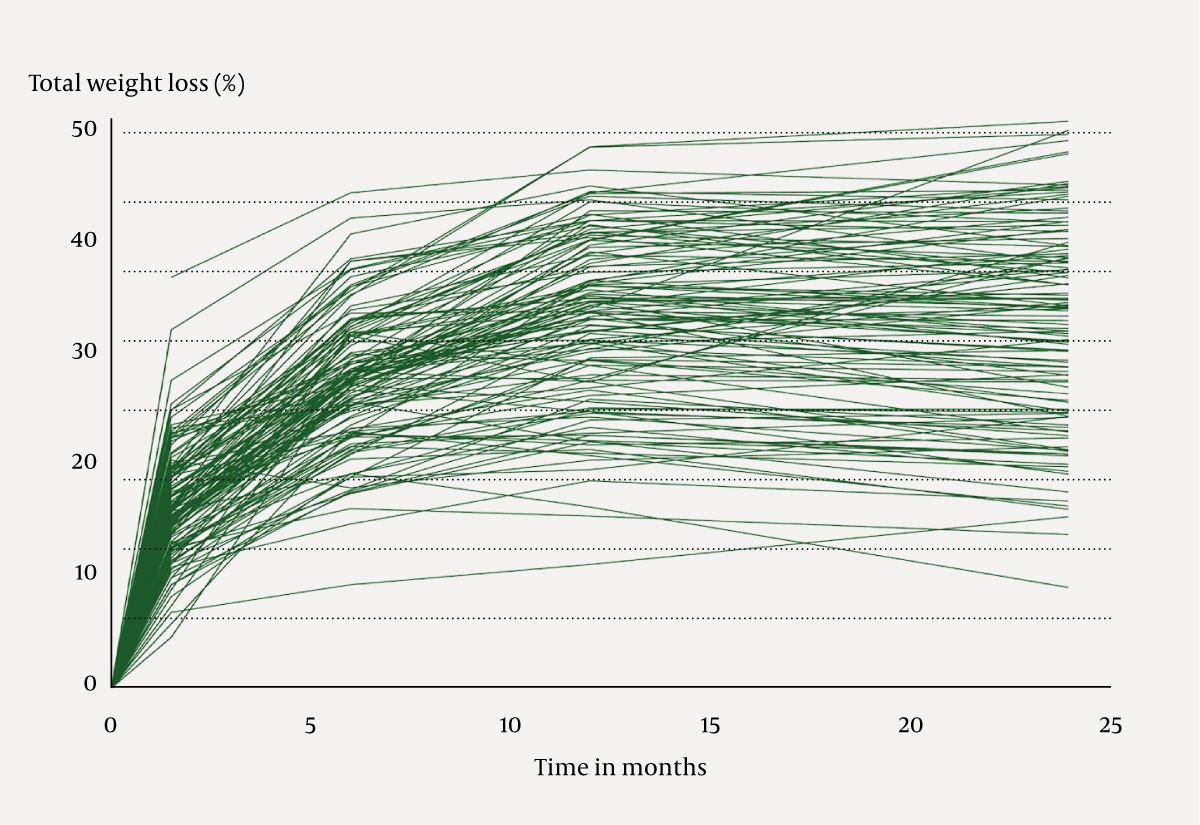

There were large individual variations in total weight loss (10–50 %) post-surgery.

Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2 and is a global health challenge (1). In Norway, the prevalence of obesity in adults increased from 8 % for men and 13 % for women in 1984 to 25 % and 20 % respectively in 2019. The prevalence of overweight and obesity in Norwegian children under the age of nine is 15–20 % (2).

Obesity increases the risk of conditions such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnoea and cardiovascular disease. It also increases the risk of musculoskeletal disorders, certain types of cancer, depression and reduced quality of life. Obesity is a chronic condition that can be prevented and treated through interdisciplinary efforts. Therapeutic lifestyle and dietary changes are first-line treatments. New medications such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues show promise for weight reduction. For some, bariatric surgery can lead to rapid, effective and long-term weight loss, with a beneficial effect on secondary comorbidity.

