MAIN FINDINGS

Treatment with COVID-19 convalescent plasma in 79 patients was well tolerated, and apart from a skin reaction in two of the patients, no serious adverse effects were reported.

Twenty of the 59 patients with an underlying immunodeficiency died in hospital, while 11 of the 20 patients assumed to be immunocompetent died.

COVID-19 convalescent plasma (NORPLASMA) (1) first became available to Norwegian patients in the spring of 2020. The Norwegian Directorate of Health recommended use of the product in patients who were at risk of developing a severe/life-threatening course of COVID-19, where the attending doctor believed there could be clinical benefits for the patient (2). It was also decided to include patients receiving plasma in the observational study NORPLASMA MONITOR (2), but it was not possible to conduct a randomised clinical trial (3).

All Norwegian hospitals initially conducted clinical studies of COVID-19 patients (4), parallel to inclusion in the observational study Norwegian SARS-CoV-2 (a cohort study), where patients received standard treatment according to consensus-based guidelines. Before 7 December 2020, a small number of patients with an expected severe course of infection were offered experimental treatment with convalescent plasma (5). We have previously discussed the changes in indications for convalescent plasma treatment (3). In the subsequent period (7 December 2020–30 March 2022), treatment with convalescent plasma was limited to critically ill COVID-19 patients where the underlying disease or immunosuppressive treatment was thought to inhibit the immune system/vaccine response. Here we describe the clinical characteristics, comorbidity and mortality in patients who received convalescent plasma at 15 Norwegian hospitals/nursing homes during these two periods.

Material and method

NORPLASMA MONITOR is an observational study in which the aim is to collect data from patients who have received COVID-19 convalescent plasma. The protocol, information/consent form and reporting form for patient data collection (REK South-East A, 148622; NCT04463823) are described on the project's website (6). The data protection officers at participating healthcare authorities approved study participation.

In autumn 2020, the MONITOR study joined forces with the Norwegian SARS-CoV-2 cohort study (REK number 106624; NCT04381819) in a collaboration involving patients recruited at Oslo University Hospital (OUS) and the hospitals in Vestre Viken Hospital Trust. From a total of 15 participating hospitals and nursing homes, 79 patients who had received convalescent plasma were included either in the MONITOR study (n = 55) or via the Norwegian SARS-CoV-2 study (n = 24).

Fifty-eight patients/next of kin gave written informed consent for inclusion in one of the studies in connection with or after (but independently of) the plasma treatment. Twenty-one deceased patients were later included, after the consent requirement was waived for treated patients who died before inclusion (amendment notification to the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, approved 11 March 2022). Data from participating blood banks showed that 20–25 patients who had received convalescent plasma were not included in the study despite repeated enquiries to the attending doctor. The patients had either declined or had not been asked.

