Paraduodenal hernia is a rare form of congenital internal hernia and can lead to small bowel obstruction. This case report describes the case of a young boy who was admitted with acute exacerbation of chronic abdominal pain.

A previously healthy teenage boy had been suffering from abdominal pain for over a year. The pain was cramp-like in nature, in the centre of the abdomen, and lasted for several minutes a few times a week. The pain often subsided when the patient lay down flat. Following investigation by a paediatrician nine months previously, he was referred to the Department of Surgery for a small ventral hernia which was suspected to be the cause of the symptoms. He underwent surgery with direct closure of the fascia (using the Mayo technique), but this did not improve his symptoms.

Six months post-surgery, the boy was admitted to the Emergency Department following acute onset of abdominal pain lasting several hours. He recognised the pain from before, but reported that it had increased in severity and did not resolve as it used to. The pain was accompanied by nausea, and the boy had not had a bowel movement or passed wind since the pain started. He did not report any respiratory or urinary tract symptoms. In the Emergency Department, his abdomen was hard and generally tender to palpation with rebound tenderness. Bowel sounds were sparse on auscultation. Vital signs were unremarkable. Blood tests found leucocytes 17 × 109/L (reference range 3.5–10.0 × 109), while other blood test results were normal, including haematological tests, renal and liver function tests.

Pain relief treatment was initiated with 1 g paracetamol and 100 mg tramadol tablets. The patient was referred for abdominal ultrasound, which revealed a dilated small bowel. The patient was administered 2.5 mg intravenous morphine due to increasing pain. It was decided to refer the patient for abdominal CT with intravenous contrast due to suspected acute abdomen and pain that did not subside with analgesia.

The CT scan revealed a dilated small bowel with sudden calibre change in the central and left region of the abdomen, localised misty mesentery towards the dilated small bowel and faecalised small bowel content. Bowel ischaemia was not suspected, and no intra-abdominal free air or fluid was seen. The overall radiological evaluation raised suspicion of adhesive small bowel obstruction, which was not entirely consistent with the patient's age and absence of previous abdominal surgery.

Following the CT scan, the patient became tachycardic with a pulse of 120 bpm. His blood pressure was normal, he was still in pain and nauseous, and his entire abdomen was still tender to palpation with rebound tenderness. He was administered a 1 L intravenous infusion of Ringer's acetate. Surgery was found to be indicated based on the patient's clinical presentation and the radiological findings of suspected ileus.