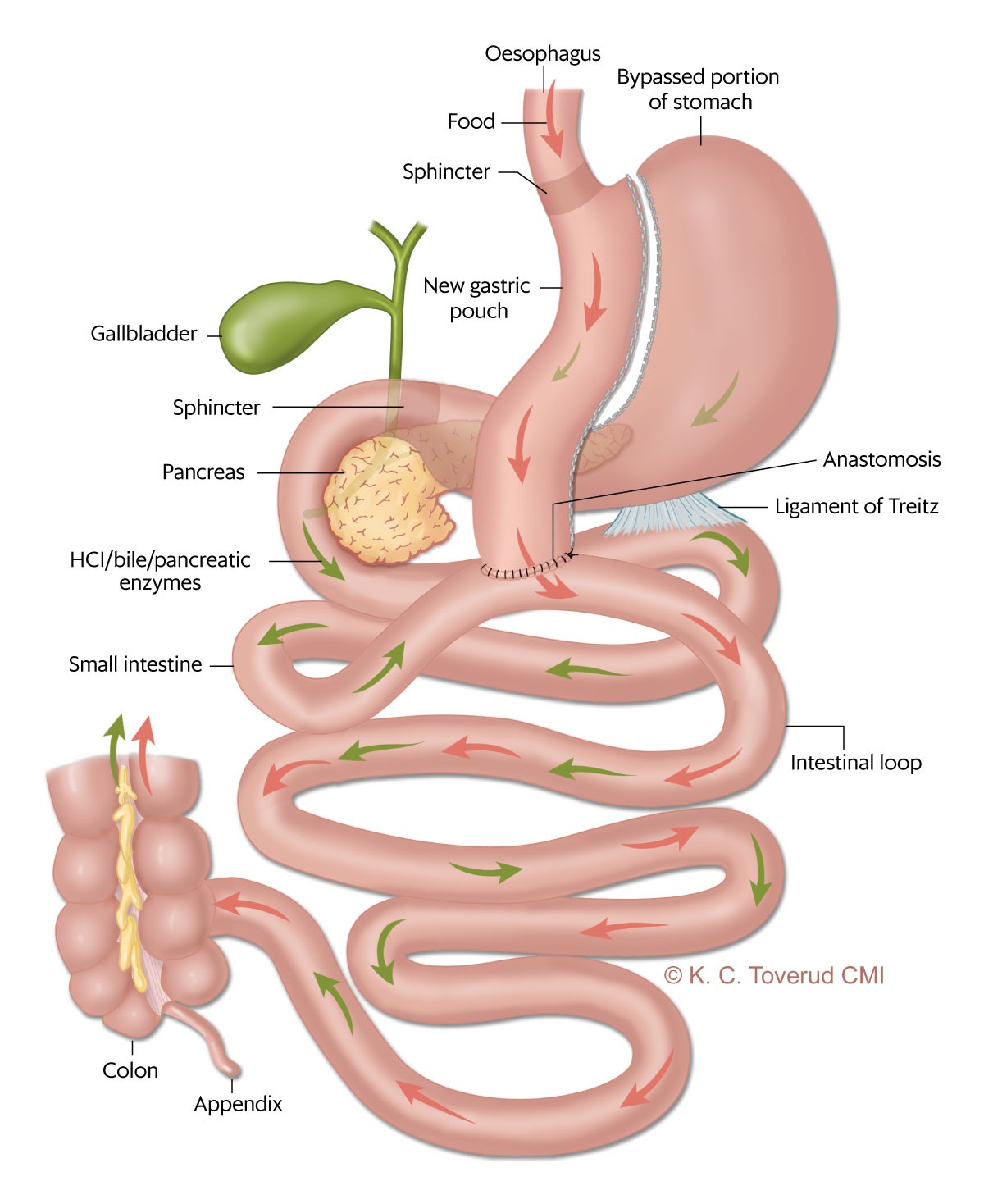

In Norway, approximately 2,900 bariatric surgery procedures are performed annually (3). The most common methods are longitudinal gastrectomy (gastric sleeve) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (4). Single anastomosis gastric bypass – also called mini-gastric bypass – is an alternative method that was first performed in 1997 in the United States (Figure 1) (5). Today, this is the third most common bariatric procedure globally (4).

In 2021, around 8–9 % of the operations registered in the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry Norway (SOReg-N) were mini-gastric bypass procedures (6). The method may have advantages related to technical aspects and the fact that only one anastomosis is necessary, which may reduce the risk of internal herniation and postoperative abdominal pain (7). Internal herniation is a potentially serious and not uncommon event after gastric bypass (8). Weight loss and improvement in metabolic diseases appear to be the same as after gastric bypass, both in meta-analyses and randomised trials (9, 10).