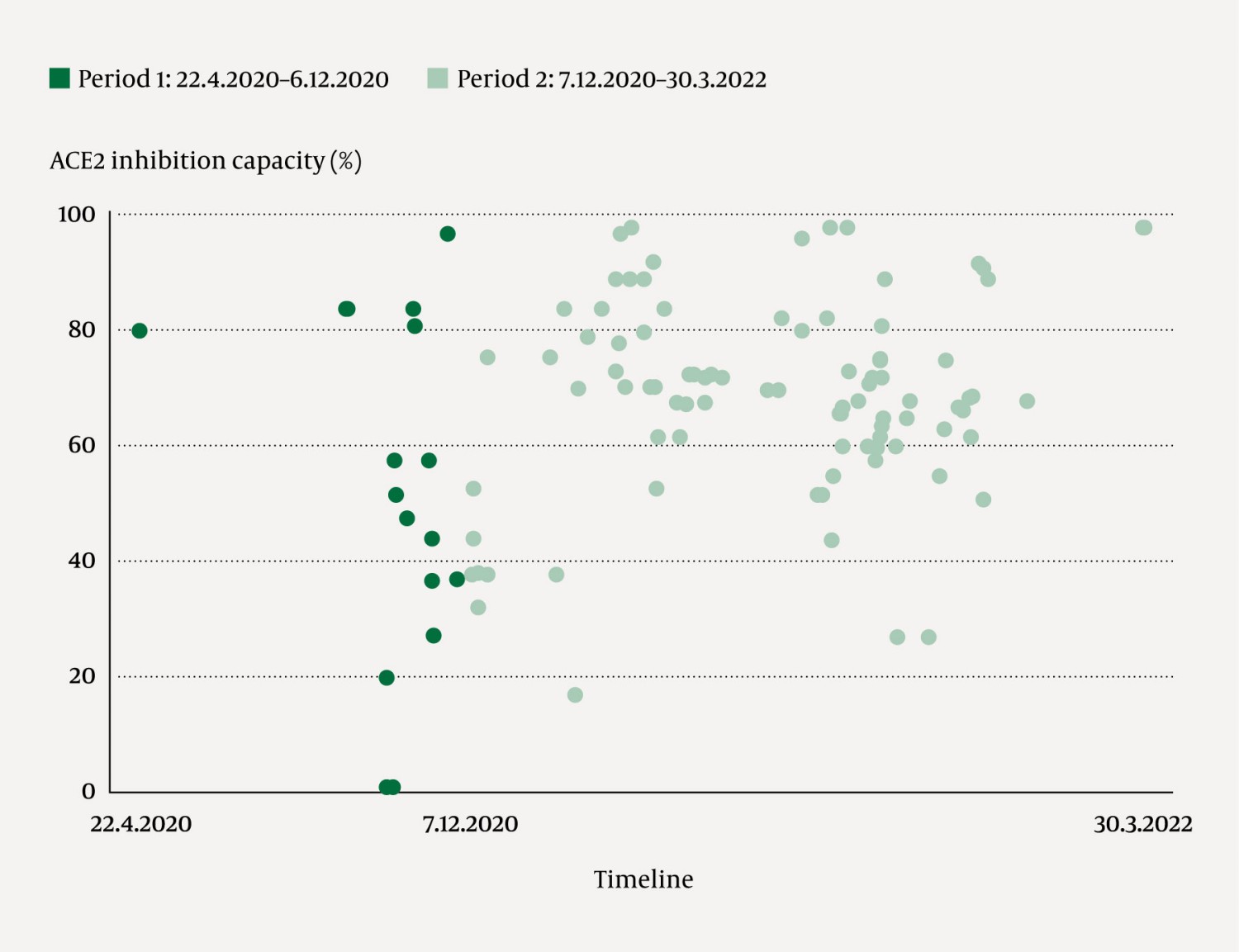

After separate consent for experimental treatment was obtained, 1–2 units of ABO-compatible COVID-19 convalescent plasma were ordered (1). Some patients received repeated treatments, and a total of 193 plasma units were transfused; 26 in period 1 (22 April 2020–6 December 2020) and 167 in period 2 (7 December 2020–30 March 2022). Antibody content, calculated as the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) inhibition capacity (1, 3), was measured for 172/193 plasma units (Figure 1). In total, 46 transfused units had an ACE2 inhibition capacity of less than 60 %, either because they were administered early in the pandemic (3) or because they were rare blood types AB or B.

Collection and storage of patient data

Health information, including immune status, results of blood tests, vital parameters (respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation and temperature), treatment and course of infection was obtained from patient records and laboratory data systems according to the protocol (6). It was then de-identified and registered in the project database Ledidi PRJCTS® (Ledidi.com, Oslo). Data from the Norwegian SARS-CoV-2 study were collected from the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) online database using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), version 8.11.11 (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), which is administered by the University of Oxford.

