Food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders – a systematic literature review

Main findings

We found a high prevalence of food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range.

Sensitivity particularly to food textures and taste, and a high degree of autism symptoms, were of significance to the prevalence and characteristics of the food selectivity patterns.

Individuals with autism spectrum disorders present with persistent difficulties with social communication and interaction as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour and interests (1). The international diagnostic classification standard ICD-10 splits the condition into subtypes (childhood autism, Asperger syndrome, atypical and unspecified) based on the time of debut, symptoms and whether there is delayed language and cognitive development (intellectual ability level). Asperger syndrome is used when the child's language and intellectual ability is normal (intelligence quotient (IQ) ≥ 70). In Norway, those whose intellectual ability level is assumed to be in the normal range tend to be assessed by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

Food selectivity includes refusing food intake, fear of new foods (neophobia), a strong preference for certain types of food and/or a severely restricted food repertoire (2). Such eating patterns can have a serious impact on children's somatic health (3). Food selectivity is not a formal diagnosis; the literature provides a variety of slightly different definitions as symptoms are measured in different ways. Nevertheless, the severity of these symptoms has been recognised in the US diagnostic system (DSM-5) through the diagnosis 'Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder' (ARFID) (4). The ARFID criteria requires the restrictive eating patterns to have growth-related, nutritional and psychosocial consequences, without a desire to lose weight.

Seven studies were identified in the first review article on food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, and a high prevalence (46–89 %) was established (5). The considerable variation can be explained in part by the fact that the studies measured eating patterns in different ways (questionnaires, direct observation of the child, and eating difficulties as a reason for referral). One meta-analysis reported a prevalence that was approximately five times higher in children with autism spectrum disorders than in the general child population (2). However, the prevalence was assessed for all diagnostic subgroups combined.

The last ten years have seen increasing interest in food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, and several review articles have recently been published (6–8). One of these summarised findings from 56 original papers and concluded that food selectivity patterns similar to those used in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria occur frequently in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (6).

The eating patterns were particularly associated with sensory sensitivity (hyper and hypo sensitivity to food textures and taste, etc.), but also neophobia and a lack of interest in food. Included in the review were 38 separate case studies of severe avoidant restrictive food intake disorders that had considerable somatic consequences in the form of low weight/weight loss, impaired growth or development, and deficiencies (anaemia, rickets), but also overweight due to an intake of high-energy foods only (6).

Two review articles that primarily investigated the characteristics of food selectivity, but that did not require the ARFID criteria to be met, found an association between sensory sensitivity and food selectivity (7, 8). Only one of them (8) reported on somatic consequences, and these were less severe (primarily obstipation and weight impact) than those described in the review article about avoidant/ restrictive food intake disorder (6). All the review articles included studies of heterogenous autism groups (which meant large variation in intellectual ability levels), and all the articles included pre-school children, who at group level have proved to display clearer autism symptoms (as in childhood autism) and a lower intellectual ability level (9). The broad inclusion obscures whether the findings apply equally to those with an intellectual ability level in the normal range (like for Asperger syndrome).

This systematic review article maps the prevalence, characteristics and somatic consequences of food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, focusing on those with an intellectual ability level in the normal range.

Knowledge base

The MEDLINE and PsycInfo (Ovid) databases were searched until the end of June 2024. We used the databases' own subject headings (Medical Subject Headings, MeSH) as well as various variants and combinations of truncated (*) search terms and proximity operators (ADJ) (for detailed information on search strings, see Table 1 and Appendix 1). We included original papers, including case studies, that examined the prevalence, characteristics and/or somatic consequences of food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and that involved participants with an intellectual ability level in the normal range and with a mean age of 6–18 years. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in more detail in Table 1 (see also Appendix 2).