The aim of the study was to share our experiences with the introduction and use of mini-gastric bypass as a new method. These experiences may be valuable for other centres considering adopting this surgical method and for all those who treat this patient group.

Material and method

Patient population and design

The analysis takes the form of a retrospective quality assurance study. Bariatric surgery was first available at Oslo University Hospital in 2004 (11, 12), and the first mini-gastric bypass procedure (Figure 1) was performed in March 2016. The indication for mini-gastric bypass is BMI > 40 kg/m2 or BMI > 35 kg/m2 with an obesity-related secondary comorbidity.

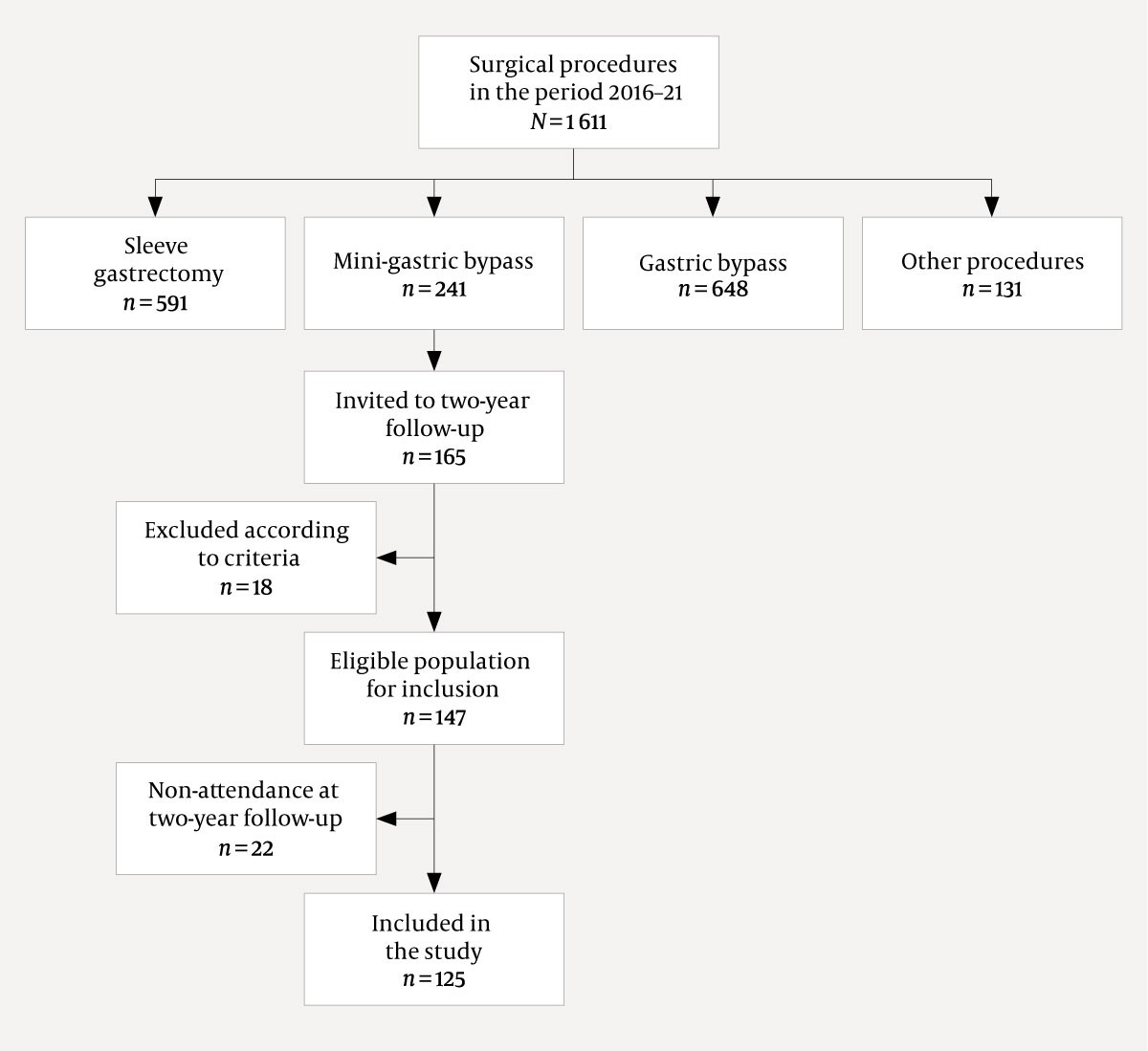

Patients who underwent mini-gastric bypass in the period 1 March 2016 to 1 April 2021 but had not previously had bariatric surgery, and were followed up post-surgery for two years or longer qualified for inclusion in the study. The data collection was completed in April 2021. A total of 241 patients underwent mini-gastric bypass during the period, and 147 of these met the inclusion criteria (Figure 2).

