Metastatic thymoma is a rare and serious condition that is treated with cytostatics according to the guidelines. Cytostatics have limited efficacy and are toxic. This case report illustrates how glucocorticoid treatment can have a significant effect.

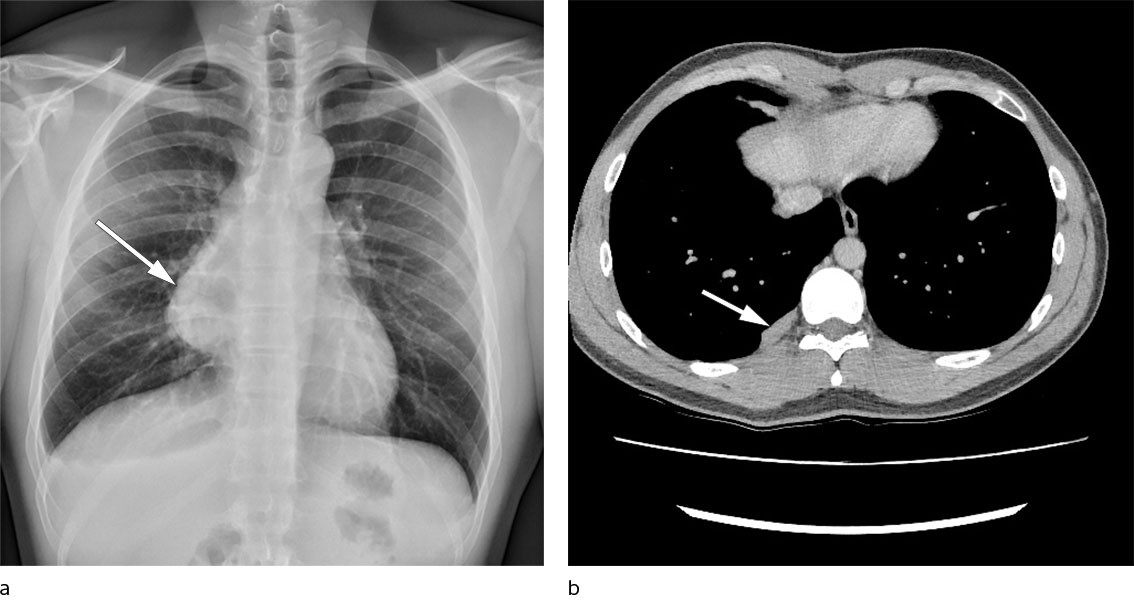

The patient, a man in his twenties, was a never-smoker with a history of childhood asthma but was otherwise previously healthy. The case history started with persistent chest pain and increasing dyspnoea on exertion following a minor trauma at the gym. Chest X-ray revealed a large new mediastinal mass on the right side compared with an X-ray taken four years previously in connection with a different trauma (Figure 1a). Chest CT revealed a tumour sized 12 × 9 × 6.5 cm in the anterior mediastinum, suspected of arising from residual thymic tissue, with no signs of invasion into mediastinal structures. A CT-guided biopsy was assessed to be type B1/B2 thymoma. The patient underwent radical surgery with sternotomy and thymectomy with no macroscopic residual tumour and no complications.

Histopathological examination of the resected tissue showed type B2 thymoma which had breached the capsule, with positive surgical margins. The extensive necrosis in the specimen was considered to be ischaemic changes.

The patient received postoperative radiotherapy. He was followed up every six months with chest CT and check-ups at the respiratory medicine outpatient clinic. Two years post-surgery, three new masses were detected in the right pleura (Figure 1b). The largest was 23 mm, and on imaging it resembled the original extirpated thymoma when compared to the preoperative chest CT. The pleural masses had moderately increased uptake of FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose) on PET-CT. A CT-guided pleural biopsy found hypocellular fibrosis and striated muscle tissue.