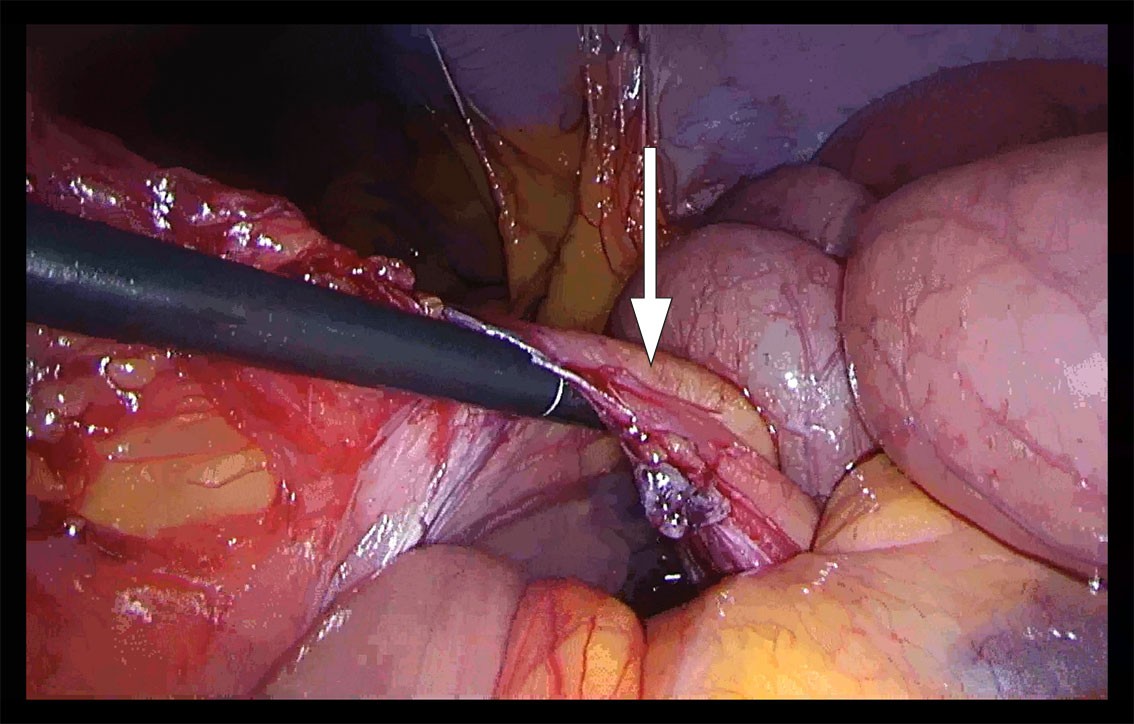

Laparoscopy was performed under general anaesthesia and found a small amount of intra-abdominal free fluid. Large areas of the small bowel were dilated. We started to reposition the small bowel to the right, firstly from proximal to distal and then in a proximal direction from the ileocaecal junction. It appeared that the small bowel was herniated under a 'cord' attached to the descending colon. On closer inspection, vascular structures could be made out, and we could not rule out the mesentery being narrow with a defect (Figure 1). Due to a large amount of dilated bowel in the surgical field, limited space and uncertainty about whether all the bowel had been repositioned, it was decided to convert to laparotomy. With a midline approach, we found mechanical small bowel obstruction from a left paraduodenal hernia with large areas of the small bowel herniated to the left, posterior to the inferior mesenteric vein. The repositioned small bowel appeared viable since there was good bowel motility and good blood circulation. Continuous sutures were placed with patent closure of the opening in the mesentery, without injuring the vascular structures.

The patient had no postoperative complications and was transferred to the ward that same afternoon. When the patient was discharged three days later, he had started to eat, was mobilised and had passed a bowel movement. He had pain over the surgical scar, which was managed with 1 g paracetamol and 50 mg tramadol as required. The patient reported being fully recovered at a telephone follow-up one month later. He had no abdominal pain and felt in good shape. He was exercising after two months.

Discussion

Internal hernias account for 0.5–0.9 % of cases of bowel obstruction (1). Paraduodenal hernia is the most common form (53 %) of congenital internal hernia (1). The literature mainly consists of case reports, with few cases in children being described (2).

The cause of paraduodenal hernia is failure of the mesentery to fuse with the peritoneum (3). Left paraduodenal hernia is due to a defect in the mesentery posterior to the inferior mesenteric vein, while right paraduodenal hernia is due to a defect posterior to the superior mesenteric vein. Most paraduodenal hernias occur to the left of the midline in the fossa of Landzert (75 %), while right paraduodenal hernias occur in the fossa of Waldeyer (4). Bowel obstruction can arise if spontaneous repositioning of the bowel does not take place.

It can be difficult to diagnose paraduodenal hernia because the symptoms are non-specific and range from chronic abdominal pain to acute abdomen. Men are affected more frequently than women (3:1), and the median age is 38 years (5). The diagnosis is often reached using abdominal CT (4).

On review of the patient's CT images, it could be seen that the inferior mesenteric vein runs anterior to the herniated small bowel loops. This was also seen intraoperatively and was consistent with the diagnosis of paraduodenal hernia (Figure 2).

The treatment of paraduodenal hernia is surgery, either by laparoscopy or laparotomy, with the objective of repositioning the small bowel and closing the opening in the mesentery (1). There are no clear guidelines for the surgical approach and how to avoid injury to the large mesenteric vessels. In paraduodenal hernia, care should be taken of the mesenteric vessels running to the anterior and medial side of the hernia, but division of these structures does not compromise blood supply to the bowel (6).

We started with laparoscopy, which is the preferred method, but had to convert to laparotomy (7).

A probable explanation for the patient's history of chronic intermittent abdominal pain is the small bowel sliding in and out of the fossa of Landzert. His acute abdominal pain was due to failure of the hernia to spontaneously reposition, thus trapping the small bowel. Surgery was performed relatively quickly and was successful, and the patient made a good postoperative recovery.

The patient and his parents have consented to the publication of the article.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Manojlović D, Čekić N, Palinkaš M. Left paraduodenal hernia - A diagnostic challenge: Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2021; 85: 106138. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

Abukhalaf SA, Mustafa A, Elqadi MN et al. Paraduodenal hernias in children: Etiology, treatment, and outcomes of a rare but real cause of bowel obstruction. Int J Surg Case Rep 2019; 64: 105–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Kadhem S, Ali MH, Al-Dera FH et al. Left Paraduodenal Hernia: Case Report of Rare Cause of Recurrent Abdominal Pain. Cureus 2020; 12: e7156. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Shadhu K, Ramlagun D, Ping X. Para-duodenal hernia: a report of five cases and review of literature. BMC Surg 2018; 18: 32. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Hassani KI, Aggouri Y, Laalim SA et al. Left paraduodenal hernia: A rare cause of acute abdomen. Pan Afr Med J 2014; 17: 230. [PubMed]

- 6.

Gabra A, Ageel MH. Laparoscopic treatment of pediatric paraduodenal hernia in Saudi Arabia. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2022; 84: 102382. [CrossRef]

- 7.

Parmar BPS, Parmar RS. Laparoscopic management of left paraduodenal hernia. J Minim Access Surg 2010; 6: 122–4. [PubMed][CrossRef]