Table 1

The search terms, inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria of our literature review.

| Population | Autism spectrum disorder OR asperger OR PDD-NOS OR autism OR autistic OR ASD OR highfunctioning autism OR high-functioning ASD |

| Definition of eating patterns | Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder OR ARFID OR restrictive eating OR restrictive intake disorder OR neophobia OR select eating OR picky eating |

| Age | Child OR adolescent OR youth OR young OR juvenile OR teenage OR teen-age |

| Period | Until the end of June 2024 (going as far back as possible) |

| Inclusion criteria | Original papers (including case studies) in English on the prevalence, characteristics and/or consequences of food selectivity (broadly defined: eating a small selection of foods/or refusing to taste new foods (neophobia) and ARFID (avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder) in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, involving participants with an intellectual ability level in the normal range and/or with Asperger syndrome, not limited to young children (mean age 6–18 years) |

| Exclusion criteria | Articles that do not discuss the prevalence or characteristics or consequences of food selectivity in autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range, or that are generally restricted to young children (mean age < 6 years) |

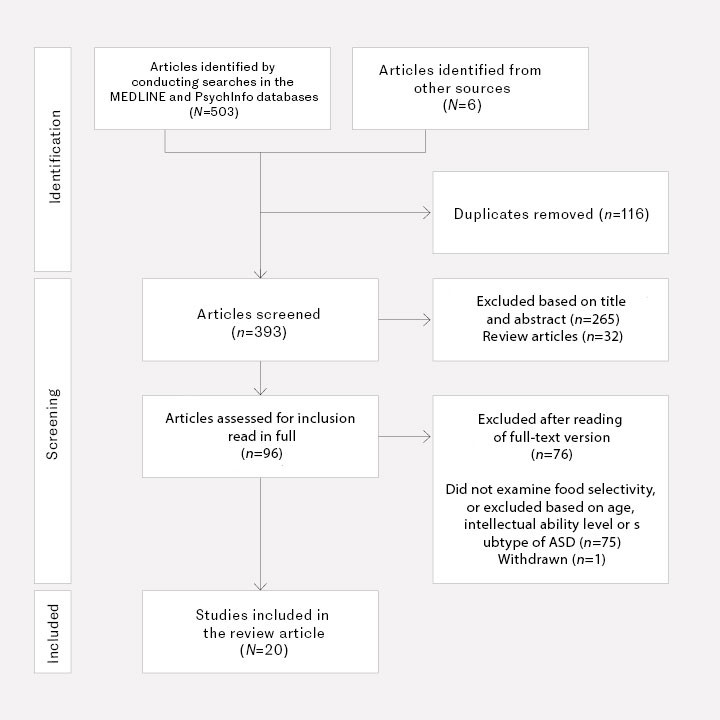

The articles' relevance was assessed independently by two of the authors (MM and KRØ) based on their title and abstract; any disagreement was resolved by consensus. Out of 503 articles, full-text versions of 96 were read by both authors; 20 were included in the literature review (Figure 1). In order to rank the included studies, one author (BØ) applied the GRADE system's four confidence ratings: very low, low, moderate and high (10). These were then considered by a different author (KRØ), and any ranking disagreement was resolved by consensus. For our descriptive study, which is not suitable for calculating effect sizes, we opted to assess consistency between findings, the number of studies and their size.

Results

We identified a total of 20 articles (Table 2) (11–30), of which twelve specified prevalence. The others included only other findings (characteristics and somatic consequences).

Table 2

Included studies on food selectivity in autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Studies that specified prevalence are highlighted in bold, case studies are highlighted in italics. ARFID = Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder.

| Studies, | Design and participants. Number (n), age and intellectual ability level (IQ) | Food selectivity measure | Prevalence of food selectivity (%) and other study findings (characteristics and somatic consequences) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bandini, 2010 | Clinical study, N = 53 ASD + 58 control individuals | The Food frequency | Refusal of certain types of food in 42 % of ASD individuals versus 19 % in control individuals. | |

| Bandini, 2017 | Clinical progress study, | The FFQ & the Meals in Our Household Questionnaire (MIOH) | 47 % at 7 years and 31 % at 13 years. | |

| Chistol, 2018 (21) | Clinical study, N = 53 ASD + 58 control individuals | FFQ & The Sensory Profile | Atypical oral sensitivity that was also associated with food selectivity was displayed by 64 % in ASD individuals versus 7 % in control individuals. | |