Patient data were entered in a quality register approved by the data protection officer at the hospital. The data included measurements for all quality indicators used in SOReg-N.

Definitions

Metabolic syndrome is classified according to the expert panel of the United States' National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) (13). Type 2 diabetes was defined as diabetes diagnosed at the time of referral by a general practitioner or hospital, with or without medication, or glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) > 6.5 % or 48 mmol/mol and/or use of diabetes medication. Remission of diabetes was defined as the absence of these criteria without medication.

Hypertension was classified as resting blood pressure > 140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medication. Dyslipidaemia was defined as LDL (low density lipoprotein) > 3.0 mmol/L, HDL (high density lipoprotein) < 1.0 mmol/L for men and < 1.3 mmol/L for women, and a triglyceride level > 1.7 mmol/L, a total cholesterol-HDL ratio > 5 and/or use of cholesterol-lowering medication.

Vitamin D deficiency was defined as 25 (OH) vitamin D3 < 50 nmol/L. Anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin level < 12 g/dl for women and < 13 g/dl for men and iron deficiency with a ferritin level < 15 μg/L (14).

Gastroesophageal reflux was defined as the use of acid-suppression medication or oesophagitis confirmed by gastroscopy. The patients were asked about chronic abdominal pain before and two years after mini-gastric bypass, defined as persistent and/or recurrent abdominal pain lasting three months or more. Postoperative complications were defined as early adverse postoperative events (< 30 days) and late events (> 30 days) according to the Clavien-Dindo classification of postoperative complications (15).

Total weight loss was defined as (weight at registration in database – weight at the two-year follow-up) / (weight at registration) × 100 %. We reported the results as numbers (percentages) and averages (standard deviation, SD).

Ethics

The health data have been collected and entered in a quality register with the approval of the data protection officer at Oslo University Hospital.

Surgical technique

All patients underwent laparoscopic surgery. A roughly 20 cm long tube was created, with the division of the stomach starting at the angular incisure and continuing up to near the gastroesophageal junction, with a 32 French nasogastric tube inserted for calibration. An anastomosis was created between the tube and the small intestine 170–200 cm from the ligament of Treitz (the intestinal loop from the ligament of Treitz to the anastomosis is called the biliopancreatic limb, Figure 1). The space between the transverse colon and the small intestine, which was lifted for anastomosis to the stomach, was closed.

Follow-up after mini-gastric bypass

The patients were checked by a clinical nutritionist, registered nurse or doctor at 6–8 weeks, six months, one year and two years after surgery. At the one-year and two-year follow-ups, secondary comorbidities and medication were recorded by a doctor. All patients were advised to take either a multivitamin, iron, calcium and vitamin D (perorally) as well as vitamin B12 (perorally or intramuscular injection) every three months, or daily peroral Baricol, which contains relevant minerals and vitamins. To reduce the risk of gallstones, 250 mg of peroral ursodeoxycholic acid twice daily was prescribed for six months post-surgery.

Results

Of the 147 patients invited to the two-year follow-up, 125 (85.0 %) attended. The average age was 47.4 (10.7) years, and 81/125 (64.8 %) were women. The average weight decreased from 134.4 (25.4) kg before surgery to 89.8 kg (19.8) two years after surgery. Total weight loss was 33.1 % (9.1). Individual weight development is shown in Figure 3. A comparison of the results in relation to the national quality indicators is shown in Table 1 (3, 6).

