In 2019, a total of 14 354 patients in Norway were registered as receiving treatment in an intensive care unit (ICU), of whom 59.2 % received mechanical ventilation (1). Mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU are vulnerable to wasting of skeletal and respiratory muscles as part of ICU-acquired weakness (2, 3). Muscle wasting may begin only a few hours after the start of intensive care treatment, and the degree of wasting can affect the hospital length of stay, survival, and the duration and outcomes of rehabilitation (2). In recent times there has been a move in intensive care medicine towards discontinuing sedation earlier in patients who are able to tolerate this, with patients encouraged to move and breathe as actively and as safely as possible (4). At the same time, those working in the ICU perceive a number of barriers to performing such interventions (5).

'Early mobilisation' encompasses interventions ranging from passive exercises and positioning to active exercises and transfers. Inspiratory muscle training refers to specific training of inspiratory muscles that can be performed while the patient is receiving mechanical ventilation.

Previous reviews have shown that early mobilisation and inspiratory muscle training in ICU patients can support the process of weaning from the ventilator and can improve outcomes (5–7). However, the methodological quality of the studies included in these reviews has been mixed, and in some cases, low. Only a few of the reviews assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) (8). A number of relevant primary studies have also been published since the most recent systematic review. In addition to using the GRADE approach, we included only randomised controlled trials with active interventions in intubated or tracheotomised patients, and excluded studies of low methodological quality.

The aim of our review was to compare early, active mobilisation (hereafter referred to as early mobilisation) and inspiratory muscle training with standard treatment in mechanically ventilated adults in the ICU.

Method

The review has been prepared in accordance with the PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews (9). The protocol has been published in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) with registration number CRD42017058780 (10). Prior to initiation of the work, a protocol amendment was made to add weaning time to the primary outcome measures.

To be selected, studies had to include patients over 18 years of age who received mechanical ventilation – following oral intubation or a tracheostomy – in an ICU setting. The interventions included were respiratory muscle training; active or active-assisted exercises for the extremities; mobilisation to the edge of the bed, or to a sitting (chair), standing or ambulatory position, and in-bed cycle ergometry. The control groups received no treatment, a different treatment or sham treatment. Primary outcome measures were the duration of mechanical ventilation, weaning time from the ventilator and mortality in the hospital, at 1–3 months, 1–6 months and after one year. Secondary outcome measures were ICU length of stay and hospital length of stay, as well as adverse events. Cochrane defines an adverse event as an unfavourable or harmful outcome that occurs during or after an intervention, but which is not necessarily caused by it. A distinction is made between serious and less serious adverse events (11). We included only published randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

With assistance from a senior librarian, we conducted a systematic search for literature published in the period 1 January 2006–27 April 2020 in the databases Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Cinahl, PubMed, PEDro, SweMed+, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), the Cochrane Library and OTseeker. We combined words from the text and keywords describing the population and intervention. The search was limited to English and Scandinavian languages, and to randomised controlled studies and systematic reviews (see Appendix 1 for detailed search strategy). In addition, we performed manual searches of UpToDate, Mobilization Network and Intensive Care Medicine, the journal of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Studies were selected by two authors independently reviewing the titles and abstracts, and then the full-text articles. The selection was based on predefined and piloted criteria (Box 1).

Design

Randomised controlled trials

Participants

Patients aged over 18 years

Patients who received mechanical ventilation in an ICU, with oral intubation or tracheostomy

Interventions

Respiratory muscle training

Active or active-assisted exercises for the extremities

Mobilisation to the edge of the bed, to sitting in a chair, or to a standing or ambulatory position

In-bed cycle ergometry

Comparison

Control group receiving a different treatment or no treatment

Primary outcome measures

Duration of mechanical ventilation

Weaning time from ventilator

Mortality in the hospital, at 1–3 months, 1–6 months and after 1 year

Secondary outcome measures

ICU length of stay

Hospital length of stay

Patient safety, adverse events

Publication date and language

Publication date 1.1.2006–27.4.2020

English or Scandinavian language

Only published studies were included

Exclusion criteria

Patients with injury- or disease-specific muscle wasting

Intervention was passive or almost exclusively passive

Studies with other outcome measures or publication years, or in other languages

Studies with high risk of bias

The extraction of data on study characteristics (Table 1) was performed by one author and verified by another. Data for the meta-analyses were extracted by two authors independently. The data were analysed in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) in a random effects model, as the studies showed relatively high clinical heterogeneity (12). For continuous variables, the overall effect was presented as the mean difference between the groups (MD) and the 95 % confidence interval (CI). For dichotomous variables, the overall effect was presented as an odds ratio (OR), an effect measure for the odds of an event at a given point in time, and 95 % CI. The statistical heterogeneity across studies is given as a percentage, I2.