| Dominick, 2007 | Clinical study, N = 67 ASD + 39 with language impairments Mean age 7 years | The Atypical Behavior | 76 % in ASD individuals versus 15 % in individuals with language impairments. | |

| Harris, 2021 (25) | Population study, N = 2 818, of whom 39 score over the ASD symptom threshold Mean age 6 and 10 years respectively at two different times. Mean of whole population non-verbal IQ = 105 | The Stanford Feeding Questionnaire | Prevalence not specified but saw an association between autistic traits and obstipation and found that food selectivity mediates this. | |

| Hubbard, 2014 | Clinical study, N = 53 ASD + 58 control individuals | FFQ and interview questions (food texture, mixing of foods, temperature, separating foods, colour, brand and shape) | 36 % of ASD individuals versus 16 % of control individuals had > 3 of 7 investigated problems associated with food characteristics. | |

| Kamal Nor, 2019 | Clinical study, N = | Brief Autism Mealtime | Assessed the consequence of ASD: Obesity 11 % and overweight 22 %. | |

| Kazek, 2021 (12) | Clinical study, N = 41 ASD + 34 control individuals Median age 7 years | The Child's Current Nutritional Status, 20 | 63 % in ASD individuals versus 26 % in control individuals. Food selectivity was associated with sensory sensitivity. | |

| Calisan-Kinter, 2024 (22) | Clinical study, N = 37 ASD with ARFID, 37 without ARFID + 37 control individuals | Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ) | Prevalence not specified but association found between food selectivity and ASD symptoms, lower intellectual ability level and increased sensory sensitivity. | |

| Koomar, 2021 | Population study, | Nine-item ARFID Screen (NIAS) and additional questions about food selectivity | 21 % diagnosed with ARFID. | |

| Kuschner, 2015 | Clinical study, N = 65 ASD + 59 control individuals Mean age 16 years | The self-report Adult/ | 57 % neophobia in ASD individuals versus 32 % in control individuals Food selectivity was associated with sensory sensitivity. | |

| Mayes, 2019 (13) | Clinical study, | Checklist for Autism | 70 % in ASD individuals, 13 % in individuals with other diagnoses and 5 % in control individuals. | |

| Nadon, 2011 (19) | Clinical study, N = 95 ASD | The Eating Profile & The Short Sensory Profile | Prevalence not specified, found association between food selectivity and sensory sensitivity, but not intellectual ability level. | |

| Planerova, 2017 | Case study, boy with Asperger syndrome | Clinical interview | Consequence: Severe vitamin C deficiency | |

| Postorino, 2015 | Clinical study, N | The revised FFQ | 50 % had food selectivity. | |

| Rajendram, 2021 | Case study, boy | Clinical interview | Consequence: Severe malnutrition | |

| Roth, 2010 (29) | Case study, boy with Asperger syndrome | Clinical interview | Consequence: Severe malnutrition | |

| Valicenti- | Clinical study, N = 50 ASD + 50 with other diagnoses + 50 control individuals | Childhood Autism | 60 % in ASD individuals, 36 % in individuals with other development disorders and 33 % in control individuals. | |

| Van't Hof, 2020 (24) | Population-based cohort study, N = | Children's Eating | Prevalence not specified, but ASD symptom scores at 6 years of age were associated with later food selectivity. | |

| Zickgraf, 2018 | Clinical study, N = | Checklist for Autism | Food selectivity in 71 % of ASD individuals | |

Prevalence

While there was a considerable spread in prevalence rates for food selectivity in those with autism spectrum disorders, from 21 % to 76 %, these rates were consistently higher than in the control individuals in the respective studies. A large questionnaire-based cohort study (N = 5 157, mean age 11 years) showed a relatively low prevalence (21 %), which may have been caused by the authors' use of ARFID criteria (11). This study showed that avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder occurred similarly when a majority (83 %) of the sample had an intellectual ability level in the normal range, but the study did not correct for intellectual ability level.