Table 1

Achievement of the quality indicators used in the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry Norway (SOReg-N) (6). The quality indicators for 125 patients who underwent mini-gastric bypass at Oslo University Hospital in the period 2016–20 are also shown. The figures from SOReg-N apply to all bariatric operations registered in 2020, with the exception of data with a follow-up period of two years, which apply to patients registered in 2019 (3).

| Quality indicators in SOReg-N | Mini-gastric bypass | SOReg-N |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients with hospital stay of less than three days (%) | 98 | 98 |

| Proportion of readmissions within 30 days of discharge (%) | 5 | 6 |

| Clavien-Dindo classification IIIb or more than 30 days (%) | 0 | 1 |

| Proportion of patients followed up for one year (%) | 90 | 85 |

| Proportion of patients followed up for two years (%) | 85 | 60–70 |

| Proportion of patients with total weight loss > 20 % after two years (%) | 94 | 90 |

The proportion of patients with type 2 diabetes before surgery and two years after surgery was 46/120 (38.3 %) and 11/125 (8.8 %), respectively. The criteria for dyslipidaemia were met in 106/125 (84.8 %) patients before surgery and in 55/125 (44.0 %) at the two-year follow-up (Table 2). Before surgery, 4/125 (3.2 %) patients reported chronic abdominal pain, while 14/125 (11.2 %) reported chronic abdominal pain two years after surgery. None of the patients with chronic abdominal pain after two years had reported this before surgery.

Table 2

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia in 125 patients before and two years after mini-gastric bypass for morbid obesity at Oslo University Hospital in the period 2016–20.

| Pre-surgery | Two years post-surgery | |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes type 2 | 46/120 (38.3 %) | 11/125 (8.8 %) |

| Hypertension | 90/121 (74.4 %) | 43/118 (36.4 %) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 106/125 (84.8 %) | 55/125 (44.0 %) |

The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux increased from 25/125 (20.0 %) pre-surgery to 34/125 (27.2 %) after mini-gastric bypass. Anaemia was observed in 13/108 (12 %) patients and iron deficiency in 7/111 (6.3 %) after two years. All of these patients were women. Vitamin D supplements were used by 117/122 (95.9 %) patients, and vitamin D deficiency was found in 25/108 (23.1 %) patients after two years.

Complications

Early complications were recorded in 6/125 (4.8 %) patients and late complications in 7/125 (5.6 %). No patients underwent reoperation within 30 days, and patient events were managed through observation or endoscopy (all had Clavien-Dindo complication grade IIIa or lower, Table 1). Two patients underwent reoperation more than 30 days after the first operation with an indication of internal herniation, and this was confirmed in one patient.

Discussion

Experiences with mini-gastric bypass at Oslo University Hospital demonstrate that the procedure can be performed with a low incidence of complications in the first two years. In the literature, a perioperative complication rate of 0–10 % is reported, with 0–2 % of the procedures being converted to open surgery (16). All operations at the centre were performed laparoscopically without conversion to laparotomy. None of the early complications (< 30 days) were severe, and it was possible to manage them without the need for anaesthesia or intensive care. The results are comparable with the national quality indicators for bariatric surgery in Norway. The experience with using other types of bariatric surgery at the hospital contributed to the safe introduction of mini-gastric bypass.

As observed in other studies of mini-gastric bypass, our study found a considerable average weight loss two years after surgery. This is comparable to the results after gastric bypass at our hospital (17). Not all of the mechanisms of weight loss after bariatric surgery are known, and there were substantial individual differences in weight loss (Figure 3). Limitations in food intake and malabsorption alone cannot fully explain the outcomes. The small intestine and adipose tissue are endocrine organs, and physiological processes that control weight and blood sugar are impacted by bariatric surgery (18, 19). Gaining a deeper insight into the factors that contribute to the significant variation in weight development could play a crucial role in tailoring individualised treatment strategies.

We observed normalisation of plasma glucose in 77 % of patients with type 2 diabetes two years after surgery. This corresponds to findings from other studies following mini-gastric bypass and gastric bypass. In the well-known randomised YOMEGA trial (omega loop versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass), comparisons of these two surgical procedures showed no difference in type 2 diabetes remission (9). The prevalence of hypertension and dyslipidaemia in our material was approximately halved after mini-gastric bypass. Few patients had anaemia and iron deficiency, but a relatively large proportion (23 %) had vitamin D deficiency. This may be due to suboptimal substitution and/or greater malabsorption than expected. Longer-term results are needed to further analyse this. In the YOMEGA trial, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency after mini-gastric bypass (17.4 %) and gastric bypass (25.3 %). The trial also showed that 21.4 % of patients who underwent mini-gastric bypass with 200 cm of biliopancreatic limb developed nutritional problems. None of our patients required revision surgery, and none were found to have severe deficiencies requiring treatment.