Table 1

Overview of the randomised controlled trials included in the analysis (n = 17).

| First author, year |

Country |

Participants |

Intervention |

Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amundadottir, 2019 (31) |

Iceland |

n = 50 |

Early mobilisation 48 hours after inclusion, 20 minutes or more twice daily + standard treatment |

Early mobilisation 96 hours after inclusion, once daily + standard treatment |

| Burtin, 2009 (15) |

Belgium |

n = 90 |

Bedside cycle ergometry for 20 minutes, 5 days a week + standard treatment |

Standard treatment (respiratory physiotherapy and passive/active mobilisation of extremities + mobilisation out of bed if appropriate) |

| Condessa, 2013 (22) |

Brazil |

n = 92 |

Inspiratory muscle training twice daily, 7 days a week + standard treatment |

Standard treatment |

| Dantas, 2012 (17) |

Brazil |

n = 28 |

Early mobilisation according to standard protocol twice daily, 7 days a week, including exercises for the extremities and in-bed cycle ergometry |

Standard treatment (passive exercises for the extremities) |

| Dong, 2014 (27) |

China |

n = 60 |

Early mobilisation twice daily |

Not described |

| Dong, 2016 (16) |

China |

n = 106 |

Pre-surgical information and early mobilisation twice daily |

Rehabilitation with assistance from family following discharge from intensive care |

| Dos Santos1, 2018 (23) |

Brazil |

n = 28 |

Active exercises with resistance bands |

Passive exercises and positioning |

| Eggmann, 2018 (29) |

Switzerland |

n = 115 |

Early progressive mobilisation with in-bed cycle ergometry up to three times daily on weekdays + standard treatment |

Standard treatment (early mobilisation, respiratory physiotherapy and passive/active exercises) |

| Hodgson, 2016 (18) |

Australia/New Zealand |

n = 50 |

Early mobilisation according to standard protocol for one hour a day |

Unit's standard interventions: passive movement |

| Kho, 2019 (30) |

Canada |

n = 66 |

In-bed cycle ergometry + standard treatment |

Standard treatment (passive/active exercises and early mobilisation) |

| Martin, 2011 (21) |

USA |

n = 69 |

Inspiratory muscle training 5 days a week |

Breathing exercises with a sham inspiratory muscle training device 5 times a week. |

| Morris, 2016 (20) |

USA |

n = 300 |

Intensive early mobilisation according to standard protocol three times a day |

Standard treatment on weekdays when prescribed |

| Moss, 2016 (19) |

USA |

n = 120 |

Level-appropriate early mobilisation once a day |

Standard treatment three times a week (passive exercises, positioning and functional rehabilitation) |

| Schaller, 2016 (25) |

Germany |

n = 200 |

Early mobilisation across five levels |

Mobilisation in accordance with departmental guidelines |

| Schweickert, 2009 (26) |

USA |

n = 104 |

Early mobilisation once a day |

Standard treatment when prescribed |

| Tonella, 2017 (24) |

Brazil |

n = 19 |

Electronic inspiratory muscle training twice daily |

Intermittent nebuliser therapy |

| Wright, 2018 (28) |

UK |

n = 308 |

Intensive early mobilisation for 90 minutes on weekdays |

Standard treatment for 30 minutes on weekdays |

1One intervention group and one control group selected from a four-arm study

Continuous variables that were stated as medians and interquartile ranges were converted into means and standard deviations (SD) to enable them to be included in the meta-analyses (13). Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine whether the results of the meta-analyses were affected by the inclusion of these studies. Methodological quality was assessed independently by two authors according to the criteria in the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (14). A third party was consulted in the event of any disagreement. Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine whether the results were affected by the risk of bias. Subgroup analyses were performed within the early mobilisation studies, with respect to the number of treatments and the degree of activity in the control interventions. Two authors rated the certainty of evidence in the studies with low risk of bias using the GRADE approach (8). Publication bias was assessed as part of this approach.