Seven studies compared the prevalence of food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders to the prevalence in control individuals (12–18). These studies reported that food selectivity was displayed by 42–76 % of the children with autism spectrum disorders compared to 5–33 % of the control individuals (Table 2). One of these studies asked young people between 12–28 years of age to self-report on a few questions. The results indicated that those with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range (IQ > 75) (n = 65) suffered from neophobia and food selectivity more frequently than the control individuals (n = 59) (15). Another study that similarly asked a few specific questions showed that 70 % of those with autism spectrum disorders (n = 1 462, of which 70 % had IQ > 80) declared that they had food selectivity, compared to 5 % of the control individuals (13). There was a high proportion of boys (68–92 %) in all the above-mentioned study populations. Overall, we had high confidence in this finding due to consistency in the reported high prevalence of food selectivity in individuals with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range.

Sensory sensitivity

A total of eight studies explained food selectivity by pointing to a high level of sensory sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual abilities in the normal range (11–13, 15, 18–21). Several studies related sensory sensitivity to food textures, but in the above-mentioned large cohort study, sensitivity to taste was the clearest cause of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (11). Two studies compared children with autism spectrum disorders with and without food selectivity. One of them found that sensitivity to textures, smell/taste and visual/auditive impressions was associated with food selectivity, but a majority of the children in this study had childhood autism (61 % of 95 children), although 67 % had an intellectual ability level in the normal range (19). The average intellectual ability level of participants in the other study was in the normal range, and here it was found that 68 % of those with food selectivity were sensitive to the texture of food, approximately half (53 %) to taste, while fewer were sensitive to other factors (such as colour, shape, smell) (20).

In five studies, children with autism spectrum disorders were compared to control individuals without this condition (12, 13, 15, 18, 22). It was found that sensory sensitivity to the texture and taste of food was a key characteristic (approximately 2–10 times more frequent in the children with autism spectrum disorders than in the control individuals). Two of the studies included only children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range (12, 15). Both studies reported that sensitivity to texture was a cause of food selectivity, but one of them also found that neophobia and sensitivity to taste were key (15). One study compared a group of children with an average intellectual ability level in the lower parts of the normal range to control individuals. This study also showed that sensitivity to texture was the most common cause of food selectivity among those with autism spectrum disorders, but this was also frequently reported by the control individuals (77 % versus 36 %, with a standardised questionnaire) (18).

Other reasons for sensory sensitivity in the five studies were related to 'the mixing of foods', which was common both among those with autism spectrum disorders and the control individuals (45 % versus 26 %). The question 'does the child avoid the taste and smell of certain types of food' clearly distinguished between the groups. This was rarely reported among the control individuals (5 %), while it was present in nearly half of those with autism spectrum disorders (49 %).

A large study (n = 1 462 with autism spectrum disorders, 70 % IQ > 80) showed that restricted food preferences was the most common trait (88 %) (13). This was followed by sensitivity to texture (47 %), but more niche phenomena also occurred, like eating only one brand of particular foods (31 %), hiding food in the mouth without swallowing (20 %) and an urge to eat non-digestible substances (pica). One weakness of this study was that only five questions about food selectivity were included and that no questions were asked about sensitivity to smell and taste.

A study of children with autism spectrum disorders from 2024 found that those who also had avoidant restrictive food intake disorder had significantly higher sensory sensitivity (visual, auditive, tactile and oral) than those who did not (22).

It proved challenging to find studies that only examined children with an intellectual ability level in the normal range. As this reduced the number of studies included, our confidence in these findings were rated as moderate.