We observed an increase in the proportion of patients who used acid-suppression medication after mini-gastric bypass or who were diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease by endoscopy. This was despite weight loss, which can reduce reflux. In the YOMEGA trial, gastroscopy two years post-surgery showed that 5.6 % (mini-gastric bypass) and 1.4 % (gastric bypass) had gastroesophageal reflux disease, respectively. A gastric pouch shorter than 9 cm is correlated with an increased incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (20).

Our study showed an increased incidence of patient-reported chronic abdominal pain after mini-gastric bypass (11.1 %), but this was lower than was observed after gastric bypass (21, 22). However, a questionnaire was used to map chronic abdominal pain after other bariatric surgical procedures, while patients who underwent mini-gastric bypass were asked a simple 'Yes/No' question about abdominal pain in the last three months. The figures are therefore not directly comparable. In the YOMEGA trial, there were 24/117 (20 %) readmissions after gastric bypass, and abdominal pain was the reason in 5/24 (21 %) patients.

It is assumed that fewer patients will develop internal herniation after mini-gastric bypass than after gastric bypass. The condition has been reported in up to 10 % of patients after gastric bypass (23). The absence of entero-entero anastomosis in mini-gastric bypass may also contribute to a reduced incidence of abdominal pain (24).

Long-term follow-up after mini-gastric bypass shows a low (< 4 %) prevalence of internal herniation, which is significantly lower than after gastric bypass (7,10).

The risks and consequences associated with bile reflux through the anastomosis between the stomach and the small intestine after mini-gastric bypass are hotly debated and unclear (Figure 1). Controversies persist about whether bile reflux can predispose to malignancy (25).

Bile reflux can necessitate reoperation and conversion to gastric bypass (26).

There is no general consensus on which bariatric surgery method should be used for individual patients. We prefer mini-gastric bypass or gastric bypass for patients with metabolic disease and gastric bypass for patients with esophagitis or Barrett's oesophagus. It is possible that the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease would have been lower after mini-gastric bypass if we had excluded patients taking acid-suppression medication prior to the operation. For patients who do not have a metabolic disorder or gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, we perform longitudinal gastrectomy, especially in women of childbearing age with a desire to have children (27–29).

Mini-gastric bypass is the first-line surgical procedure for morbid obesity, but it is also used in revisional surgery after longitudinal gastrectomy and for patients with unsatisfactory weight loss. In the future, weight-loss medications are likely to be the preferred first-line approach for unsatisfactory weight development after bariatric surgery, as opposed to further surgery.

The study is retrospective, and more detailed mapping of chronic abdominal pain in longitudinal studies is needed. Fifteen per cent of the patients did not attend the two-year follow-up, which may represent a patient population bias. However, compared to the national quality indicator for bariatric surgery, where the two-year follow-up attendance rate in 2020 was approximately 60 - 70 %, this is still better than expected. Nonetheless, the non-attendance of some patients does introduce limitations to the interpretation of results. Patient selection for mini-gastric bypass will vary between different centres and may have impacted on the findings.

Conclusion

Our early experiences with mini-gastric bypass show promising results regarding weight development. The incidence of complications is comparable to that following other bariatric surgical procedures. Mini-gastric bypass has beneficial effects on several secondary comorbidities up to two years after surgery. Long-term outcome mapping is needed to determine this method's role in the treatment algorithm for patients with morbid obesity.

The article is based on a student paper by the first author at the University of Oslo.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Rechel B. The role of public health organizations in addressing public health problems in Europe: the case of obesity, alcohol and antimicrobial resistance. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2018.

- 2.

Erik R. Sund VR, Krokstad S. Folkehelseutfordringer i Trøndelag. Folkehelsepolitisk rapport med helsestatistikk fra HUNT inkludert tall fra HUNT4 (2017-19). https://www.ntnu.no/documents/10304/1269212242/Folkehelseutfordringer+i+Tr%C3%B8ndelag+2019.pdf/153c78b4-ad78-4b5a-a65b-2c1b9ff1252b Accessed 31.8.2023.

- 3.

SOReg. Norsk kvalitetsregister for fedmekirurgi (SOReg): Årsrapport for 2019 med plan om forbedringstiltak. https://helsebergen.no/seksjon/soreg/Documents/%C3%85rsrapport%202019%20-%20Soreg%20N.pdf Accessed 31.8.2023.