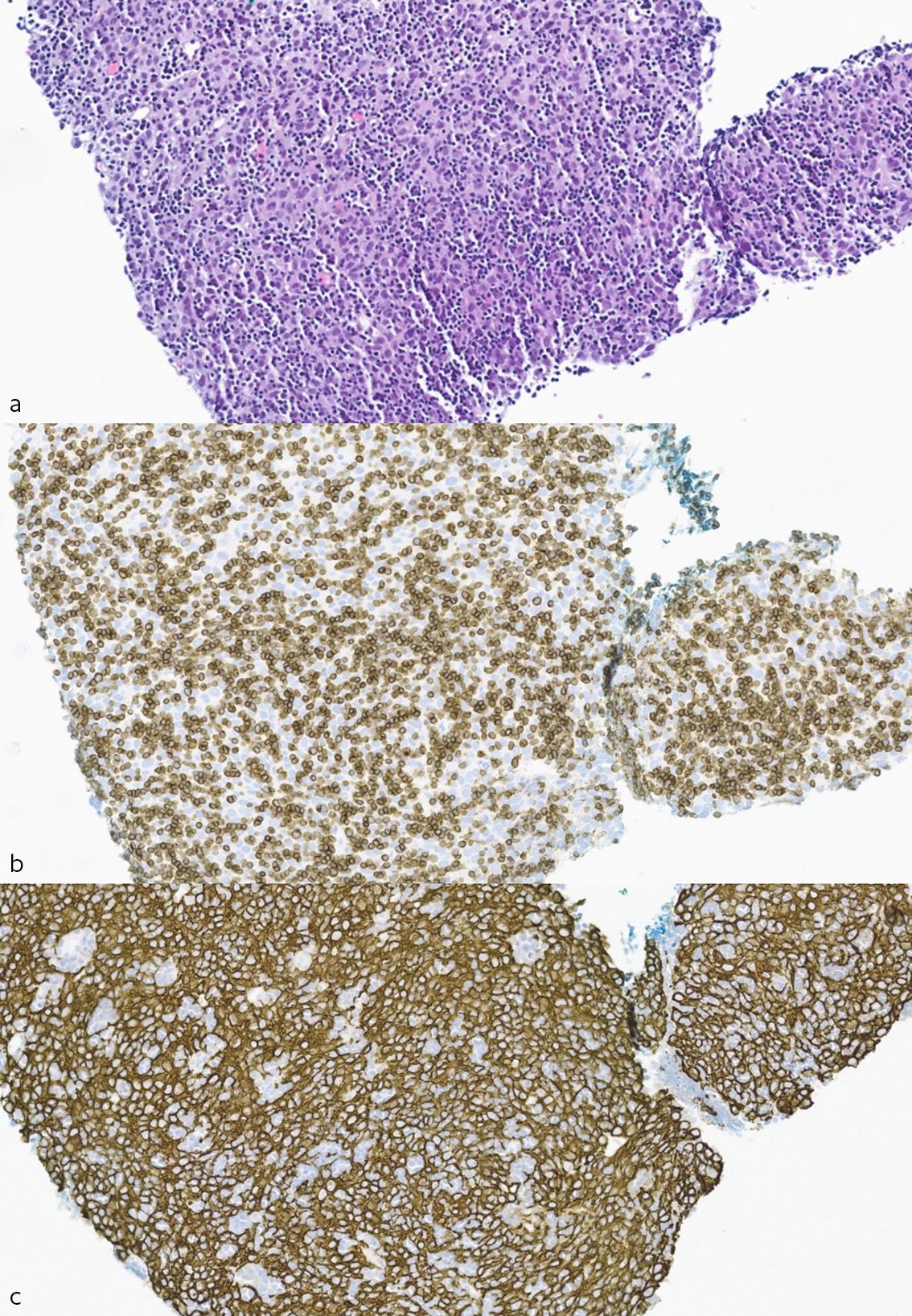

The patient was discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting at the university hospital, with the recommendation given for monitoring and treatment with cytostatics if metastases were confirmed. Chest CT six months later found that the largest mass had increased in size to 40 mm. Repeated CT-guided biopsy revealed hypercellular tumour tissue with diffuse growth consisting of a mix of neoplastic epithelial cells and immature T-lymphocytes (thymocytes), which was consistent with thymoma (Figure 2a–c). There were abundant T-lymphocytes and partly confluent sheets of epithelial cells, which is classed as type B2, and thus morphologically similar to the patient's primary thymoma.