Intellectual ability level

In general, food selectivity does not appear to be explained by intellectual ability level (13, 14, 17, 19, 20, 23). Intellectual ability levels were found to be equally good in children with autism spectrum disorders whether they displayed food selectivity (n = 784) or not (n = 328) (IQ 91 versus 92) (23). There was also no significant difference found when comparing the prevalence of food selectivity in those with an intellectual ability level in the normal range with those with an intellectual ability level below the normal range, neither in a large study (n = 1 443) (13) nor in a smaller study (n = 50) (17). Yet there was one exception: One study (n = 74) found that a group with autism spectrum disorders and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder had a significantly lower average intellectual ability level (IQ = 80) than those with autism spectrum disorders without this food intake disorder (IQ = 100) (22). Another study (n = 95) that used a multivariable regression model to examine factors that might explain food selectivity, found that intellectual ability level did not contribute significantly to the model (19). However, while some studies of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders with an intellectual ability level in the normal range reported small differences, there were significantly lower non-verbal intellectual ability levels reported for those with food selectivity compared to those without (14, 20). Despite the low number of studies, the consistency of the findings gave us a moderate level of confidence.

Autism symptoms

Out of seven studies that investigated the association between food selectivity and autism symptoms, four showed a higher symptom score for autism spectrum disorders for those with food selectivity, measured using a standardised survey instrument (11, 20, 23, 24), and one for those with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (22). The largest of the studies (11) described a particular association between these and stereotypical and repetitive behaviours, which is a core symptom of autism spectrum disorders. A study of a large birth cohort also found an association between autism symptoms and food selectivity; the strongest correlation was between the symptom 'restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour' and the study's ARFID score (ρ = 0.30; 95 % confidence interval 0.28 to 0.32) (24). Another study that made use of diagnostic subgroups, showed no difference between food selectivity rates among those with childhood autism and the other subgroups of autism spectrum disorders, but the number of participants was low (n = 37) (19). We assessed our confidence in these findings as moderate, although we cannot exclude a certain association due to measurement overlap between autism symptoms (restricted repetitive patterns of behaviour and interests) and food selectivity.

Somatic consequences

Six studies discussed the somatic consequences of food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Obstipation occurred more frequently among those with food selectivity (11, 23, 25). Overweight and obesity were reported to be associated with food selectivity in a clinical study of 151 children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (2–18 years) (26), while this was not found in two smaller studies (20, 27). Three separate case studies of boys with Asperger syndrome (10, 14 and 17 years) described gingivitis, scurvy (28) and severe malnutrition as having developed as a consequence of food selectivity (29, 30). Given the low number and small size of these studies, our overall confidence in these findings was considered to be low.

Discussion

This review article has identified a total of 20 articles on the topics of prevalence, characteristics and consequences of food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range, i.e. the group of individuals who in Norway tend to be assessed by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. We found a high prevalence of food selectivity in this group. In several studies these eating patterns were associated with a high degree of sensory sensitivity, particularly sensitivity to the texture and taste of food.

Prevalence

The prevalence of food selectivity was consistently higher in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range than in the control individuals, and it was similar to the level that has been reported for the overall group of autism spectrum disorders (2). However, prevalence figures varied considerably between studies, which is in line with what has been previously reported in literature reviews (5, 6). In part, this may be due to the studies' age range and gender distribution.

The most uneven gender distribution was found in a sample of 18 participants of whom 16 were boys (27). The high proportion of boys in most of the studies can be explained by a higher prevalence of autism spectrum disorders among boys (4:1) (31). This limits the extent to which findings may be generalised to apply to girls. Furthermore, the studies measured food selectivity in different ways. While some used the strict ARFID criteria (11), others applied a broader definition of food selectivity (14), or they focused on specific issues (15). Nevertheless, the study that used the ARFID criteria found a high prevalence, as approximately one in five individuals with autism spectrum disorders met the criteria. Unfortunately, this study did not include a control group. However, the studies that did, found considerable variation in the prevalence of food selectivity among control individuals (5–33 %). This may reflect the lack of consensus associated with the use of survey instruments, as shown in Table 2.

Sensory sensitivity

In line with the review articles that did not distinguish between different intellectual ability levels in children with autism spectrum disorders (6–8), we found several studies that associated a high degree of sensory sensitivity with food selectivity, including among those with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range. Sensitivity to food textures and taste were particularly important causes of food selectivity. In several studies, only a certain proportion of participants had an intellectual ability above a certain level (e.g. 70 % IQ > 80 (13)), and this may have influenced the results. Two studies that exclusively included children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range, found that food selectivity was caused by sensitivity to textures (12, 15). One of them also reported that neophobia and hypersensitivity to taste played a part (15).