Results

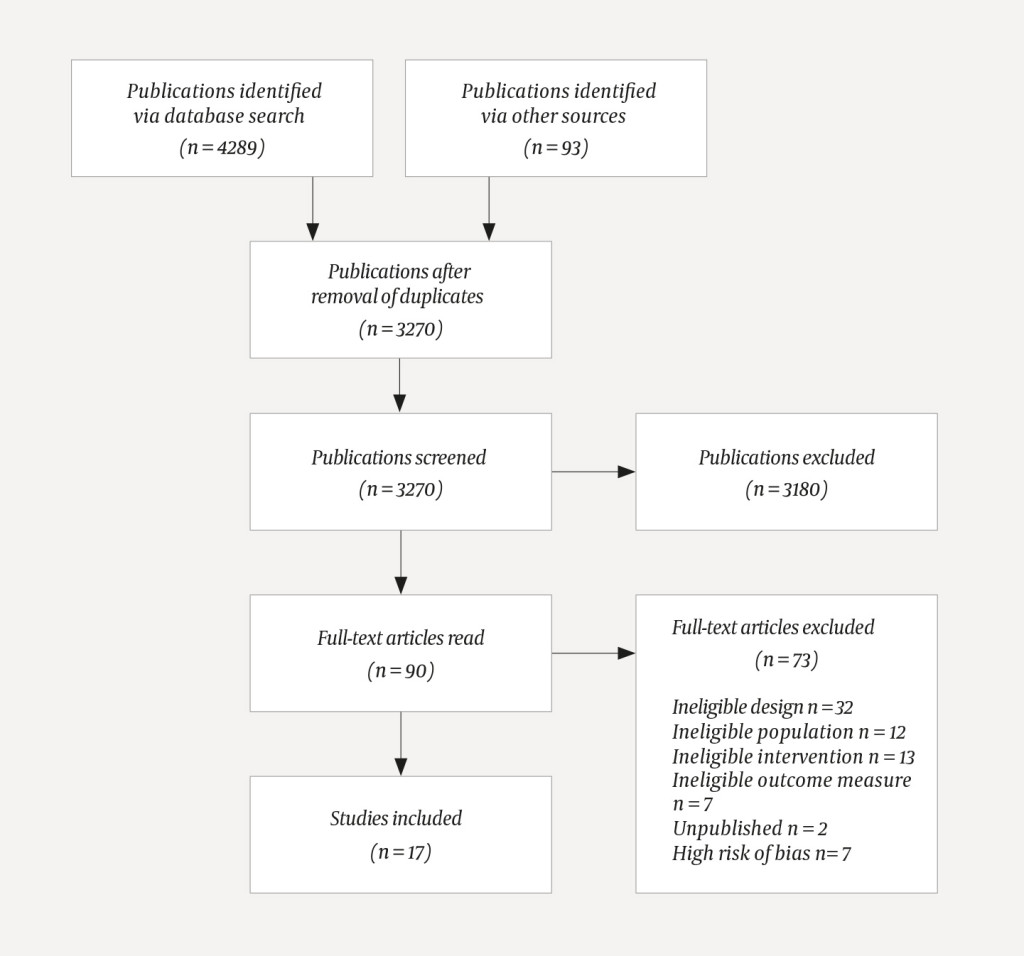

A total of 3 270 unique titles and abstracts were identified and read. Ninety of the articles were read in full text, with 17 studies included in the meta-analysis (15–31) and thus 73 excluded (Figure 1).

A total of 1 805 patients were included, with the number of participants per study ranging from 19 to 308. Results were presented for 1 782 patients. The average age was just under 60 years and 56.2 % of the participants were men. Thirteen of the studies included patients from mixed ICUs or ICUs of unspecified type (15), (17–19), (21–24), (27–31). Two of the studies included patients from medical ICUs (15, 17) and two from surgical ICUs (19, 21). Morbidity varied somewhat among the participants (Appendix 2). The intervention comprised inspiratory muscle training in three studies (24, 27)in-bed cycle ergometry in four studies (20, 26) and other forms of early mobilisation in ten studies (16), (18–20), (23), (25–28), (31). No studies of expiratory muscle training were identified that met our selection criteria. The control group interventions are referred to in the analyses as standard treatment, and consisted of no treatment, a different treatment or sham treatment. Common to participants in the control groups was that they received training that was more passive, less intensive, or administered later than the training in the intervention groups.