- 4.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P et al. Bariatric Surgery Survey 2018: Similarities and Disparities Among the 5 IFSO Chapters. Obes Surg 2021; 31: 1937–48. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Rutledge R, Kular K, Manchanda N. The Mini-Gastric Bypass original technique. Int J Surg 2019; 61: 38–41. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

SOReg. Norsk kvalitetsregister for fedmekirurgi (SOReg):Årsrapport for 2021 med plan om forbedringstiltak. https://www.kvalitetsregistre.no/sites/default/files/2022-06/%C3%85rsrapport%202021%20SOReg-N.pdf Accessed 31.8.2023.

- 7.

Lee WJ, Ser KH, Lee YC et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y vs. mini-gastric bypass for the treatment of morbid obesity: a 10-year experience. Obes Surg 2012; 22: 1827–34. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Mala T, Kristinsson J. Akutt inneklemming av tarm etter gastrisk bypass for sykelig fedme. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2013; 133: 640–4. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Robert M, Espalieu P, Pelascini E et al. Efficacy and safety of one anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for obesity (YOMEGA): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2019; 393: 1299–309. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Liagre A, Benois M, Queralto M et al. Ten-year outcome of one-anastomosis gastric bypass with a biliopancreatic limb of 150 cm versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a single-institution series of 940 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2022; 18: 1228–38. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Salte OB, Søvik TT, Risstad H et al. Fedmekirurgi ved Oslo universitetssykehus 2004–14. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2019; 139: 921–6. [CrossRef]

- 12.

Chahal-Kummen M, Salte OBK, Hewitt S et al. Health benefits and risks during 10 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 2020; 34: 5368–76. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CNB et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the national cholesterol education program adult treatment panel III guidelines. Circulation 2004; 110: 227–39. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Chaparro CM, Suchdev PS. Anemia epidemiology, pathophysiology, and etiology in low- and middle-income countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2019; 1450: 15–31. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 187–96. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Georgiadou D, Sergentanis TN, Nixon A et al. Efficacy and safety of laparoscopic mini gastric bypass. A systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014; 10: 984–91. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 17.

Søvik TT, Irandoust B, Birkeland KI et al. Type 2-diabetes og metabolsk syndrom før og etter gastrisk bypass. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2010; 130: 1347–50. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 18.

Akalestou E, Miras AD, Rutter GA et al. Mechanisms of Weight Loss After Obesity Surgery. Endocr Rev 2022; 43: 19–34. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 19.

Miras AD, le Roux CW. Mechanisms underlying weight loss after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10: 575–84. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Musella M, Susa A, Manno E et al. Complications Following the Mini/One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass (MGB/OAGB): a Multi-institutional Survey on 2678 Patients with a Mid-term (5 Years) Follow-up. Obes Surg 2017; 27: 2956–67. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 21.

Chahal-Kummen M, Blom-Høgestøl IK, Eribe I et al. Abdominal pain and symptoms before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. BJS Open 2019; 3: 317–26. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 22.

Chahal-Kummen M, Nordahl M, Våge V et al. A prospective longitudinal study of chronic abdominal pain and symptoms after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2021; 17: 2054–64. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Geubbels N, Lijftogt N, Fiocco M et al. Meta-analysis of internal herniation after gastric bypass surgery. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 451–60. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 24.

Hedberg S, Xiao Y, Klasson A et al. The Jejunojejunostomy: an Achilles Heel of the Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Construction. Obes Surg 2021; 31: 5141–7. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 25.

Mahawar KK, Carr WR, Balupuri S et al. Controversy surrounding 'mini' gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2014; 24: 324–33. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 26.

Saarinen T, Räsänen J, Salo J et al. Bile Reflux Scintigraphy After Mini-Gastric Bypass. Obes Surg 2017; 27: 2083–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 27.

Renault K, Gyrtrup HJ, Damgaard K et al. Pregnant woman with fatal complication after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012; 91: 873–5. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 28.

Dave DM, Clarke KO, Manicone JA et al. Internal hernias in pregnant females with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2019; 15: 1633–40. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 29.

Gonzalez-Urquijo M, Zambrano-Lara M, Patiño-Gallegos JA et al. Pregnant patients with internal hernia after gastric bypass: a single-center experience. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2021; 17: 1344–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]