Intellectual ability level

The studies we found do not suggest that food selectivity can be explained by the intellectual ability level of children with autism spectrum disorders, possibly because there was little difference between the intellectual ability levels of the groups that were compared. Several also involved small group sizes, although one large study (n = 1 112) found that the level of intellectual ability was virtually the same among children with autism spectrum disorders whether or not they displayed food selectivity traits (23). Interestingly, two studies showed significantly lower non-verbal intellectual ability levels in those with food selectivity than in those without (14, 20). However, the differences were small, and it is important to be cautious when interpreting findings until further studies are available.

Autism symptoms

Several studies indicate that children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and food selectivity have more autism symptoms than those who have no such eating patterns (11, 20, 23, 24). The largest study (11) described a special association between these eating patterns and stereotypical and repetitive behaviours, which is a core symptom of autism spectrum disorders.

Somatic consequences

We found somatic consequences of food selectivity also among those with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range. Obstipation was the most common (11, 23, 25), but we also found overweight and obesity (26). Instances of severe malnutrition that gave somatic consequences, were described in some case studies (28–30).

Limitations

This study had several limitations. It proved to be difficult to include only studies on food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range. Nevertheless, all the studies that were included in this literature review involved, either exclusively or generally, participants who had an intellectual ability level in the normal range (table 2). There is therefore reason to assume that the findings are representative of children and adolescents who are examined for autism spectrum disorders by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

Similarly, several studies had a wide age range and included young children, even if they were in a minority as we requested a mean age no lower than six years. The ratings of confidence levels had to be based on discretion, and this invited interpretive caution. The studies that were identified through the literature search, varied considerably in respect of design, participants, measurements etc., and detailed information was frequently not specified. We cannot therefore rule out that we have failed to include some articles that may have been relevant. Furthermore, we included only articles published in English-language peer-reviewed journals and may have overlooked knowledge from conference presentations, books or material in other languages. There were few studies on the individual themes, which dictated a cautious approach to interpreting findings. Overall, these limitations emphasise the importance of further research on food selectivity in autism spectrum disorders.

Conclusion

The high prevalence of food selectivity in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and an intellectual ability level in the normal range demonstrates that it is important to survey diet and nutrition whenever autism spectrum disorders are diagnosed by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. Clinicians should not overlook food selectivity traits that can be interpreted as part of the autism symptoms. Instead, it is essential that they examine what it is that drives the eating patterns in each individual, such as sensory sensitivity. This knowledge may well be important to the treatment. Both cognitive behaviour therapy and a family/ parent-led approach to increasing food intake variation have proved to be effective in the treatment of food selectivity (6, 7). There is a need for standardised survey instruments designed to uncover food selectivity in clinical settings as well as in research. There is also a demand for longitudinal studies (7). Moreover, studies that can increase our understanding of the mechanisms behind food selectivity, are important, e.g. with a focus on sensory experiences.

We are grateful to specialist librarian Ellen Bjørnstad for her work on the literature searches. The article has been peer reviewed.

- 1.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases and related health problems (ICD-10). 10. utg. Geneve: World Health Organization, 1990.

- 2.

Sharp WG, Berry RC, McCracken C et al. Feeding problems and nutrient intake in children with autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis and comprehensive review of the literature. J Autism Dev Disord 2013; 43: 2159–73. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Marí-Bauset S, Zazpe I, Mari-Sanchis A et al. Food selectivity in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. J Child Neurol 2014; 29: 1554–61. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- 5.

Ledford JR, Gast DL. Feeding Problems in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2006; 21: 153–66. [CrossRef]

- 6.

Bourne L, Mandy W, Bryant-Waugh R. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and severe food selectivity in children and young people with autism: A scoping review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2022; 64: 691–700. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Baraskewich J, von Ranson KM, McCrimmon A et al. Feeding and eating problems in children and adolescents with autism: A scoping review. Autism 2021; 25: 1505–19. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Page SD, Souders MC, Kral TVE et al. Correlates of Feeding Difficulties Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. J Autism Dev Disord 2022; 52: 255–74. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Jónsdóttir SL, Saemundsen E, Antonsdottir IS et al. Children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder before or after the age of 6 years. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2011; 5: 175–84. [CrossRef]

- 10.