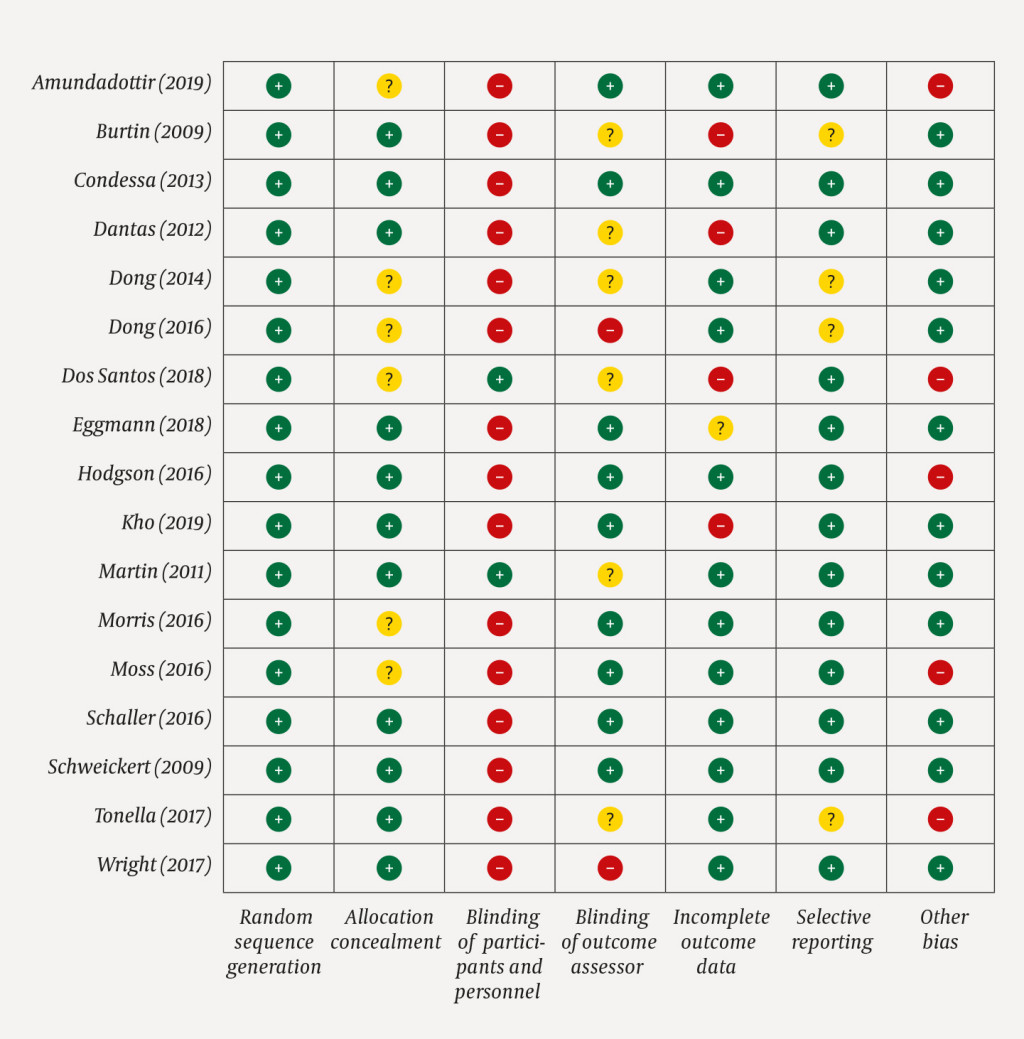

The risk of bias was low in nine of the studies included, and moderate in eight (Figure 2). None of the funnel plots indicated publication bias in the analyses (Appendix 3). The results of the studies with a low risk of bias are presented as follows.

Primary outcome

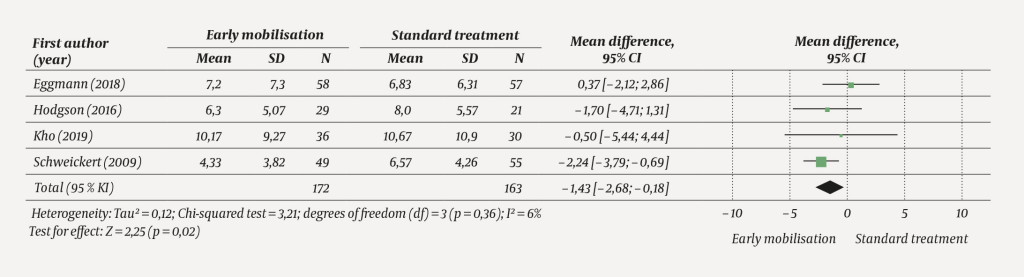

Compared with standard treatment, early mobilisation reduced the duration of mechanical ventilation (−1.43 days; 95 % CI −2.68 to −0.18, p = 0.02, four studies, 335 patients), with the certainty of evidence rated as moderate (Figure 3).

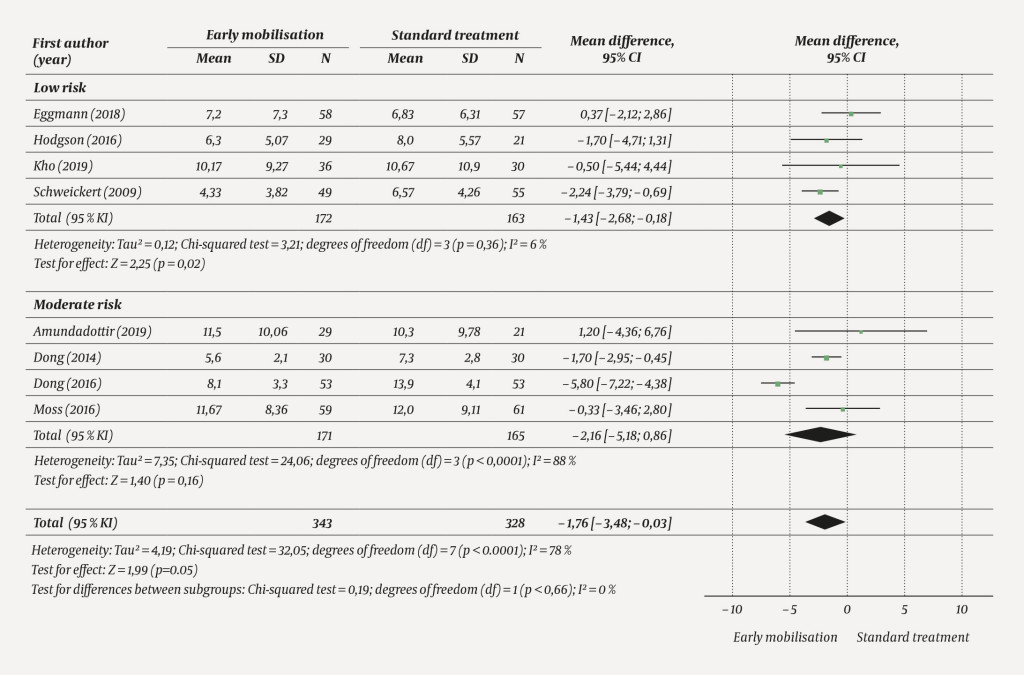

The inclusion of studies with a moderate risk of bias markedly increased the statistical heterogeneity, I2 = 78 %. The overall effect of early mobilisation was somewhat larger, but more uncertain (−1.76 days; 95 % CI −3.48 to −0.03, p = 0.05, eight studies, 671 patients) (Figure 4).

Compared with standard treatment, inspiratory muscle training had no effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation (−0.11 days; 95 % CI −1.76 to 1.53, p = 0.89, two studies, 146 patients), with the certainty of evidence rated as low (data not shown, available from first author on request).

Weaning time was not reported in the early mobilisation studies with a low risk of bias. No difference was seen in weaning time with inspiratory muscle training versus standard treatment (−0.33 days; 95 % CI −1.31 to 0.65, p = 0.51, one study, 77 patients), with the certainty of evidence rated as low (data not shown, available from first author on request).