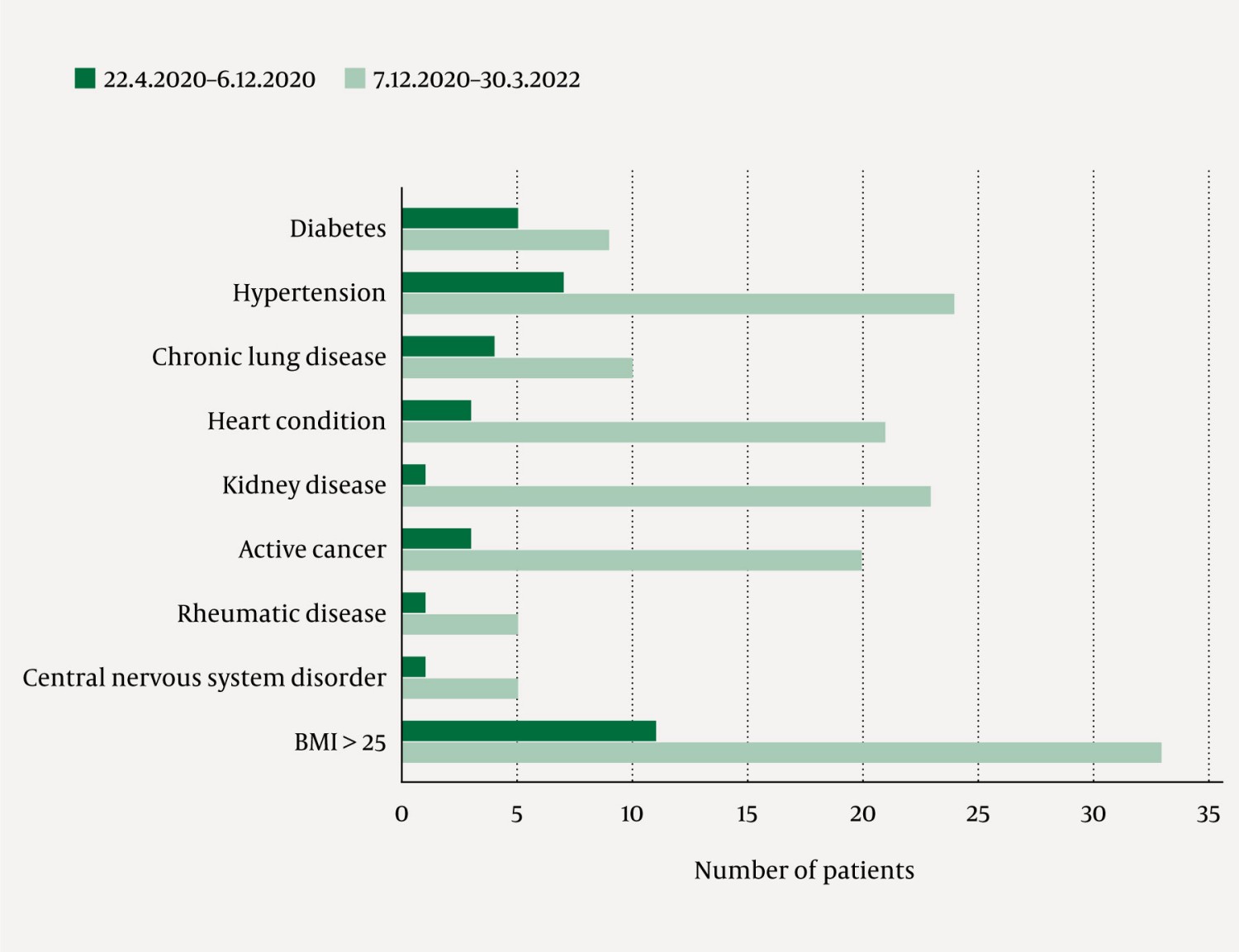

A comorbidity score was created for all patients by adding the sum of risk factors documented in the patient journal, based on the following list adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (7): diabetes, hypertension, heart condition, chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease, active cancer, rheumatic disease, disease of the central nervous system and body mass index (BMI) > 25 (Figure 2). Patients defined as immunosuppressed have primary or secondary immunodeficiency or receive immunomodulatory treatment. Storage and handling of personal data followed approved procedures at Oslo University Hospital.

The data were processed in Microsoft Excel 2016. Normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test) was tested in GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1. Continuous data were predominantly non-parametric and are reported as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise specified.

Results

The study included 79 COVID-19 patients, 51 of whom were men, treated with convalescent plasma in the period 22 April 2020–30 March 2022. The median age was 65 years (51–73). The patients received a median of two (min–max 1–21) units of convalescent plasma.