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64: 401–6. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Koomar T, Thomas TR, Pottschmidt NR et al. Estimating the Prevalence and Genetic Risk Mechanisms of ARFID in a Large Autism Cohort. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.668297. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Kazek B, Brzóska A, Paprocka J et al. Eating Behaviors of Children with Autism-Pilot Study, Part II. Nutrients 2021; 13: 3850. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Mayes SD, Zickgraf H. Atypical eating behaviors in children and adolescents with autism, ADHD, other disorders, and typical development. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2019; 64: 76–83. [CrossRef]

- 14.

Dominick KC, Davis NO, Lainhart J et al. Atypical behaviors in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment. Res Dev Disabil 2007; 28: 145–62. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Kuschner ES, Eisenberg IW, Orionzi B et al. A Preliminary Study of Self-Reported Food Selectivity in Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2015; 15-16: 53–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Bandini LG, Anderson SE, Curtin C et al. Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. J Pediatr 2010; 157: 259–64. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 17.

Valicenti-McDermott M, McVicar K, Rapin I et al. Frequency of gastrointestinal symptoms in children with autistic spectrum disorders and association with family history of autoimmune disease. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2006; 27 (Suppl 2): S128–36. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 18.

Hubbard KL, Anderson SE, Curtin C et al. A comparison of food refusal related to characteristics of food in children with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing children. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014; 114: 1981–7. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 19.

Nadon G, Feldman DE, Dunn W et al. Association of sensory processing and eating problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res Treat 2011; 2011. doi: 10.1155/2011/541926. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Postorino V, Sanges V, Giovagnoli G et al. Clinical differences in children with autism spectrum disorder with and without food selectivity. Appetite 2015; 92: 126–32. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 21.

Chistol LT, Bandini LG, Must A et al. Sensory Sensitivity and Food Selectivity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2018; 48: 583–91. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 22.

Calisan Kinter R, Ozbaran B, Inal Kaleli I et al. The Sensory Profiles, Eating Behaviors, and Quality of Life of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. Psychiatr Q 2024; 95: 85–106. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Zickgraf H, Mayes SD. Psychological, Health, and Demographic Correlates of Atypical Eating Behaviors in Children with Autism. J Dev Phys Disabil 2018; 31: 399–418. [CrossRef]

- 24.

van 't Hof M, Ester WA, Serdarevic F et al. The sex-specific association between autistic traits and eating behavior in childhood: An exploratory study in the general population. Appetite 2020; 147. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104519. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 25.

Harris HA, Micali N, Moll HA et al. The role of food selectivity in the association between child autistic traits and constipation. Int J Eat Disord 2021; 54: 981–5. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 26.

Kamal Nor N, Ghozali AH, Ismail J. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Associated Risk Factors. Front Pediatr 2019; 7: 38. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 27.

Bandini LG, Curtin C, Phillips S et al. Changes in Food Selectivity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2017; 47: 439–46. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 28.

Planerova A, Philip S, Elad S. Gingival bleeding in a patient with autism spectrum disorder: A key finding leading to a diagnosis of scurvy. Quintessence Int 2017; 48: 407–11. [PubMed]

- 29.

Roth MP, Williams KE, Paul CM. Treating Food and Liquid Refusal in an Adolescent With Asperger's Disorder. Clin Case Stud 2010; 9: 260–72. [CrossRef]

- 30.

Rajendram R, Psihogios M, Toulany A. Delayed diagnosis of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and autism spectrum disorder in a 14-year-old boy. Clin Case Rep 2021; 9. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4302. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 31.

Surén P, Havdahl A, Øyen AS et al. Diagnostisering av autismespekterforstyrrelser hos barn i Norge. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2019; 139. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.18.0960. [PubMed][CrossRef]