Meta-analyses based on moderate certainty evidence found no effect of the training on mortality (data not shown, available from first author on request).

Secondary outcomes

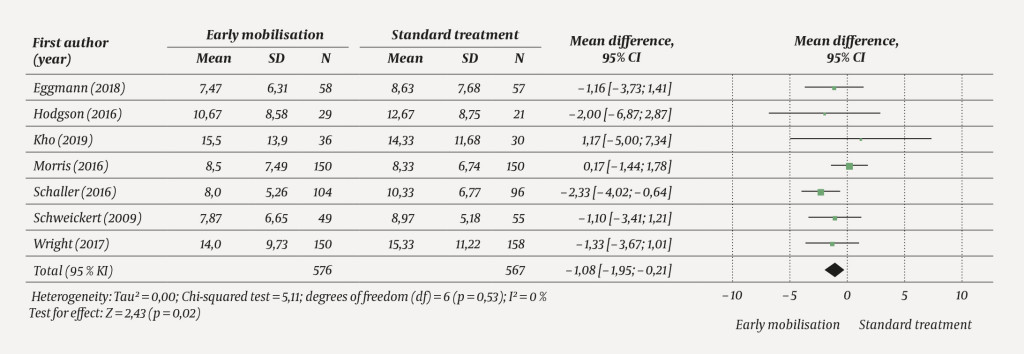

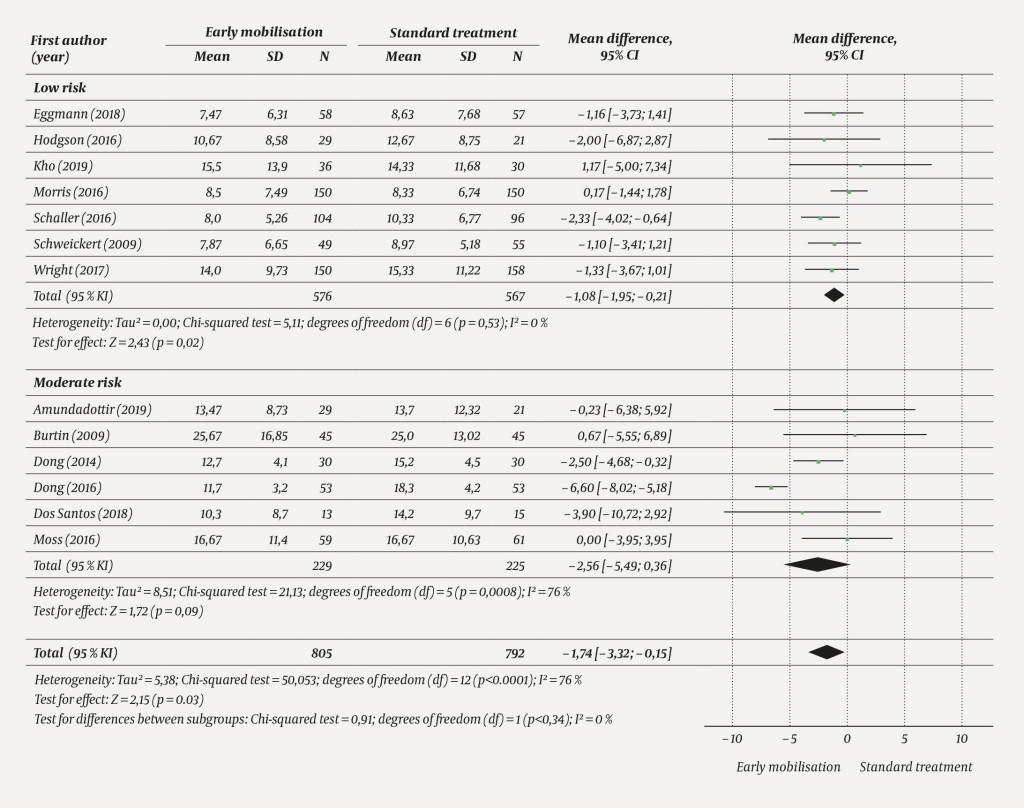

Compared with standard treatment, early mobilisation reduced the ICU length of stay (−1.08 days; 95 % CI −1.95 to −0.21, p = 0.02, seven studies, 1 143 patients), with the certainty of evidence rated as moderate (Figure 5).

The inclusion of studies with a moderate risk of bias markedly increased the statistical heterogeneity, I2 = 76 %. The overall effect of early mobilisation was somewhat larger, but more uncertain (−1.74 days; 95 % CI −3.32 to −0.15, p = 0.03, 13 studies, 1 597 patients) (Figure 6). There was no effect on hospital length of stay (data not shown, available from first author on request), with the certainty of evidence rated as moderate. No studies reported the effect of inspiratory muscle training on length of stay.