The patient was offered treatment with cytostatics, but he did not want this due to the low expected antitumour effect and considerable cardiotoxicity. He undertook his own literature search and found publications about glucocorticoid treatment.

Since the literature did not give clear recommendations, the patient received three different treatment regimens in the next two years. The first treatment regimen consisted of intravenous administration of 1 g methylprednisolone for three days followed by tapering with methylprednisolone tablets over eight weeks. The second regimen comprised two rounds of intravenous administrations of five days each, separated by a two-week treatment break, with no tapering. The regimen for the third round was five days of intravenous treatment, a treatment break of one week, five days of intravenous treatment, a ten-day treatment break, and then three days of intravenous treatment. This was followed by oral tapering over twelve weeks because review of the chest CT found a residual lesion that had been missed at the first treatment evaluation. MRI of the chest five months after the third and final treatment with methylprednisolone pulse therapy showed a sustained complete response.

Discussion

The WHO classifies thymomas by increasing malignancy; A, AB, B1, B2 and B3 (1, 2). Treatment options for metastatic thymoma in the Norwegian national guidelines are cytostatics containing cisplatin and anthracyclines, which are only effective in 16–36 % of patients and cardiotoxic (3). Immunotherapy has not shown promising results (2).

My experience with cancer has given me a deep insight and understanding of how fragile life is. The support from my doctors, family and other people close to me gave me the strength to try to find a treatment so that I could live. I am cancer-free today because I found a treatment which has produced great results, and which was not known or standardised in Norway, but which I hope will become so to help more people in the future.

We have found two studies involving the treatment of thymoma with methylprednisolone pulse therapy. In a prospective study with 17 patients who underwent surgery for invasive type AB–B3 thymoma, eight patients achieved preoperative partial response, and ten patients had no signs of recurrence after an average follow-up of 42 months (4). In a retrospective study with twelve patients with metastatic thymoma and myasthenia gravis, five patients achieved complete remission and seven achieved partial remission (5). After an average observation period of 14 months, ten patients were stable, one had received further treatment after 20 months due to pleural metastasis, and one had died from myasthenic crisis.

Furthermore, a significant response to glucocorticoid treatment has been described in a number of case reports, with complete or partial remission, even in metastatic disease.

Cytostatic regimens that include glucocorticoids have demonstrated better efficacy than cytostatics alone (6). The thymus is highly sensitive to glucocorticoids in the first place. Glucocorticoids induce atrophy and replace thymic tissue with fat and fibrosis (7). The effect is greatest in lymphocyte-rich tissue, but is also seen in epithelial cells. Tapering of glucocorticoid treatment over the course of several months may be preferable because thymoma cells have long division times and are in different division phases during pulse therapy.

Summary

In our opinion, glucocorticoid pulse therapy can be considered for inoperable and metastatic thymoma. When this type of treatment is attempted, it should be recorded, and the efficacy or otherwise should be reported.

The patient has consented to the publication of the article.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

WHO Classification of Tumours editorial board. Thoracic Tumours. 5. utg. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/Thoracic-Tumours-2021 Accessed 15.10.2022.

- 2.

Helsedirektoratet. Lungekreft, mesoteliom og thymom – handlingsprogram. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/lungekreft-mesoteliom-og-thymom-handlingsprogram Accessed 15.10.2022.

- 3.

Yu L, Zhang BX, Du X et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of chemotherapy for thymic epithelial tumors using the CD-DST method. Thorac Cancer 2020; 11: 1160–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Kobayashi Y, Fujii Y, Yano M et al. Preoperative steroid pulse therapy for invasive thymoma: clinical experience and mechanism of action. Cancer 2006; 106: 1901–7. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Qi G, Liu P, Dong H et al. Metastatic Thymoma-Associated Myasthenia Gravis: Favorable Response to Steroid Pulse Therapy Plus Immunosuppressive Agent. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23: 1217–23. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

Schmitt J, Loehrer PJ. The role of chemotherapy in advanced thymoma. J Thorac Oncol 2010; 5 (Suppl 4): S357–60. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Mimae T, Tsuta K, Takahashi F et al. Steroid receptor expression in thymomas and thymic carcinomas. Cancer 2011; 117: 4396–405. [PubMed][CrossRef]