A total of 59 patients had immunodeficiency. This was due to immunomodulatory treatment after transplantation, cancer of the blood/immune system or cancer treatment in 38 patients. Patients with immunodeficiency were younger (63 years (46–70)) than those assumed to be immunocompetent (73 years (63–81)). Of the 59 patients with immunodeficiency, 20 died in hospital, compared to 11 out of 20 immunocompetent patients (Table 1).

Table 1

Demographic/clinical data for 79 patients who received COVID-19 convalescent plasma in the period 22 April 2020–30 March 2022. 'Immunosuppressed' is defined as patients with primary/secondary immunodeficiency or those receiving immunomodulatory treatment. Number/median with interquartile range is shown in brackets unless otherwise specified.

| Variable | Immunosuppressed | Immunocompetent | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 59 | 20 | 79 | |

| No. of men | 37 | 14 | 51 | |

| Age | 63 (46 - 70) | 73 (63–81) | 65 (51–73) | |

| Comorbidity score1 (0–9) | 3 (2 - 4) | 1.5 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | |

| BMI2 (mean ± SD) | 27.6 ± 4.3 | 30.7 ± 5.3 | 28.7 ± 4.9 | |

| No. of patients receiving intensive care | 25 | 11 | 36 | |

| Pre-treatment vital parameters: | ||||

|

| Respiratory rate | 21 (18–28) | 23 (20–31) | 21,5 (16–28) |

|

| Heart rate | 81 (74–96) | 83 (66–91) | 81 (70–95) |

|

| Oxygen saturation (SaO2) | 93 (91–96) | 95 (92–96) | 94 (91–96) |

|

| Temperature (oC) (mean ± SD) | 37.8 ± 1.0 | 37.4 ± 0.8 | 37.7 ± 0.9 |

| Antibody analysis (n = 50 patients): | ||||

|

| Positive anti-SARS-CoV-2 | 7 | 6 | 13 |

|

| Negative anti-SARS-CoV-2 | 31 | 6 | 37 |

| Course: | ||||

|

| Days from positive test to admission | 4 (0–8) | 0 (0–3) | 2 (0–6) |

|

| Days from positive test to plasma | 7 (3–16) | 3 (1–6) | 6 (2–13) |

|

| Days in hospital after plasma | 11 (5–20) | 10 (3–24) | 10 (4–20) |

|

| Days in hospital | 16 (11–30) | 12 (7–24) | 16 (9–30) |

|

| No. who died in hospital | 20 | 11 | 31 |

| Convalescent plasma transfused: | ||||

|

| Units of plasma transfused per patient | 2 (2–3) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) |

|

| ACE2 inhibition capacity, % | 70 (62–80) | 60 (48–80) | 68 (60–80) |

|

| No. of transfused units analysed for ACE2 inhibition capacity | 143 | 29 | 172 |

1Comorbidity score 0–9: sum of comorbidities per patient for the following: diabetes, hypertension, heart condition, chronic lung disease, kidney disease, active cancer, rheumatic disease, central nervous system disorder, body mass index > 25.

2Body mass index: n = 47 (30 immunosuppressed and 17 immunocompetent)

The patients had a median of two (1–4) comorbidities. The number of patients with each condition included in the calculation of the comorbidity score is shown in Figure 2. Immunocompromised patients had a median of three (2–4) comorbidities, compared to 1.5 (1–3) among the immunocompetent patients. The proportion of patients with heart, kidney or cancer diseases appeared to increase from period 1 to period 2.

In 21/26 units of convalescent plasma given to 14 patients in period 1, the median ACE2 inhibition capacity was later measured at 48 % (37–83). In period 2, 65 patients received plasma with a median ACE2 inhibition capacity of 70 % (62–80, measured in 151/167 plasma units (Figure 1)). In 50/79 patients, antibody levels against SARS-CoV-2 were measured before they received transfused plasma: 37/50 had no detectable antibodies, and among the 24 who survived the hospital stay, 22 had immunodeficiency. Of the 13 patients with a positive antibody test, 8 survived, and 6 of these had immunodeficiency (further details can be provided upon request to the corresponding author).

Two patients experienced allergic skin reactions (rash/itchiness) attributed to the plasma treatment, otherwise no adverse effects were reported.