The certainty of the evidence according to GRADE is summarised in Tables 2a and b, along with the reasons for downgrading the evidence

Table 2a

Overall results and rating of evidence certainty according to GRADE. MD = mean difference, OR = odds ratio.

| Outcome measure |

|

Absolute effect (95 % CI) |

|

Relative effect |

Number of participants |

Certainty of evidence (GRADE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Risk associated with standard treatment |

Risk associated with early mobilisation |

|

||||

| Duration of mechanical ventilation |

|

– |

MD 1.43 lower |

|

- |

335 (4) |

Moderate1 |

| Hospital mortality |

|

161 per 1 000 |

12 per 1 000 |

|

OR 0.90 |

835 (6) |

Moderate2 |

| Mortality after 1–3 months |

|

73 per 1 000 |

34 per 1 000 |

|

OR 0.51 |

200 (1) |

Moderate3 |

| Mortality after 1–6 months |

|

200 per 1 000 |

20 per 1 000 |

|

OR 0.95 |

723 (3) |

Moderate2 |

| ICU length of stay |

|

– |

MD 1.08 lower |

|

– |

1 143 (7) |

Moderate2 |

| Hospital length of stay |

|

– |

MD 0.62 lower |

|

– |

1 143 (7) |

Moderate2 |

1Total number of participants < 400

2Wide confidence intervals

3Only one study in the analysis

Table 2b

Overall results and rating of evidence certainty according to GRADE. MD = mean difference, OR = odds ratio.

| Outcome measure |

|

Absolute effect (95 % CI) |

|

Relative effect |

Number of participants |

Certainty of evidence (GRADE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Risk associated with standard treatment |

Risk associated with inspiratory muscle training |

|

||||

| Duration of mechanical ventilation |

|

– |

MD 0.11 lower |

|

– |

146 (2) |

Low1, 2 |

| Weaning time from ventilator |

|

– |

MD 0.33 lower |

|

– |

77 (1) |

Low1,3 |

| Hospital mortality |

|

99 per 1 000 |

36 per 1 000 (78 to 77) |

|

OR 0.62 |

161 (2) |

Moderate2 |

1Total number of participants < 400

2Wide confidence intervals

3Only one study in the analysis

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses of continuous variables were performed for all studies of early mobilisation, with the subgroups based on the number of treatments and how active the control interventions were. None of the resulting forest plots showed significant differences between the subgroups (data not shown, available from first author on request).

Patient safety

Thirteen of the 17 studies reported whether adverse events had occurred (15), (18–22), (24–30). However, the reporting was inadequate in several studies (Appendix 4). Only two serious adverse events were reported: bradycardia and a fall in oxygen saturation to below 80 % (15, 18). No adverse events were reported in studies of inspiratory muscle training (22, 24). The number of training sessions was not stated. Seven studies of early mobilisation reported both the number of adverse events and the number of training sessions in the intervention groups (20, 26)(28–30). In these studies, a total of 79 adverse events were reported over the course of 5 675 training sessions, which corresponds to an incidence rate of 1.4 %. We have included in the calculations 35 events in two studies that resulted in the intervention being discontinued prematurely (21, 22, 24). In the control groups, there was inadequate reporting of the number of adverse events and/or sessions. As a result, we found that the interventions resulted in a low number of adverse events; however, there was an insufficient basis for comparison to the control groups. A complete overview of all adverse events is presented in Appendix 4.

Sensitivity analysis

In the studies with a low risk of bias, there was an insufficient basis for sensitivity analyses of the converted values (data not shown, available from first author on request).

Discussion

This systematic review included 17 randomised controlled trials of inspiratory muscle training and early mobilisation. The meta-analyses show that early mobilisation can reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation and the ICU length of stay. On the basis of a single study, we found no effect of early mobilisation on the weaning time. Early mobilisation also had no effect on mortality or hospital length of stay. The analyses revealed no effect of inspiratory muscle training on duration of mechanical ventilation or ventilator weaning, or on hospital mortality.

The evidence base for analysing the effects of inspiratory muscle training was small, and the results must be interpreted with caution. Few adverse events were described in association with the use of early mobilisation or inspiratory muscle training, and only two serious adverse events were reported.

We found that early mobilisation reduced the duration of mechanical ventilation by an average of 1.5 days compared with standard treatment. Connolly et al. also reported a positive effect of early mobilisation on the duration of mechanical ventilation in their review of systematic reviews (32). We found no effect of inspiratory muscle training on the same outcome measure. Reducing the duration of mechanical ventilation is a stated aim of the Norwegian Intensive Care Registry in their annual report from 2019 (1). Shorter ventilation time is likely to lead to fewer complications, as well as increased capacity and reduced costs for ICUs.

We were unable to identify any studies with a low risk of bias that had examined the effect of early mobilisation on weaning time, and we found only one study that had examined the effect of inspiratory muscle training on this outcome measure. In systematic reviews, Vorona et al. found an effect of inspiratory muscle training on weaning time (33), while Elkins et al. found that it increased the proportion of successful weaning attempts (34). Weaning time from mechanical ventilation depends on several factors, including the criteria used to confirm the patient as ready for weaning, as well as the manner in which the weaning is performed (34).

Our analyses showed no effect on mortality of either early mobilisation or inspiratory muscle training. Two previous systematic reviews comparing early mobilisation with standard treatment also found no differences in mortality between the groups (35, 36).

Early mobilisation reduced the length of ICU stays by about one day, but we were unable to demonstrate an effect on the total length of stay in hospital. Kayambu et al. found an effect on length of stay both in the ICU and in hospital (36). Shorter stays in the ICU will, like a shorter duration of mechanical ventilation, lead to fewer complications for patients and potentially give rise to increased capacity and reduced costs for hospitals.

We found few adverse events. They were reported in only 1.4 % of all mobilisation sessions across the studies. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis found that adverse events occurred in 2.6 % of mobilisation sessions, with negative consequences for the patient in 0.6 % of cases (37). No adverse events were reported in the studies of inspiratory muscle training. Allowance must be made for the possibility that some adverse events went unreported. Another challenge is that adverse events were defined differently across the studies, and in some studies they were not predefined (11). However, primary research studies have shown that early mobilisation in the ICU is safe and feasible (37, 38).

Our analysis has certain methodological limitations. The treatments used in the studies of early mobilisation varied across both the intervention and the control groups, and were poorly described for the control groups in several studies. These factors may have affected the results, which may have become more heterogeneous. We performed subgroup analyses in an attempt to group together studies that were more similar to one another, but found no significant differences between the groups. A known problem in intensive care research, where there is relatively high early mortality is that it can be difficult to obtain good follow-up data. This may have confounded the outcome measures in the current review (39).

Blinding was performed in only two of the studies included in the meta-analyses (21, 23). It is difficult to blind participants and personnel to the interventions featured in this study. We scored the lack of blinding as high risk, but did not deduct for it when deciding the GRADE rating, because we do not believe it affected the results. In their meta-epidemiological review of 146 meta-analyses, Wood et al. found little evidence to suggest that lack of blinding leads to exaggerated intervention effect estimates when objective outcome measures are used (40).

We reported hard outcome measures that say nothing about quality of life, self-reliance and other patient-reported outcomes. Such outcome measures are clinically relevant and are of great importance to patients and their families. Tipping et al. found that intensive early mobilisation was associated with increased quality of life after six months (35).

Our systematic review and meta-analysis have a number of strengths. We conducted a thorough, systematic literature search. Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment were performed by two authors independently, thereby increasing the quality of the work. The quality of the studies themselves is also relatively high, as we excluded all those with a high risk of bias.

Our findings have clinical implications in that they suggest that mechanically ventilated adults in the ICU should undergo early mobilisation. Studies have shown that this is safe and feasible (38, 41). However, there are a number of perceived barriers to early mobilisation in the ICU (42), and point-prevalence studies have shown that early mobilisation of ICU patients is rarely performed in practice (43, 44). In a study of mobilisation practices in the ICU at Stavanger University Hospital, Øvrebø found that patients were first mobilised after an average of eight days of mechanical ventilation. Five days passed on average from the point at which the patients were ready for mobilisation until they were first mobilised. On day shifts, 40 % of ventilated patients who were ready for mobilisation were in fact mobilised, and only 21 % on evening shifts. This study reveals a need in Norway, too, for quality assurance work with regard to early mobilisation of ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilation (45).

All the interventions in our meta-analyses are currently the subject of ongoing studies. It will be particularly interesting to see the results of studies of in-bed cycle ergometry, as most studies to date have focused solely on the safety and feasibility of this type of mobilisation.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis show that early mobilisation of mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients probably shortens the duration of mechanical ventilation and the ICU length of stay. Early mobilisation and inspiratory muscle training probably have no effect on mortality. Inspiratory muscle training may have little or no effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation or weaning time. Relatively few studies have examined inspiratory muscle training to date, however, and further studies are required. Additional studies should be conducted on long-term patient-reported outcome measures, and studies will hopefully provide more information about the effects of in-bed cycle ergometry.

Thank you to Mikaela Aamodt for assistance with updated searches, and to Kristin Brautaset for valuable input and for advice on methodology.

This article has been peer-reviewed.

Main findings

Early mobilisation of mechanically ventilated patients probably results in a slightly shorter duration of ventilation.

Inspiratory muscle training may have little or no effect on the weaning time from mechanical ventilation.

Early mobilisation and inspiratory muscle training probably have no effect on mortality, and few adverse events have been reported.

- 1.

Buanes EA, Kvåle R, Barratt-Due A. Årsrapport for 2019 med plan for forbetringstiltak. Versjon 1.1. Bergen: Norsk intensivregister, 2020. https://www.kvalitetsregistre.no/sites/default/files/37_arsrapport2019_norsk_intensivregister.pdf Accessed 19.3.2021.

- 2.

Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA 2013; 310: 1591–600. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Parry SM, El-Ansary D, Cartwright MS et al. Ultrasonography in the intensive care setting can be used to detect changes in the quality and quantity of muscle and is related to muscle strength and function. J Crit Care 2015; 30: 1151.e9–14. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Needham DM. Mobilizing patients in the intensive care unit: improving neuromuscular weakness and physical function. JAMA 2008; 300: 1685–90. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Cameron S, Ball I, Cepinskas G et al. Early mobilization in the critical care unit: A review of adult and pediatric literature. J Crit Care 2015; 30: 664–72. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

Moodie L, Reeve J, Elkins M. Inspiratory muscle training increases inspiratory muscle strength in patients weaning from mechanical ventilation: a systematic review. J Physiother 2011; 57: 213–21. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Zhang L, Hu W, Cai Z et al. Early mobilization of critically ill patients in the intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0223185. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations: The GRADE Working Group, 2013. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html Accessed 19.3.2021.

- 9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

2021. National Institute for Health Research. Prospero. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ Accessed 19.3.2021.

- 11.