Discussion

Convalescent plasma was administered in Norway as an experimental treatment for critically ill COVID-19 patients from 2020 to 2022. This was eventually restricted to critically ill patients with immunodeficiency.

In our dataset, we found a total mortality of 39 %, which is significantly higher than overall COVID-19 mortality at Norwegian hospitals (4). Figures from the Norwegian Intensive Care and Pandemic Register show a national mortality rate of 6 % among patients hospitalised with COVID-19 in the same period (NIPaR, case number 2022/10466). The high mortality may be due to the strict indication criteria and the fact that it was the most severely ill patients who were included, given the lack of other available treatment options. In international studies, convalescent plasma did not lead to increased mortality (8).

The lower mortality among patients with immunodeficiency can be explained by the younger age of this patient population compared with the group assumed to be immunocompetent. As at-risk patients started to be identified at an earlier stage, treatment with convalescent plasma could be administered earlier in the course of infection. The ACE2 inhibition capacity in convalescent plasma was generally higher in period 2.

Convalescent plasma has few adverse effects and is considered safe (8). Possible efficacy in immunocompromised patients is supported by a recently published randomised clinical trial (9). The patient group (n = 50) that underwent SARS-CoV-2 antibody measurement before plasma treatment was too small to analyse the significance of antibody response following previous infection/vaccine. In Norway, the number of patients who received plasma treatment was low. This limited dataset must therefore be interpreted with caution. The fact that it was not possible to carry out a randomised clinical trial is a weakness of the study (3). Nonetheless, our main finding is that convalescent plasma appears to be safe and can be considered for the treatment of COVID-19 patients with immunodeficiency.

We would like to extend our thanks to Tine Nyberg, Helle B. Hager, Lars Thoresen, Eli Leirdal Hoem, Ingrid Hoff, Aleksander Rygh Holten, Diana Mikova and everyone who contributed to the collection of patient data. We would also like to thank the patients who participated.

This article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Nissen-Meyer LSH, Steinsvåg TT, Fenstad MH et al. Rekonvalesensplasma mot covid-19 fremstilt fra norske blodgivere. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2023; 143. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.22.0180. [CrossRef]

- 2.

Helsedirektoratet. Informasjon om tilgang på rekonvalesentplasma for bruk ved behandling. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/tema/blodgivning-og-transfusjonsmedisin/tilgang-til-rekonvalesensplasma-for-behandling-av-covid-19/Informasjon%20om%20tilgang%20p%C3%A5%20rekonvalesentplasma%20for%20bruk%20ved%20behandling.pdf/_/attachment/inline/c3056b55e4d3-44a9-900e-bd799e80f31e:8bb59cef75c786ea957a5565b19da58fc7f9bdf3/Informasjon%20om%20tilgang%20p%C3%A5%20rekonvalesentplasma%20for%20bruk%20ved%20behandling.pdf Accessed 2.4.2022.

- 3.

Nissen-Meyer LSH, Hervig T, Fevang B et al. Covid-19-rekonvalesensplasma fra norske blodgivere. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2022; 142: 768–70.

- 4.

Barratt-Due A, Olsen IC, Nezvalova-Henriksen K et al. Evaluation of the Effects of Remdesivir and Hydroxychloroquine on Viral Clearance in COVID-19 : A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174: 1261–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Hahn M, Condori MEH, Totland A et al. Pasient med alvorlig covid-19 behandlet med rekonvalesensplasma. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2020; 140: 1261–3. [CrossRef]

- 6.

OUS. NORPLASMA Monitor. https://www.ous-research.no/home/norplasma/Monitor/21134 Accessed 19.8.2022.

- 7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying Medical Conditions Associated with Higher Risk for Severe COVID-19: Information for Healthcare Professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html Accessed 16.1.2023.

- 8.

Joyner MJ, Bruno KA, Klassen SA et al. Safety Update: COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma in 20,000 Hospitalized Patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2020; 95: 1888–97. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Denkinger CM, Janssen M, Schäkel U et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody-containing plasma improves outcome in patients with hematologic or solid cancer and severe COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. Nat Cancer 2023; 4: 96–107. [PubMed]