Peryer G, Golder S, Junqueira D et al. Chapter 19: Adverse effects. I: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 61. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-19 Accessed 19.3.2021.

- 12.

Review Manager (RevMan). Dataprogram. 5.3 ed. København: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

- 13.

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 135. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al. Kapittel 8. I: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2. utgave. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2019.

- 15.

Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robbeets C et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: 2499–505. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Dong Z, Yu B, Zhang Q et al. Early rehabilitation therapy is beneficial for patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation after coronary artery bypass surgery. Int Heart J 2016; 57: 241–6. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 17.

Dantas CM, Silva PF, Siqueira FH et al. Influence of early mobilization on respiratory and peripheral muscle strength in critically ill patients. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2012; 24: 173–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 18.

Hodgson CL, Bailey M, Bellomo R et al. A binational multicenter pilot feasibility randomized controlled trial of early goal-directed mobilization in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2016; 44: 1145–52. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 19.

Moss M, Nordon-Craft A, Malone D et al. A randomized trial of an intensive physical therapy program for patients with acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193: 1101–10. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Morris PE, Berry MJ, Files DC et al. Standardized rehabilitation and hospital length of stay among patients with acute respiratory failure: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315: 2694–702. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 21.

Martin AD, Smith BK, Davenport PD et al. Inspiratory muscle strength training improves weaning outcome in failure to wean patients: a randomized trial. Crit Care 2011; 15: R84. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 22.

Condessa RL, Brauner JS, Saul AL et al. Inspiratory muscle training did not accelerate weaning from mechanical ventilation but did improve tidal volume and maximal respiratory pressures: a randomised trial. J Physiother 2013; 59: 101–7. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Dos Santos FV, Cipriano G, Vieira L et al. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation combined with exercise decreases duration of mechanical ventilation in ICU patients: A randomized controlled trial. Physiother Theory Pract 2020; 36: 580–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 24.

Tonella RM, Ratti LDSR, Delazari LEB et al. Inspiratory muscle training in the intensive care unit: A new perspective. J Clin Med Res 2017; 9: 929–34. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 25.

Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M et al. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 1377–88. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 26.

Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 373: 1874–82. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 27.

Dong ZH, Yu BX, Sun YB et al. Effects of early rehabilitation therapy on patients with mechanical ventilation. World J Emerg Med 2014; 5: 48–52. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 28.

Wright SE, Thomas K, Watson G et al. Intensive versus standard physical rehabilitation therapy in the critically ill (EPICC): a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2018; 73: 213–21. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 29.

Eggmann S, Verra ML, Luder G et al. Effects of early, combined endurance and resistance training in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0207428. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 30.

Kho ME, Molloy AJ, Clarke FJ et al. Multicentre pilot randomised clinical trial of early in-bed cycle ergometry with ventilated patients. BMJ Open Respir Res 2019; 6: e000383. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 31.

Amundadottir OR, Jonasdottir RJ, Sigvaldason K et al. Effects of intensive upright mobilisation on outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial with 12-months follow-up. Eur J Physiother 2019; 21: 68–78. [CrossRef]

- 32.

Connolly B, O'Neill B, Salisbury L et al. Physical rehabilitation interventions for adult patients during critical illness: an overview of systematic reviews. Thorax 2016; 71: 881–90. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 33.

Vorona S, Sabatini U, Al-Maqbali S et al. Inspiratory muscle rehabilitation in critically ill adults. A systematic review and metaanalysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 735–44. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 34.

Elkins M, Dentice R. Inspiratory muscle training facilitates weaning from mechanical ventilation among patients in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. J Physiother 2015; 61: 125–34. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 35.

Tipping CJ, Harrold M, Holland A et al. The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2017; 43: 171–83. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 36.

Kayambu G, Boots R, Paratz J. Physical therapy for the critically ill in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2013; 41: 1543–54. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 37.

Nydahl P, Sricharoenchai T, Chandra S et al. Safety of patient mobilization and rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit. Systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017; 14: 766–77. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 38.

Bailey P, Thomsen GE, Spuhler VJ et al. Early activity is feasible and safe in respiratory failure patients. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 139–45. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 39.

Egleston BL, Scharfstein DO, Freeman EE et al. Causal inference for non-mortality outcomes in the presence of death. Biostatistics 2007; 8: 526–45. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 40.

Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2008; 336: 601–5. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 41.

Sricharoenchai T, Parker AM, Zanni JM et al. Safety of physical therapy interventions in critically ill patients: a single-center prospective evaluation of 1110 intensive care unit admissions. J Crit Care 2014; 29: 395–400. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 42.

Dubb R, Nydahl P, Hermes C et al. Barriers and strategies for early mobilization of patients in Intensive Care Units. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13: 724–30. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 43.

Berney SC, Harrold M, Webb SA et al. Intensive care unit mobility practices in Australia and New Zealand: a point prevalence study. Crit Care Resusc 2013; 15: 260–5. [PubMed]

- 44.

Nydahl P, Ruhl AP, Bartoszek G et al. Early mobilization of mechanically ventilated patients: a 1-day point-prevalence study in Germany. Crit Care Med 2014; 42: 1178–86. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 45.

Øvrebø L, Hansen BS. Mobiliseringsaktivitet hos intensivpasienter. Inspira Tidsskrift for anestesi- og intensivsykepleiere 2019; 2: 16–23.